Andrew Ivy / DCF Concerts / provided

Promoters at Diamond Ballroom in eastern Oklahoma City were among the first to join National Independent Venue Association, which is working to compel lawmakers to act and pass industry-saving legislation. (pg 24, 25)

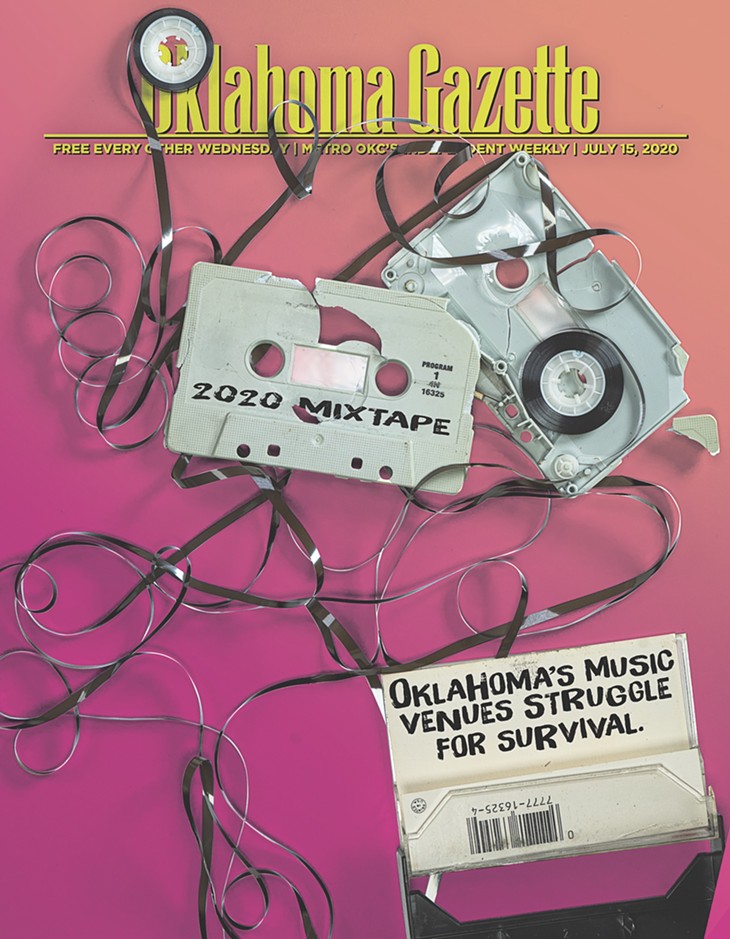

For music lovers, the pandemic is a bummer. For many independent venues, it will be their demise. With their primary source of revenue eliminated, venue owners have had no choice but to furlough or terminate their staff. Venues that qualified for EIDLs (Economic Injury Disaster Loans), PPP (Paycheck Protection Program) and state-backed OBRP (Oklahoma Business Relief Program) only received a momentary lifeline, if any at all.

Acclimating to the pandemic has been nearly impossible for most venues. Chad Whitehead, the in-house talent buyer and operating partner of Tower Theatre and Ponyboy, found live music has adjusted in “the way a car crash acclimates after an accident comes to a stop.” What is known is that the circumstances are severe and the solutions are sparse.

“We did temperature checks at the door, but with so many asymptomatic cases, it’s hard to know if someone has it. We’re a petri dish for something like this,” Nick Hampson, owner of 89th Street - OKC, said after his venue reopened and closed again after a spike of cases in late June.

Without a downward trajectory of cases, most venues do not have the means to safely present shows. Preventive measures, such as a minimum of six feet between occupants, can cut a venue like Tower’s attendance and revenue by nearly 80 percent. These projections are not promising for a business that routinely assumes a significant financial risk.

“We have to go find some way to get a piece of regular business and acclimate to that, but it’s like breathing through a straw,” Whitehead said. “I don’t know how you acclimate to something unsustainable. Every venue in the world has to figure out how to stretch their oxygen to survive this.”

The pandemic presents an unexpected roadblock to touring musicians as well. Even if a stage was in a relatively low-risk area, artists can put themselves and their audience in danger bounding from one city to the next. Chad Rodgers, manager of Cain’s Ballroom alongside his brother Hunter, broke down the scenario.

“We came to the realization even if we could do a show, would the artist show up? Why would they travel on a tour bus crammed with a dozen people to one city that turns out to be a hotspot like Tulsa and then to another?” he asked. “They could end up spreading it themselves.”

