After the abolition of slavery, black Oklahomans continued struggling in the fight for equality. They faced Jim Crow laws, which suppressed their voting rights and segregated the state, until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 gradually began to dismantle those laws.

Though Jim Crow laws were overruled, years of court challenges continued to tackle institutional discrimination. Many of those discriminatory laws continue to have lasting effects on black communities.

Institutional discrimination

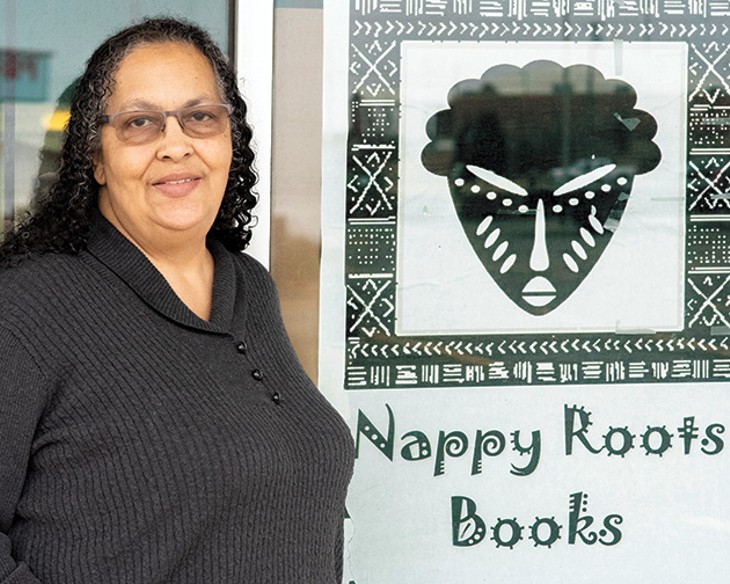

Camille Landry, a local activist and owner of Nappy Roots Books, said almost none of the advancements made during the Civil Rights era are still in effect.“Voter suppression is almost as rampant now as it was during the days where you could get lynched for registering black folks to vote, so it’s still an ongoing battle and one that we absolutely have to address,” she said.

Landry writes a guest blog for Oklahoma Policy Institute titled Neglected Oklahoma. In each post, she focuses on one issue and interviews an Oklahoman who struggles with life’s basic necessities. Issues she focuses on, like poor educational resources, poverty and mental health issues, affect minorities disproportionately. She said the biggest problem, though, is high incarceration rates, particularly in northeast Oklahoma City.

Oklahoma has the highest overall black incarceration rate, with one in 15 black males 18 years and older in prison, according to a 2016 study by The Sentencing Project. According to Prison Policy Initiative, black Oklahomans are also five times more likely to be arrested than white Oklahomans.

“Zip code 73111 has just about the highest incarceration rate in the state of Oklahoma; that’s where [Nappy Roots Books is]. The state of Oklahoma has the highest incarceration rate in the nation, and the United States has the highest incarceration rate of its own citizens in the entire so-called free world,” Landry said. “So that means that [we’re] really sitting now at Ground Zero of the incarceration nightmare.”

Landry said when people get released, they have often lost much of their support group and important assets like a car or housing.

“Once arrested, people of color are also likely to be charged more harshly than whites; once charged, they are more likely to be convicted; and once convicted, they are more likely to face stiff sentences — all after accounting for relevant legal differences such as crime severity and criminal history,” The Sentencing Project study reports.

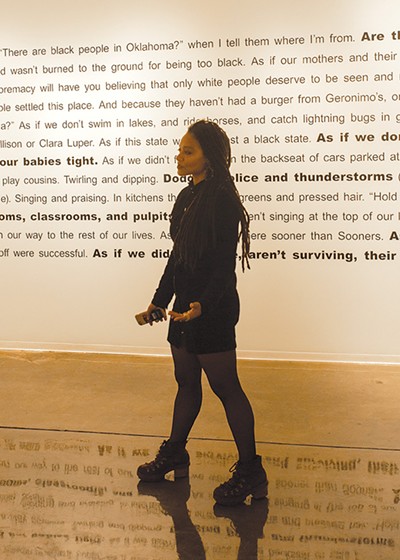

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, an Oklahoma artist, has an exhibition titled Oklahoma Is Black at Oklahoma Contemporary Arts Center, 3000 General Pershing Blvd., through May 19. She said discrimination of black people starts at an early age. One of her friends is a teacher who said her son gets punished in school for minor things.

