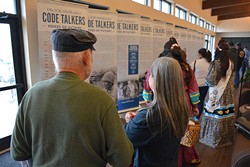

During World War I and II, Native Americans used their languages as codes to help the United States win. Now, an exhibit honoring those men is on display through November at Cherokee Nation Veterans Center in Tahlequah.

Oklahoma Native Americans have the distinction of being the first American code talkers used in war, said Director of the Office of American Indian Culture and Preservation William Welge.

“The use of their language to send messages, orders, etcetera for combat purposes was employed by Indians speaking the same language,” said Welge. “Their C.O. [commanding officer] saw that it would be advantageous, as the Germans had no idea what they were saying.”

However, the two world wars are not the first instances of Native languages being used by the military. Travis Owens, the manager of cultural tourism for the Cherokee Nation, said the benefits of using Native languages during war have been employed since the beginning of European occupation in North America.

“This continued through to World War I, when the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, Choctaws, Cherokees and several other tribes were tasked with using their language for official capacities,” Owens said. “In those times, the native code talkers had to send sensitive messages, but they had no formal code written in their language. Using native languages in an organized, code-based form did not start until the Second World War.”

The exhibit highlights Cherokees, Choctaws, Comanches, Navajos and other tribesmen who served as code talkers.

“We do feel it is our responsibility to really highlight the contributions Cherokees made to code talking in the war and to honor their memories, “ Owens said.

The first known messages transmitted under fire were by a group of Cherokee troops that served alongside the British at the Second Battle of the Somme in September 1918.

Nobody is sure how many lives were saved due to the code talkers’ efforts. However, historians do not dispute that the United States and many other countries benefited greatly from the code talkers’ ability to speak their native languages.

“Knowing where your enemy was, where his supplies were located and how you could get the upper hand was life or death during war. But when Native Americans began to speak on tapped wire systems in their aboriginal languages, many of which were not written down, they created an unbreakable code,” Owens said.

Owens admits that the outcome of the wars might not have changed without the service of native soldiers, particularly the code talkers. But he said it cannot be denied that their contributions saved thousands of lives and were a big factor in the allied victories.

Despite Native Americans being subjected to cultural eradication in Indian boarding schools during the late 1800s and early 1900s, they still used their culture to save American lives and interests. However, several factors played into their desire to serve in the U.S. military.

At the time of WWI, Native Americans were still not considered citizens, so part of the reason some joined the armed forces was to gain full citizenship. Congress then passed the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, and by the time WWII took place, Native Americans enlisted at a higher rate than all other U.S. citizens.

It was during the Great Depression, and many joined because the military offered free room, board, clothing, food and pay to enlisted soldiers. It provided a job and a place to live while also providing the ability to send money home to families.

“Serving in the military came naturally to many natives,” Owens said. “Unlike their counterparts, they had already completed several years of military-style discipline while attending government-run boarding schools as children.”

Native traditional ideology also taught them to not complain during minor discomfort, Owens said. During war, it was not uncommon for Native recruits to share their culture, particularly song and dance, with their fellow soldiers to help boost morale.

“While it’s not to say Natives did not suffer mistreatment by the U.S. government, a resounding number are proud to have served their country and their tribal nation in defending them,” Owens said.

Since the code talker programs were kept secret by the military for many years, identifying those who served as code talkers is difficult. The information is just now being declassified and released to help historians identify who was involved in this practice.

Joseph Oklahombi is one of the better-known Native soldiers from Oklahoma. He served during World War I as a Choctaw code talker, becoming the most decorated solider from Oklahoma during WWI. Oklahombi was tragically killed in 1960 while walking along a road.

Other known code talkers from Oklahoma include Forrest Kassanavoid, Charles Chibitty and Haddon Codynah, who were Comanche code talkers in WWII. Chibitty was the last of the Comanche code talkers when he died in 2005. Chibitty means “holding on good,” and he was also the last hereditary chief of the Comanches, having descended from Chief Ten Bears, who was one of the signers of the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867, according to Chibitty’s obituary in The Washington Post.

In 2013, only 40 to 70 code talkers were estimated to be living. The number is still unknown due to the information being classified.

“This makes it difficult to track down stories of code talkers and to share them,” Owens said, “However, we do know there are no living Cherokee code talkers.”

The last recorded time of code talking used in war is also unknown. There is a possibility that it was used during the Korean War, Welge said.

Despite not knowing all the stories of code talkers, historians are still gathering information as the U.S. government slowly declassifies records.

Print headline: Tribal code, Native Americans are honored for their roles as code talkers in the American armed forces.