Hybrid venues like The Jones Assembly have an option to adapt in the absence of large-scale concerts. Still, with the day-of cancellation of Orville Peck’s sold-out performance and countless other anticipated shows, the blow to their business is staggering. Graham Colton, co-owner of The Jones, felt its restaurant operation “allowed us to pivot and be flexible and reopen,” but that the loss of its “third tier” of business is “unimaginable.”

Making music

Despite their plight, many venues have found some outlet to keep their mission alive. The Tower produced a series of livestream performances from Ponyboy shortly after it closed, with the intent to resume those performances later this summer. The Jones has allowed local musicians to perform at a distance on its outdoor patio Tuesdays through Fridays. Cain’s and 89th Street have found success through merchandise sales and fundraisers for their staff, with the former preparing to roll out a new series of merch later this year. However, livestreams are far from profitable, and merchandise sales are a minimal, temporary solution to long-term predicament.Unfortunately, the majority of independent venues will not reopen without meaningful federal assistance. The death of these venues will, in turn, have an irreparable impact on their local economy. Jamie Fitzgerald, veteran promoter and co-owner of DCF Concerts, elaborated on the domino effect this loss of industry spurred.

“For every dollar spent on a ticket at a small venue, a total of $12.00 in economic activity is generated within our community on staffing, restaurants, hotels, travel, transportation and retail establishments,” she said.

Despite the size of the venues DCF represents, ranging from Diamond Ballroom to BOK Center, its revenue has been reduced to $0 as of March 14. The national talent-buying venture Whitehead contributes to, Patchwork Presents, was forced to suspend the majority of its operations. On the operational end of the spectrum, Fitzgerald explained that over 75 percent of the support staff involved in the industry are jobless, with the other percentage working with reduced pay.

March 6, Michael Trepagnier opened his recording studio, Cardinal Song. Though Cardinal’s first months of operation were a stress-inducing “vacuum,” May and June brought promise with a consistent wave of bookings. Fortunately, the compulsion to create music is alive and well.

“People just need music,” Trepagnier said. “They’re starved for it. Artists need to get in, create it, and put it into people’s hands in order to remain relevant and express themselves.”

Time away from the live stage has forced artists and producers alike to contemplate distribution. At the very least, it has given them the opportunity to hone their craft.

“This time will empower people at home to record even more, so when they get into a studio, they will be more efficient and organized at making music,” Trepagnier said.

Saving venues

As venues begin the journey of reopening, safety measures will likely encourage new streams of revenue and accessibility. Tower, for instance, is considering the prospect of a virtual ticket. Trepagnier theorized that because most large acts already mix video as a part of their sets, transmuting that process for a remote audience seems inherent.Unfortunately, a venue that does not exist will not be around to reap the benefits of such an option. National Independent Venue Association (NIVA) was founded at the onset of the pandemic by Dayna Frank, an independent promoter from Minneapolis, with the goal of compelling lawmakers to act and pass industry-saving legislation. DCF and the venues they represent were among the first of approximately 2,000 businesses to join the cause.

“We have to fight for our livelihoods and save the small concert stages that have shined a light on every superstar in the world,” Fitzgerald said. “These 200 to 3,000 capacity clubs and theaters are stepping stones to every huge commercial artist that plays arenas and stadiums. Unlike city and state-owned facilities, many will never reopen again without federal assistance throughout 2020 and 2021.”

Without a government solution, Whitehead figures at least half of the independent venues nationwide will not reopen. This could be cataclysmic for the health of the community.

“That might not sound like a big deal if you don’t go to concerts, but live cultural entertainment accounts for 4.5 percent of Oklahoma’s economy,” he said. “Boeing is 5 percent of the economy, so it’s almost a Boeing-level industry that is being impacted with very little support from the government.”

The road for venues, promoters and musicians alike will feel, and in many cases be, insurmountable. There is an increasing fear that the collapse of small venues will lead to mass assimilation of stages by massive conglomerates like Live Nation, obliterating some of the crucial platforms for smaller artists looking to make a name for themselves.

Colton finds that one of the few solaces of this time is that music is inevitable. Just because an audience is not shouting for them, that does not mean it disappeared.

“Let the artists know, regardless of their size, that you’re thinking about them,” he said. “Ask how you can support their music. Yes, we’re missing the direct connection with the live music part of it, but certainly those artists are still creating, and we still need to be there for it.”

For more information on NIVA’s mission to rescue venues, visit saveourstages.com.