Standing in a circle of students outside his middle school, 13-year-old Ruben Avila looked at the bleeding face of a student he just cut and then at the knife in his hand.

“I couldn’t believe that it was me who did that,” he said. “[I thought about running away,] but I was just in shock because of what I did.”

It was the gory outcome of many hard days at Roosevelt Middle School in the Oklahoma City Public Schools (OKCPS) district, where Avila struggled with bullying and gang tensions.

“Where does the school-to-prison pipeline start? It starts right there,” said OKCPS Superintendent Rob Neu.

He could have turned out like some students who get lost in large schools; he could be sitting in prison.

But he is not. Instead, he was given probation. He was expelled from OKCPS but found Justice Alma Wilson SeeWorth Academy, an alternative school where he could more meaningfully connect with staff and peers. His fiercely loving mother continues to be his anchor. The beginning of Avila’s story is common, but the positive end is not.

The pipeline

Across the city and the nation, students of color, especially African-American students, are suspended at disproportionately high rates.

Since the late 1980s, the U.S. has seen dramatic increases in suspensions of low-income students and students of color. This trend is often called the “school-to-prison pipeline,” as youths are increasingly shunted from public schools into the juvenile justice system, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

Oklahoma’s numbers, especially Oklahoma City’s, have mirrored or led national trends.

Neu was blunt about the district’s past involvement in contributing to the school-to-prison pipeline.

“To me, it’s disengaged kids, bored kids, stressed-out staff, teaching to a test. Then the kids act out because they don’t get it, or they’re not keeping pace with everyone else,” Neu said. “And that’s where we really screwed up the system. Then, once they started down the suspension road, they’re in the pipeline.”

A 2015 report by the UCLA Center for Civil Rights Remedies, Are We Closing the School Discipline Gap?, went in-depth on suspension rates by state and nationally, using U.S. Department of Education data from school districts for the 2011-2012 school year, the most recent available.

The numbers were revealing.

“Given that the average suspension is conservatively put at 3.5 days, we estimate that U.S. public school children lost nearly 18 million days of instruction in just one school year because of exclusionary discipline,” read the report summary.

Among suspensions of high school students nationwide, almost 7 percent were white, around 23 percent were black, almost 12 percent were American Indian and nearly 11 percent were Latino, the report shows.

That year, OKCPS ranked worst (No. 1) nationally for its abnormally high suspension rate of black students, which topped 64 percent (75 percent of which were male). Fifty-one percent of Native American OKCPS high-school students were suspended (60 percent of those were male).

The deep disparities in Oklahoma’s prison populations closely resemble the trends of suspension rates.

Using 2010 Census data, Prison Policy Initiative, an incarceration reform think-tank, published numbers for Oklahoma’s prison population.

While African-Americans comprised 7 percent of Oklahoma’s overall population, they represented 26 percent of the incarcerated population. Hispanics were 9 percent of the state’s population and 15 percent of incarcerations.

By comparison, whites comprised 69 percent of Oklahoma’s population and 49 percent of the incarcerated population.

In public schools, many, including Neu, challenge the effectiveness of exclusionary discipline. Neu is working to help fill the nonacademic needs of at-risk and low-income students while keeping them engaged in learning.

Alternative schools provide more comprehensive student care than ever before in American education.

Outcomes

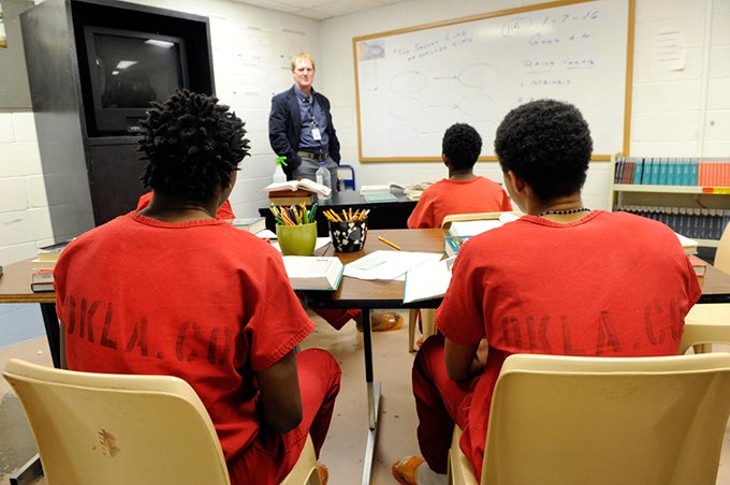

Todd Mihalcik sees the eventual extreme outcomes of student discipline. He’s the OKCPS teacher contracted by the Oklahoma County Jail to conduct high school completion classes from within its walls.

He said 100 percent of the youths in his classroom have committed felonies. That’s why they are not in juvenile detention.

“I consider this to be the end of the educational river,” he recently told Oklahoma Gazette. “This is the sum total of where we don’t want the kids to end up.”

Mihalcik cited parental struggles as the source of disruption for many of his students. When his students started falling behind in school, especially in reading, their alienation from positive influences grew.

“They get placed on the outside of certain peer groups, and they become more attractive to negative peer groups,” he said of the spiral that too often begins in elementary school.

In a phone interview, Oklahoma County Sheriff John Whetsel said he sees a school-to-prison pipeline.

He visits Mihalcik’s classroom and the juvenile pod often, where he hears young inmates’ stories. He said a common narrative starts with trouble at school and transforms to alienation, suspension and, eventually, jail time.

Whetsel sees the results of exclusionary discipline that propels youths out into a world that is very different from school.

“They find people who will love them on the street,” Whetsel said. “And they get involved in criminal activity, drugs and gangs. The next thing you know, they’re 15, 16 years old and they are here in the county jail facing … something that’s going to change their life forever.”

Neu, now in his second school year at OKCPS, said the district is working hard to reverse past practices that led to its notorious UCLA ranking.

The school-to-prison pipeline is real and readily acknowledged by many who are the closest to the process. Action is now being borne out of that acknowledgement.

Student care

Leaders of alternative schools respond to student needs in more innovative ways than in the past and in ways that schools couldn’t imagine even 20 years ago.

A full clinic, where some paid and volunteer medical and dental staff provide services for students and their children, is incorporated into the new building for Metro Career Academy.

Emerson Alternative Education Center is building a similar clinic on its campus. MAPS for Kids funding helped complete a new wing of the school’s building to house a DHS-approved child care center where students know their children are safe while they complete school. SeeWorth Academy recently installed a washer, dryer and shower for students. The school discovered that meeting basic needs like those are key to students’ success.

The methodology of teaching in the alternative programs Oklahoma Gazette explored in its alternative paths series shifted to teachers and staff being sensitive to the basic human needs of students first, before making academic demands.

Ruben now

Today, Avila is on SeeWorth’s football team and loves how he can be physical, even aggressive, in productive ways.

“I broke six chin straps this year,” he said, then smiled.

He said he plans to attend Oklahoma City Community College after graduation, using achievement scholarships and his mother’s tribal scholarship fund.

He is but one example of how low a student can get and how far a student can rise when he is provided a quality education in a school system that incorporates his human needs.

Print Headline: Inclusionary education, Alternative paths: Oklahoma Gazette’s series on alternative education ends with a closer look at exclusionary discipline and its impact on the school-to-prison pipeline.