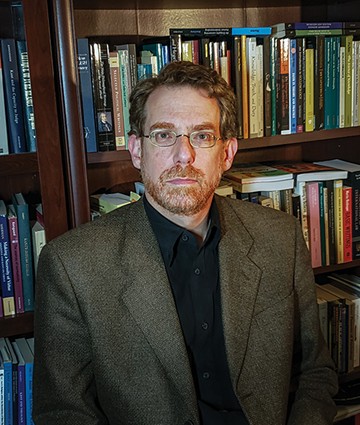

Lawrence Pasternack approaches his cannabis activism as a moral imperative.

Pasternack is a professor of philosophy and the director of religious studies at Oklahoma State University. While he has supported cannabis legalization for decades, it was not until 2017 that he began writing and speaking publicly on the matter.

“I grew up in Canada, where marijuana use was just never that big of a deal in the way that it has been in United States with the massive war on drugs,” Pasternack said. “While it was illegal in Canada for most the time I was growing up, it was not something that really mattered to people. It was not really a major social concern and was legalized for medical use more than twenty years ago. I never really had any interest in it. I just like having a clear head. It's not something that I was particularly drawn to, but in terms of my own personal worldview, I've always thought that the war on drugs is egregiously bad. It's an awful public policy. It’s basically a war of the government against its own people, the government having control over our bodies, denying own personal and medical autonomy. It’s a profound violation of what we think liberty is supposed to be because if you can't have liberty over your own mind, what liberty do you really have? Drugs, like anything else, could be used for good or ill, but drugs can provide people with a means to alter their mental state, which allows them to explore other ways of thinking and being.”

“I was blown away because people say

tweet this

there’s no research. That’s not true.”

—Lawrence Pasternak

Pasternack received his bachelor's degree from York University and earned his master’s degree from Yale University before going on to complete his doctoral work at Boston University. He publishes a large amount of academic work each year. His inquisitive nature led to him to delve into the academic literature surrounding medical applications of cannabis.

“I have scoliosis, and I'm in constant pain from it,” he said. “I finally got to a point where it was just getting to be too much for me, so I needed something to step away from my desk, and I became aware of the state’s medical marijuana movement. Initially, I didn't know anything about medical marijuana. I knew that people made the claim that it had such benefits, but I never read anything about it. So I actually started to read.”

From sociological and medical studies to epidemiological data, Pasternack read hundreds of articles.

“I was blown away because people say there's no research. That's not true,” he said. “There's around 40,000 publications, and so I just went from one to another to another to another. I started to send emails to cannabis researchers, and I began to get a much more complete picture of the medical benefits.”

His research eventually prompted him to reach out to activists like Norma Sapp and Frank Grove, offering to organize talks and debates and donating to the local cannabis legalization movement. This led to Pasternack writing editorials when the pain did not allow him to work the long periods he was used to.

“It was just getting harder and harder for me to spend the ten to fourteen hours a day, seven days a week that I'm used to writing. And I just started to write these op-eds because I could write an op-ed when the pain was too much to do any serious academic writing that day,” Pasternack said.

His editorials have now appeared in The Oklahoman, The Journal Record and Tulsa World, among other publications.

Affecting policy

Those editorials led to Tom Bates, the former commissioner for Oklahoma State Department of Health, reaching out to Pasternack just after the passage of State Question 788 when the department had announced the ban of flower.“Basically the sense of that meeting was they just felt lost,” Pasternack said. “They were getting so many people telling them so many different things that they didn’t know who to believe. So I think they saw me as a fair broker, an honest broker, of information. They wanted to know what's true. What does it really mean when a state legalizes marijuana? What really happens?”

A bit of misinformation had led the board to want to prohibit the sale of cannabis flower.

“Someone was telling them all this, for example: Two people are walking down the street. One guy lights up a joint. The next guy is downwind. The wind blows the marijuana smoke over to the next guy, and he gets stoned as well,” Pasternack said. “So the board of health was being told that if you don't ban flower, everybody around on the street when people are smoking are going to get high as well.”

Pasternack provided Bates with a 2015 Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine study to set the record straight. The study showed that even with seven people smoking marijuana beside one not smoking in an enclosed room, the nonsmoker doesn’t get high or have a detectable level of THC.

Despite now becoming one of the most recognizable activists in the medical cannabis sphere in the state, Pasternack still does not feel comfortable enough to use cannabis.

“If and when the federal law changes, then that will have a cascading effect. That will make me far more comfortable,” he said.

In the meantime, he will continue to write editorials about various facets of its medical application, work with legislators and activists and promote patient interests.

“We philosophers complain about how bad public policy is and how little reason, how little data is used in forming these policies. Well, guess what. We philosophers can do something about it. We have the skill set to do something about it. So let this be a call to arms. Let there be an army of philosophers out there who go down to their state capitals, like I have, and say, ‘Here's the data. You need good policy that reflects the data,’” Pasternack said. “When we're talking about something like cannabis or other banned substances that are safer than many pharmaceuticals, it's completely inappropriate. These bans from the start were never based upon medical or sociological research. … That it remains illegal at the federal level while nearly 50 other countries have legalized it for at least medical use is a testament to how far this country is from being the beacon of liberty it claims to be. My need to fight against bigotry and promote rational public policy has found expression in the 788 movement.”