Cell division is one of the most basic and important biological processes of all living things, yet scientists still don’t fully understand the way it works or, sometimes, doesn’t work.

Here’s a quick refresher for those of us several years removed from biology class. In typical human cell division, chromosomes in a nucleus are replicated and lined up in the center of a cell. They are then pulled neatly apart and separated into halves at opposite sides of the cell. This is called chromosome segregation. The single parent cell divides into two identical daughter cells, each with 46 chromosomes.

If these chromosomes are somehow distributed incorrectly, this can lead to health issues like miscarriages, birth defects or the development of cancer.

This process is precisely what the Cell Cycle & Cancer Biology Research Program at Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF) hopes to untangle with the help of a $2.1 million grant recently awarded through the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS).

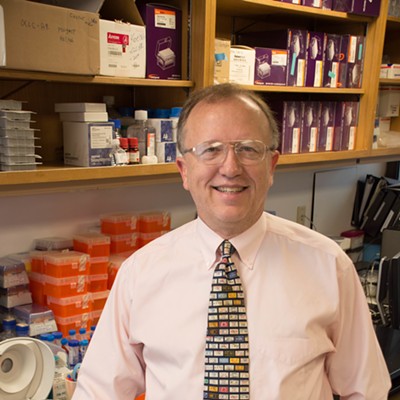

OMRF scientist Gary Gorbsky, Ph.D., leads the research effort. For Gorbsky, a childhood love of explorer Jacques Cousteau’s television show eventually grew into a passion for science, which led him to a career in cell biology. He joined OMRF as chair of the Cell Cycle & Cancer Biology Research Program in 2003.

His fascination with cellular systems drives much of his research.

“They’re incredibly intricate and complicated machines, a million times more complicated than anything that humans have made,” Gorbsky said. “They’re machines that can duplicate themselves.”

For years, he has advocated for comprehensive, fundamental exploration of cellular structure and function.

“Even from a practical point of view, most diseases are problems with cells, things that go wrong with cells,” he said. “We can’t really understand how to fix these problems until we learn how things normally work.”

A favorite analogy he often uses is a person taking their car to an auto mechanic who first must understand how the car works to be able to fix it. Similarly, scientists cannot hope to treat or correct problems in cells without knowing their basic functions.

“So that’s what I think is our goal,” he said, “trying to write the shop manual for how cells work. Particularly in my specific laboratory, we’re trying to figure out how they manage to do this process of separating their chromosomes when cells divide.”

Research freedom

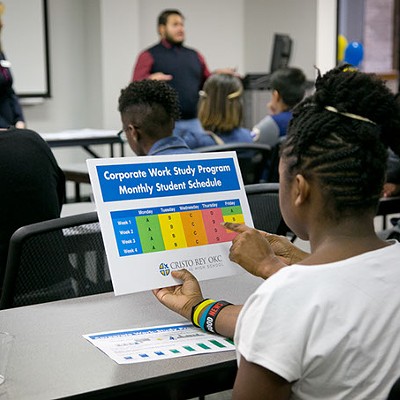

OMRF’s new grant is a Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award (MIRA), a unique funding source that allows for broader, freer research opportunities over a period of five years. It is not designed around a specific project, but around a laboratory or a principle investigator. OMRF scientists will be able to explore many ideas within their approved research program rather than being limited to searching for exact results.

Gorbsky and his lab team are thrilled about the freedom the MIRA grant affords.

“What is nice about it is that you’re not restricted to a project, so you can follow the exciting results where they lead you,” he said.

He paraphrased Jon R. Lorsch, Ph.D., the director of NIGMS, who shares Gorbsky’s research philosophy.

“If you know exactly what experiments you’re going to be doing five years from now, you’re not a very creative scientist,” he said with a laugh.

The research in Gorbsky’s lab will further the science not only within their team at OMRF, but also within the wider field of cell biology. He called the scientific endeavor a group activity.

His team will study the point of cell division when the chromosomes duplicate, move to the middle of the cell and separate at the same time. Gorbsky’s lab will focus on the “checkpoint system” that makes sure all the chromosome pairs are in the right place at the right time before they’re pulled apart. He joked that they all have to huddle at “the 50-yard line” for division to happen.

They will also examine “cohesion fatigue,” an anomaly Gorbsky’s lab first discovered in 2013. Basically, in cohesion fatigue, chromosomes stay at the figurative 50-yard line too long and they can be pulled apart haphazardly. They can get broken or wander around the cell at random.

“We think that cohesion fatigue could contribute to this notion of how, for instance, cancer cells get the wrong number of chromosomes,” Gorbsky said.

Cancer is linked to cell division gone bad. According to Gorbsky, cancer cells often have more than 46 chromosomes and also tend to have broken chromosomes. He explained that cancer cells can get addicted to certain biochemical pathways, which his lab will work to identify. This research will be beneficial in the field of precision medicine.

“If we could, for instance, find a pathway that is not essential in the normal cells but is essential in a particular cancer cell, then you could perhaps target that specific pathway for that particular tumor,” Gorbsky said.

Cell division and chromosome missegregation are also relevant in the study of birth defects and miscarriages. For example, in the case of Down syndrome, an extra chromosome 21 is present in cells. Gorbsky’s lab wants to find the “inducers” of missegregation to prevent cellular abnormalities from occurring.

More than anything, Gorbsky emphasized basic research, which helps the study of science as a whole and can lead to breakthroughs even years later.

“That’s what drives us,” he said. “Exploring new worlds and seeing things that no one’s ever seen before. That’s what really lights up a scientist.”

Visit omrf.org.