“She tells me how her son’s teacher — her son is 7 years old, very sweet, the sweetest boy you’ll ever meet — will punish him for things that are very slight things,” she said. “We know that black and brown kids are punished more in school, are sent home more simply because they’re black and brown.”

She also has a friend who has been fired from various jobs for being black and gay, and another friend has had trouble finding a home because she is from east Oklahoma City.

“Black people deal with it in any type of way that you can, from small things to large things, from microaggressions to actually being fired from your job or having problems finding a job or getting housing,” Fazlalizadeh said. “So you’re constantly having to fight, not just stereotypes, but you’re constantly having to fight it in your everyday life — trying not to be looked at as a criminal, not be looked at as ‘bad,’ not to be looked at as ‘dumb.’ … You’re just trying to be a regular human being and live your life.”

Easing pain

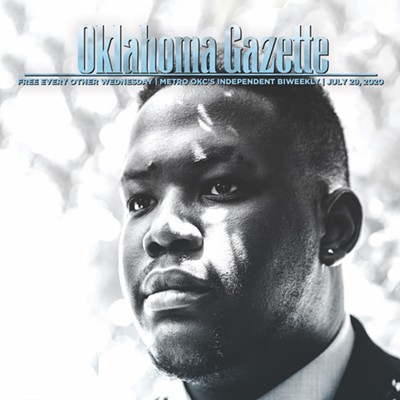

Christopher G. Acoff, a local hip-hop artist that goes by Original Flow, said he grew up surrounded by crime and prostitution in northeast Oklahoma City. It was one of the things that helped shape his love of poetry and rap and helped him realize they could be powerful tools in combating discrimination.“I gained a lot of my inspiration from that location because it was so much going on. It was prostitution, it was drugs, it was fighting, it was robberies, it was shootouts. It was like a Grand Theft Auto video game; it was something else,” he said. “The east side has definitely changed, but at the time, it was atrocious.”

He remembers when he was first immersing himself in poetry he did not have much direction about what to write. Though he witnessed crime often, one particular day made him reevaluate his writing.

“I started writing about things that I was concerned about like the world and my neighborhood and my life,” he said. “I started writing about this stuff, and it kind of grew on me. … I wanted to shine a light on what was happening in the world, and I wanted to shine a light on my life and how I was receiving those things.”

After making music that reflected some of the crime he grew up with and issues within marginalized communities, Acoff said he would hear from people who went through similar things. One of his friends told him his music inspired him to leave a gang.

Realizing the impact of his work, Acoff started writing about other important issues like depression, mental anxiety and expressing his feelings as a black man without the fear of being seen as weak.

“The root issue, I don’t think it necessarily comes from outside; I think it starts from within,” he said. “Though it is colored by a lot of outside influences. I came from a terrible neighborhood, but I don’t do terrible things and then blame it on society. I was around prostitution, I was around a lot of gang activity, I was around all kinds of stuff, but I’m not a pimp, I’m not in a gang.”

There is not an easy, clear way toward substantive progress, but Landry said action and unity are crucial. She said people in favor of equity and justice must stand up, demand change and create change in their communities and the government.

“If you do nothing, you can expect to step backwards, and at the very least, with racism being such a soul-crushing thing, at least if you stand up and fight back, it is balm for your soul. Unity is one of the most important things. … We can’t afford to fracture,” she said. “I do have to say, however, that racism is not a concern just of black people or brown people. We are the victims, we are on the receiving end, but we didn’t make the system and we, by ourselves, cannot fix the system.”