The Jurassic Games

Take the dystopian, gladiatorial reality-show aspect of The Hunger Games series and drop in some of Jurassic Park’s classic scaly predators and you have the basic premise for The Jurassic Games, the latest popcorn-shoveling sci-fi action flick from director Ryan Bellgardt.

The man behind past fan favorites Gremlin and Army of Frankensteins has crafted his own creature-feature niche at deadCenter Film Festival. The Jurassic Games does more than live up to those titles, channeling two widely cherished major film franchises at once.

Fans won’t find Jennifer Lawrence or Chris Pratt in this ambitious mashup, but strong acting performances can be found throughout The Jurassic Games’ cast. The story follows death-row inmate Anthony Tucker (played by actor Adam Hampton), who is accused of murdering his wife. Instead of straightforward execution, he is given the chance to compete in a hugely popular television reality competition that puts death row inmates on a computer-simulated island, where they must achieve a series of tasks while surviving attacks from the island’s dinosaur residents (and, of course, their murderous co-stars). The last standing survivor earns freedom and criminal exoneration.

Tucker, who maintains his innocence, accepts the show spot in hopes that he might win and be reunited with his children, who are certain their father is no murderer.

The Jurassic Games does not spend much time explaining how the world has come to such a chaotic state that such a bizarre and ill-advised show would be allowed to exist, and that is a good thing. Fictional dystopias are frequently bogged down with setup and backstory. Bellgardt doesn’t ask his audience to do anything more than accept the story’s core scenario.

Many of Tucker’s competitors are specialists in nasty, antisocial behavior. Convicted killer Joy (Katie Burgess) is as unpredictable as she is violent, but some others have redeemable qualities, like martial artist Ren (Tiger Sheu), who engages in the ever-rare kung-fu battle with three velociraptors. Guiding everything along is the show’s polished host (Final Destination 3’s Ryan Merriman), who has an unhealthy obsession with churning TV drama out of human suffering.

The Jurassic Games should go down as Bellgardt’s best work to date. The visual effects are phenomenal considering the film’s miniscule budget — at least compared to the blockbuster franchises that inspired it. It’s classic summer fun the whole family can enjoy. — Ben Luschen

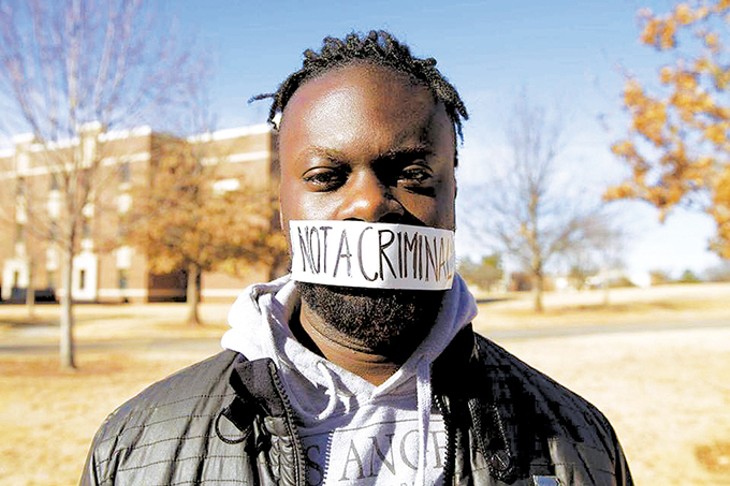

You People

First-time director Laron Chapman mixes in comedy to make important subject matter more approachable and makes a $40,000 budget seem larger for his passion project, You People.

Chapman, who also wrote the script, taps into issues of identity surrounding race, gender and sexuality by using his own experience as a biracial gay man living in Oklahoma City through the character of Chad Johnson (played by Joseph Lee Anderson), a black man adopted by a suburban white family.

The film opens with Johnson leaving a class assignment blank when asked to identify himself and a montage of images such a Black Lives Matter demonstrations and pictures from Oklahoma City’s Pride parade, but the film immediately takes a comedic turn with laughs presented by Johnson’s adoptive parents (Michael Gibbons and Cindy Hanska).

The mixture of comedy and identity issues can be cringe-worthy at first, especially when Chad’s white best friend Michael (James Austin Kerr) tells Johnson they need to “revoke his black card” and calls himself the “Mr. Miyagi of Blackness” while using the n-word, but that is Chapman’s intent.

Many of Chad and Michael’s interactions are based on Chapman’s real-life experiences and prepare viewers for intense scenes later in the film.

Johnson’s worldview begins to change when he’s introduced to love interest Melanie Fischer (Gabrielle Reyes), as he is worried he “isn’t black enough for her.”

“You’re black because you’re born black. It doesn’t come with an instruction manual; just be yourself,” Fischer tells Johnson.

His relationship with Fischer unfolds as his birth mother Jasmine Jones (played with an excellent turn by Vanessa Harris) enters his life for the first time.

