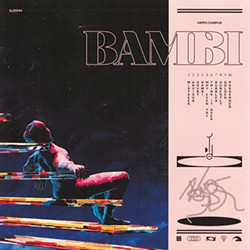

Hippo Campus guitarist Nathan Stocker said the band’s new album, Bambi, is fire. Actually, make that a fire.

“Landmark is kind of, like, dusk-ish, you know, sunset kind of, like, about to be chill,” Stocker said of the band’s 2017 debut, “and Bambi is when the sun is all the way down and you’re having a fire with your friends but you don’t know how to talk to each other because of toxic masculinity. … It’s like we found this fire that we were all standing around and we were like, ‘OK, how can we all become better people after getting warm together?’”

The band, which also includes frontman Jake Luppen, drummer Whistler Allen, bassist Zach Sutton and trumpet player DeCarlo Jackson, collectively wanted to talk about the effect toxic masculinity has in their own lives, Stocker said, because of the obvious effect it’s having on America.

“We always want to be as honest as possible with the way that we portray ourselves in our music, and obviously in our country’s climate right now, socially speaking, men are the problem,” Stocker said, “and we’re trying to figure out how to not be.”

Unfortunately, taking an honest look at the ways they contribute to the problem became complicated by their inability to fully communicate with each other during the songwriting process, which Stocker compared to a therapy session.

“There was an element of weird, like, ‘Oh, I have something to say but we don’t know how to say it directly, so we’ll just write a song about it,’” Stocker said. “And some of the songs were kind of about each other, but a lot of them are also about other people in our lives. Relationship maintenance quickly became the theme, and mental health and whatnot. … It was also kind of like, ‘Aw, damn! How passive-aggressive could we be with the songs that we were writing?’ It’s only healthy if you get what you need to say out but also deal with it in real life too; don’t just let that shit fester. … Again, the patriarchy, man, it’s a son of a bitch.”

High school, musical

The fact that the majority of the St. Paul, Minnesota, band formed in high school made some of the conflicts within the band feel more personal.

“It’s weird because you spend so much time with somebody and it’s like, ‘They know everything about me,’” Stocker said, “but then it breaks down and you’re like, ‘Wow! there’s still so much work to do when it comes to this relationship.’ So it’s, like, a daily thing. I don’t think anybody will ever have it figured out entirely, but that’s what makes the human experience worth it, I guess. You keep trying. … It’s like a marriage. You’ve gotta work on that shit every day.”

The bandmates, unable to fully communicate with each other and wanting to explore different songwriting methods from their previous releases, decided to split up to each work on their own contributions before bringing them to the group.

“We kind of just wanted to not start songs with a guitar riff and jam in a band,” Stocker said. “Well, that’s not entirely true; some of us wanted to do that, but we got into writing individually just to see how far we could take our individual visions for a song, and then we would bring them to the table and see which ones could vibe together.”

Despite the disjointed writing process, the finished product sounds like a cohesive musical statement, and Stocker credits producer B.J. Burton (Bon Iver, Low) for linking the chains.

“It’s kind of weird how that happens,” Stocker said. “You start with one song and then you’ve got another song and then, ‘Whoa! Wow! Look at this weird road we’re going down!’ And then there’s an album and it’s like, ‘How the fuck did we get here?’ … It was a real eye-opening experience listening to the album in one sitting, front to back. It’s like, ‘Whoa! What kind of journey is this?’”

Even after hearing the album, Stocker said he’s not entirely sure his contributions on “Why Even Try” and the song formerly know as “Burn the Room,” which he said was renamed “Bubbles” for “some fucking reason,” took the form he’d wanted them to.

“I’m just trying to figure that out. It’s still so confusing to me, having different versions of songs in my brain, pre-existing replicas of them,” Stocker said. “It’s kind of hard to know which one is more valuable, I guess, which is kind of stupid. I mean, they’re all good. They all, at the end of the day, serve their own purpose, but I am happy with how everything turned out. It’s a crazy-weird record, but it’s all right. It’s cool.”

Blaming Beatles

Songs, like people, transform over time, and it’s not always evident that the alterations are improvements.

“You’re like, ‘Oh, man! I don’t know why something changed when I just wanted it to be the same way as it was,’” Stocker said. “You feel that with old songs too. The songs that people love and the songs that you know and love, you’re different now and the way that you play them is different, and it’s like, ‘Wow! How do we adapt that live?’ It’s really kind of stressful sometimes. … But why try? Make it something new. Let it exist in a different way.”

While he’s not sure the album offers any solutions, recording Bambi helped the young men in Hippo Campus more clearly identify the problems they struggle with.

“I don’t know about answers, but the most important part was definitely just asking the questions in the first place,” Stocker said. “I don’t know if the answers exist, but the important thing is that the questions do.”

The album’s effect on the band’s fans is also difficult to judge, Stocker said, because the discussion surrounding it seems one-sided.

“Our fan base is mostly female, and talking about masculinity and the way that it should be is definitely a topic, but when it comes to actually employing different methods of changing the way that we approach it, it’s kind of hard to do just because we don’t have a large male audience,” Stocker said. “We don’t get to talk to as many male fans as female fans, and I think both parties are definitely significant in that conversation.”

When asked why Hippo Campus’ fan base is so predominately female, Stocker briefly discusses the way the band was marketed in its early days on social media before pointing the finger back several decades to one of rock’s first heartthrob phenomena.

“I think the Beatles are to blame,” he said.

Visit thejonesassembly.com.