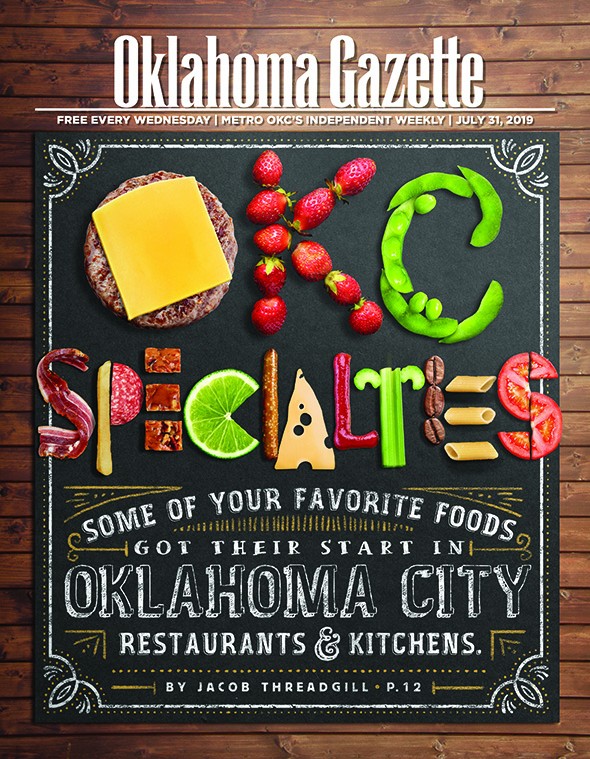

Over the past decade, regional food preparations started to become mainstream. Poke, once a Hawaiian specialty, is now one of the fastest-growing restaurant concepts in the country. It joins city-signature dishes like Nashville hot chicken and Minneapolis’ Juicy Lucy cheese-stuffed hamburger among the former regional favorites that can now be found nationwide.

Which unique Oklahoma City regionalized food innovations could be next? There are a few Oklahoma traditions that we might take for granted, like the Club Special drink and Aunt Bill’s Brown Candy, that could blow up. Of course, Oklahoma has plenty to contribute in the hamburger realm, but it goes beyond the onion burger and even in the crowded pizza market. Oklahoma City offers innovations that cannot be found elsewhere.

Fried pepperoni pizza

Detroit-style pizza, which is twice baked in a well-oiled, deep rectangular pan to become extra crispy, has started to go national. The style that was once a Motor City staple can now be found alongside Neapolitan-style pizzerias in New York and makes its Oklahoma City debut with the opening of Providence Pizza at Parlor in late August or early September.Oklahoma City’s own pizza innovation is the fried pepperoni, and its exact origins date to the city’s first restaurant serving pizza. Jake Samara and Jack Sussman brought Oklahoma City its first pizza place, Sussy’s Italian Restaurant, inside Nomad Club in 1947. The item followed Samara and went to Sussman through a variety of concepts over the years, according to Mike Sills, Samara’s nephew. Rick Bailey — who purchased Nomad II from Sussman in 1980 — takes credit for updating the pizza concept after taking inspiration from a meal at The Palm in Dallas in the mid ’80s.

“They fried these onion rings super-thin [at The Palm], and we came back to the Nomad and started playing around with different fried items and threw some pepperoni in there, put it on a pizza and it was on the menu a week later,” Bailey said.

Nomad II closed in 2016, and Bailey opened a Sussy’s concept with the fried pepperoni pizza in Bricktown in 2017, but it closed in 2018. Bailey is looking to bring another Sussy’s location to northwest Oklahoma City in the future.

The fried pepperoni concept has lived beyond Sussy’s. Wheelhouse Pizza Kitchen, a short-lived concept on N. May Avenue, featured the fried pepperoni as a nod to Nomad II, but it lacked the distinct crispness of his predecessor.

“There is a trick to get them how you want, the pepperoni,” Bailey said. “When done right, it gets almost a bacon flavor.”

Ned’s Starlite Lounge, which operates in Nomad II’s former location at 7301 N. May Ave., includes a Nomad burger on its menu with fried pepperoni, sautéed peppers and onions, mozzarella and a roasted garlic tomato reduction.

Sparrow Modern Italian, 507 S. Boulevard Ave., in Edmond has taken the fried pepperoni concept to an exponential level. Pizza is baked with cheese, sauce and a layer of pepperoni. It is then topped with a tower of fried pepperoni.

Sparrow owner Pete Holloway said he was aware of Bailey’s version of fried pepperoni, but Sparrow has a different presentation.

“Chefs Joel [Wingate] and Jeff [Holloway] were playing around about maybe putting the fried pepperoni as an appetizer and came up with idea to stack it high on the pizza,” Holloway said.

The fried pepperoni seems to be another iteration of a new pepperoni craze that comes from Ohio and is taking New York pizzerias by storm: the cupped pepperoni in which small discs of pepperoni bubble on the pie in the oven, forming crispy edges with a pool of grease in the center. Locally, The Jones Assembly and Hideaway Pizza locations offer a version of the cupped pepperoni.

On the vast expanse of the internet, there are no returns for a restaurant outside Oklahoma serving a deep fried pepperoni pizza.

“As far as I believe, my father and I are the first that have ever done fried pepperoni on a pizza anywhere,” Bailey said. “We think we are the inventors. I can’t prove it, but I can’t find any place that did it before us.”