The film is aesthetically appealing and looks better than its budget might indicate. The most riveting scene in the film comes as Johnson is pulled over by a law enforcement officer late at night, and the flashing lights dance in the background like flames on a fire.

Chapman shows much promise in his first feature, proving capable of balancing comedic and dramatic beats throughout the film. — Jacob Threadgill

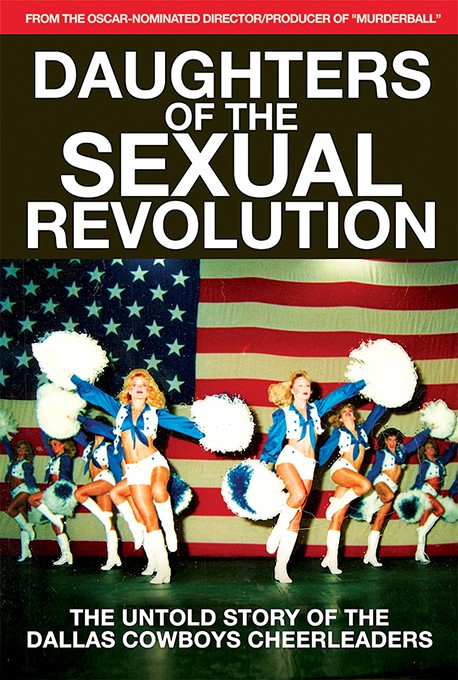

Daughters of the Sexual Revolution: The Untold Story of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders

Inspiration can come in many guises. According to legend, the genesis of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders stemmed from a 1967 football game at the Cotton Bowl when Cowboys general manager Tex Schramm spotted a local exotic dancer, Bubbles Cash, as she made her way down a staircase while in a miniskirt and holding two spindles of cotton candy as if they were pompoms. An idea struck Schramm. Several years later, the Cowboys introduced its new cheer squad of scantily clad, buxom young women. The documentary Daughters of the Sexual Revolution: The Untold Story of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders chronicles how the original DCC became iconic of the freewheeling 1970s and early ’80s, bringing the allure of sex to the seemingly non-erotic world of NFL football.

Documentary maker Dana Adam Shapiro, in his first work since 2005’s excellent Murderball, details the cheerleaders’ ascent through terrific archival footage and a host of interviews with various ex-DCC members and other principals. One of those interviewees, former Cowboys Cheerleaders director Suzanne Mitchell, emerges as a key force in transforming the squad into a pop culture bonanza.

Decked out in knotted half-shirts, short shorts and white vinyl go-go boots, Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders inhabited a space where America’s social landscape was being shaped by both the women’s liberation movement and the sexual revolution. Mitchell, the only female executive in the Cowboys front office, presumably would have been a champion for feminism, but the DCC were also derided as midriff-baring pawns of a leering patriarchy. “A lot of women didn’t like us,” recalls one ex-cheerleader. Love ’em or hate ’em, the Dallas cheerleaders were an unequivocal phenomenon. The proverbial dam broke in 1976 during Super Bowl X. A TV cameraman, cutting away from the Cowboys-Steelers matchup, captured the knowing wink of a Dallas cheerleader. “After the wink,” recalls a former Cowboys broadcaster, “all hell broke loose.”

It wasn’t long before the DCC were appearing in everything from posters and calendars to appearances on TV’s The Love Boat and Family Feud. The mega-celebrity obscured the fact that squad members were subject to strict rules governing life off the field, all for a meager $15 per game (before taxes).

Despite some chatter paid to the American heartland’s curious intersection of religion and sex, Daughters of the Sexual Revolution is unsurprisingly (perhaps fittingly) skin-deep. But with its quick edits, brisk pace and visual wit, the documentary is fun and consistently entertaining. — Phil Bacharach

The World Before Your Feet

In 2010, Matt Green relinquished his engineering career, opting instead to walk 3,000 miles from New York to Oregon. Finishing his countrywide stroll still left a hunger in his shoes, as subsequently, Green resolved to cover every street of New York City’s five boroughs. A chronicle of Green’s urban journey, Jeremy Workman’s The World Before Your Feet is an intimate panorama of humanity shot through Green’s exhaustive experiment.

Green, and by extension Workman, discards any needless injection of grandeur at the film’s onset. Green muses at the monetization of his quest before shrugging the notion off and walking on. Far more concerned with moments and history, the film is an endearing collection of beautiful vignettes. While some of the work’s movements concern themselves with mortality and nationalism, others entail the city’s local color and microscopic nuances. Omitting so much as a recognizable glance of Times Square, Green and Workman capture the city’s complexity beneath its popular veneer.

Illuminating the subtlety and depth of everyday interactions, the frame maintains a second-person perspective. Green facilitates conversations without forcing a trajectory, yielding a natural dialogue absent from many similar documentaries. The film’s catalogue of information is eclectic yet accessible, and Green’s discussions bound between the machinations of modern New York and musings on Americana.

