I’m writing on the day we celebrate the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Many people observe the holiday by doing a service project, and I just returned from helping OCU students make a thousand sandwiches for the Homeless Alliance. We mostly remember the “I Have a Dream “ speech King and forget the last five years between the March on Washington and his assassination on the balcony of the Lorraine Hotel in 1968. That’s when he grew increasingly convinced that, as he told his friend Harry Belafonte, we might be integrating people into a house that was burning down. Without economic justice there is no social justice.

In a book that should be required reading in every school—that is, if we weren’t trying to keep our students from learning the truth—King wrote about the need for systemic change, not just an end to the most overt and vile forms of segregation. The book was called, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? It made King into the enemy of more than just white supremacists. It turned “white moderates” against him when his sermons shifted from racial equality to those reforms necessary to address the forces that kept Black people from achieving self-sufficiency and social mobility.

Exactly one year before King was murdered, he spoke at the famed Riverside Church in New York City. On the upper west side of Manhattan, just blocks from Wall Street, King spoke directly to the vast inequality of wealth in America (which is far worse today), reminding a mostly white and wealthy audience that the black soldiers fighting in Vietnam were there to protect freedoms that many would not enjoy when they returned home. The next morning, in the liberal New York Times, the paper’s own editorial was entitled, “Dr. King’s Mistake.”

In it, the editorial board criticized King for venturing outside of his area of moral expertise (integration) and into the world of economics, which he should leave to the “experts” of predatory capitalism. What they really meant of course, is that it’s one thing for a prophet to speak to the condition of the human heart, but the red line for corporate America is the sanctity of a system that produces and protects wealth for the already wealthy. King had this strange idea that we should help the people who need help, not the ones who don’t.

It is one thing to protest the shameful segregation of Jim Crow, but do not talk about reparations or higher wages, or someone is liable to pay a redneck to shoot you. Sentiment is one thing we are all entitled to, but do not cross the golden calf. We will name streets after Dr. King, and observe his birthday, and condemn systemic racism, but leave banking regulations to banks, and redlining to mortgage companies. As for unions, my evangelical friends tell me that Jesus is against collective bargaining.

People forget that the March on Washington was for jobs and freedom, not just for making speeches and singing “We Shall Overcome.” In his later years, King would explain that there are really two phases of the civil-rights movement. The first was to recognize the humanity of Black people. The second was to work toward true community and equality. This requires more than a change of heart, although this is a first step. After changes in the law that made the most obvious segregation illegal, the second phase has been more than just illusive. We have actually gone backwards, especially with the frontal assault on voting rights.

The truth is that it is painful to acknowledge that so much of what King preached against is still with us. In The Guardian, British journalist Gary Younge wrote: “The codified obstacles to freedom and equality have been removed, but the legacy of those obstacles and the system that produced them remains. Black Americans are far more likely than white people to be stopped, frisked, arrested, jailed, shot, and executed by the state, while the racial gaps in unemployment are the same as 40 years ago, the racial disparity in wealth and income is worse than 50 years ago … [People of color] have the right to eat in any restaurant they wish; the trouble is, many can’t afford what’s on the menu.”

So let us keep marching but let us do more than march. Let us look long and hard into the enduring soul of racism itself. It is in all of us. As for the inconvenient truth of prophets, let us remember that we have always stoned the real ones to death. Several years ago, the cover of The New Yorker showed Martin Luther King Jr. kneeling on the sidelines of an NFL game with Colin Kaepernick. It reminded us of what King would be doing today and why so many of us would still hate him.

To conclude on a personal note, I had just become captivated by the voice of Dr. King as a teenager, when at the age of 15, on a fishing trip with my preacher father, the news came of his assassination. It was one of the only times I saw my father cry. Just two months later, the best of all the Kennedy brothers, in my opinion, and probably the next president, Bobby was also shot dead. A darkness fell across that spring in 1968 that is hard to imagine if you did not live through it.

So, what shall we do? To begin, let’s try to appreciate why King has been both sentimentalized, misunderstood, and misrepresented. And then us work to make the dream a reality, even when it requires sacrifice. Here is one of King’s lesser-known quotes: “If you can’t fly then run, if you can’t run then walk, if you can’t walk then crawl, but whatever you do you have to keep moving forward.”

So, we shall. And one day,

Overcome.

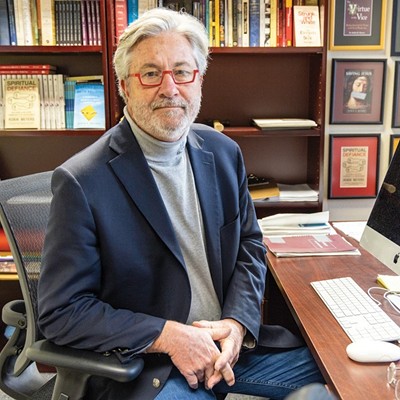

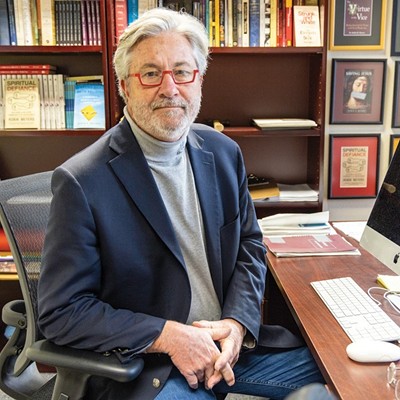

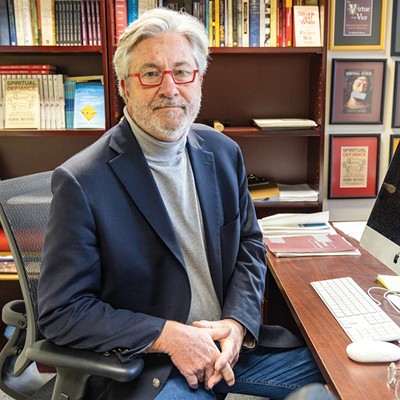

The Rev. Dr. Robin Meyers is pastor of First Congregational Church UCC in Norman and retired senior minister of Mayflower Congregational UCC in Oklahoma City. He is currently Professor of Public Speaking, and Distinguished Professor of Social Justice Emeritus in the Philosophy Department at Oklahoma City University, and the author of eight books on religion and American culture, the most recent of which is, Saving God from Religion: A Minister’s Search for Faith in a Skeptical Age. Visit robinmeyers.com.