Theta burgers

Rumors of a national burger chain entering the Oklahoma City metro market seemingly pop up every year. The most recent example came from Moore city councilman Mark Hamm, who issued a false statement that Wahlburgers — the chain founded by actor brothers Mark and Donnie Wahlberg — would be coming to his district.After a corporate spokesperson corrected Hamm that there are no plans to enter the market, it gave flashbacks to the elaborate 2018 April Fool’s Day prank that placed an “In-N-Out Burger coming soon” sign along Northwest Expressway.

It begs the question, Why does Oklahoma City need these chains when it already has one of the most unique and robust regional burger histories in the country?

According to national hamburger scholar George Motz in his book The Great American Burger Boom, it was long-forgotten Hamburger Inn in Ardmore that invented the fried onion burger — the sandwich most synonymous with the Sooner state — as a Depression-era necessity. These days, El Reno is the country’s onion burger capital, where Sid’s Diner, Johnnies Hamburgers & Coneys and Robert’s Grill carry on the tradition.

In Oklahoma City, Nic’s Grill, Tucker’s Onion Burgers and S&B’s Burger Joint, among others, have taken the onion burger beyond the metro thanks to expansion — or in the case of Nic’s, an appearance on Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives.

It is University of Oklahoma sorority chapter Kappa Alpha Theta that led to the popularity of another regional favorite. According to The Oklahoman’s Dave Cathey, when Ralph Geist opened Town Tavern in what is now Campus Corner in 1937, a burger topped with hickory sauce, mayonnaise, pickles and cheese became so popular among the sorority and fraternity crowd that Geist began writing the name Theta Special on order tickets.

The Theta burger made its way on the menu at the Split-T under owner Vince Stephens, who opened The Joint in Oklahoma City on Western Avenue in 1953. Stephens hired Johnnie Haynes to manage the Split-T until Haynes went out on his own to found Johnnie’s Charcoal Broiler, where the Theta is the No. 9 on the menu.

Johnnie’s Charcoal Broiler has taken the hickory sauce, which Cathey wrote was originally known as Comeback Sauce and served at Ralph and Amanda Stephens’ Dolores Restaurant as early as 1925, and made it its own. The tomato-heavy sauce is sold by the bottle at Johnnie’s, and its secret is closely guarded by the Haynes family, who will not even allow high-level employees to know what goes into the recipe.

The same goes for another signature, the Caesar burger.

The Theta burger has drifted into Texas and across Oklahoma, but many imitators opt for a sweeter barbecue sauce over the more savory hickory like the original.

“There are a lot of wannabes, and I don’t mean that the wrong way, that don’t make their own dressing,” said Johnnie’s Charcoal Broiler co-owner Rick Haynes. “There are a lot of Theta burgers out there that don’t use hickory sauce. They use barbecue, which is fine. Someone copying you is the best compliment.”

Club Special

A refreshing adult concoction of vodka, limeade, Sprite, club soda and lemon and lime wedges is the best way to beat the heat during the Oklahoma summer, whether you are on the golf course, by the pool or finding a reprieve in the air conditioning.Oklahomans instinctively know the drink as a Club Special — but you’ll get blank stares from bartenders if you try to order it anywhere else in the country.

The drink’s origins belong to Twin Hills Golf & Country Club, but an exact date might be lost to time. Longtime bar manager Clarence Casteel and bartender Charlie Clemmons helped popularize the drink in the 1960s, said Twin Hills general manager Paul Hughes.

“We’ve been open since 1921, and I’d think we’ve been serving it almost that long,” Hughes said. “I started working a Oak Tree [Country Club in Edmond] in 1979, and they served the Club Special there back then. Everyone has their own version and puts a twist on it, but Twin Hills’ is the best. The drink remains very popular. It goes down smooth, or so I’m told — I don’t drink, but everyone says they’re good.”

Twin Hills always serves the drink over ice, but the bar Good Times, 1234 N. Western Ave., offers a frozen version made with vodka, sprite and sweet and sour.

“My whole life, I thought [the Club Special] was a regular cocktail, but if you went to another state to order it, they would have no idea what you’re talking about,” said Good Times co-owner Claire Hampton.

Aunt Bill’s Brown Candy

A holiday tradition in Oklahoma is the finicky brown fudge Aunt Bill’s Brown Candy that dates to a 1928 column by The Oklahoman’s food columnist Edna Vance Adams, who wrote under the nom de plume Aunt Susan. According to Cathey, the newspaper published the recipe every year for the next 15 years, and it started to become Oklahoma heritage.The nut-filled sugary confection has the temperament of an Oklahoma springtime weather pattern. Perhaps it comes as no surprise that it takes the same fortitude to withstand surprised thunderstorms sweeping down the plains without the warning of modern weather radar that is required to wrestle Aunt Bill’s Brown Candy into a perfectly smooth mixture.

Woody Candy Company, which was founded by Lucille and Claude Woody in 1927, remains the only commercial operation committed to producing the candy on a commercial level.

“It’s legendarily difficult to make because the labor is tough and you need to get the atmospheric conditions and chemistry right,” said Woody Candy co-owner Brian Jackson.

Woody Candy Co. sells Aunt Bill’s Brown Candy from its storefront at 922 NW 70th St. as a commitment to Oklahoma history, even though it is not the best from a business overhead perspective. Jackson said they have to donate portions to local food banks because batches do not always meet the company’s standards.

“If you mess up one of those three or four variables in the slightest bit, it’s going to ruin the batch,” Jackson said. “It takes four to five man hours of labor plus ingredient cost before you have the first indicator of whether or not the consistency came out right, but there are many checkpoints [for something to go wrong]. You won’t know until the next morning if it came out correctly.”