Green’s disregard for a “purpose” within his work is troubling, and a white man roaming New York fawning over architecture and other civil quirks can feel a bit superficial. Workman proves he is not oblivious to this notion — through an encounter with Garnette Cadogan, a fellow walker and commentator, Workman puts a sincere effort into capturing the actual composition of New York rather than some pristine, white fantasy.

Gradually, the film considers the biographical implication of Green’s journey. The amount of life he encounters often leaves him wondering if his endeavor will ever conclude; the city is a cyclone of narrative “layers,” as Cadogan suggests, changing faster than Green could ever walk. Eventually, the cause for the trek itself becomes far less interesting than Green’s compulsion. The World Before Your Feet’s reflection on urban life is a pleasant reprieve from the frequent severity of contemporary documentaries. — Daniel Bokemper

A Shot in the Dark

Anthony Ferraro is an impressive young athlete: driven, tenacious, eager to learn, and blind. The 17-year-old New Jerseyite is the focus of A Shot in the Dark, a documentary that details Ferraro’s senior year in high school as he seeks to win district, regional and state tournaments.

You get the impression that director Chris Suchorsky (he also produced the picture with Ferraro’s older brother, Oliver) had set out to make a feel-good sports story, and certainly Anthony is worthy of inspiration. But like the most successful documentaries, A Shot in the Dark stumbles into more interesting stuff when real life strays from the assumed narrative.

For the most part, the film is conventional storytelling to a fault, a perfunctory mix of interviews, wrestling action and scenic shots of the Jersey shore. But the movie does not flinch from ugly tones. Because his disability means that opponents must maintain touch-contact with him throughout a match, it leads to plenty of grousing from competitors, both on the mat and in the bleachers, that Ferraro exploits his blindness for a competitive edge. Hey, don’t forget this is Jersey. “People that are hating on him because of the way he has to wrestle, that’s hard for him to deal with,” says his wrestling club coach, Mike Malinconico. “That bugs the shit out of him, and it should. He’s been dealing with the haters of the world since he started.”

There’s no ambiguity where the filmmakers stand on the issue. When a spectator complains that Ferraro has an unfair advantage, the hater is identified as “random douche” in a caption at the bottom of the screen. Ferraro is not the stoic type. The constant taunts spur the young man’s periodic lapses into self-recrimination and self-pity. High school coach Pat Smith muses that Ferraro has a “big emotional disadvantage” because his lack of sight compels him to pay too much attention to what he overhears.

If only the documentary had more fully explored Ferraro’s unguarded moments. Music cues hammer what viewers are supposed to feel. And some of the interviews are terrific — Malinconico deserves a spot in the next Kevin Smith movie — there is also a fair amount of filler. We probably don’t need Ferraro’s fellow wrestlers to explain how it sucks to lose, and references to Hurricane Sandy and a blizzard flit by without context. A Shot in the Dark earns a takedown but could have gone for a fall. — Phil Bacharach

Purple Dreams

In 2015, drama instructor Corey Mitchell won the first Tony Award for excellence in theater education. Acclaimed for his efforts to challenge and strengthen students through his productions, Mitchell achieved national recognition for his adaptation of Alice Walker’s The Color Purple. Joanne Hock’s Purple Dreams traces the trials of Mitchell’s endeavor, focusing on individual dilemmas and mold-breaking behavior of students at Northwest School of the Arts in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Purple Dreams covers the weeks prior to the musical’s first public performance. At-risk students populate the production’s ensemble, and the film often captures the blight and decay of urban North Carolina, but Hock hones in on the teens’ resolve to fight society’s presumptions.

The filmmaker’s intuition is on point; the stories cover a broad topical spectrum. One thread follows Brittany, an 18-year-old on the cusp of being forced out of the curriculum. Despite her stuttering academic performance, The Color Purple instills a sense of empowerment within Brittany, pushing her toward a collegiate trajectory she never thought possible. Hock promotes the power of the arts throughout her documentary, illuminating opportunities without hindering Purple Dreams’ flow.

Unfortunately, everything beyond the film’s first hour feels rushed, almost as if the students’ tales end after their first successful production. Hock’s examination becomes glossed and almost seems truncated by its conclusion. Though the film would likely do well to not push the length of something like Hoop Dreams, it seems an additional 20 minutes might have allowed the piece to fully actualize.

Perhaps propelled heavily by Mitchell, Hock’s comedic timing is exceptional and her humor is refreshing without compromising moments of sincerity. Hock’s ability to convey triumph over consequences is masterful and would readily translate to a narrative feature.

Purple Dreams is a testament to the power of theater and a champion of creativity. Despite peculiar pacing near the film’s end, it maintains a sense of gravity and importance throughout, and Hock displays a knack for harnessing emotion through precise storytelling. — Daniel Bokemper