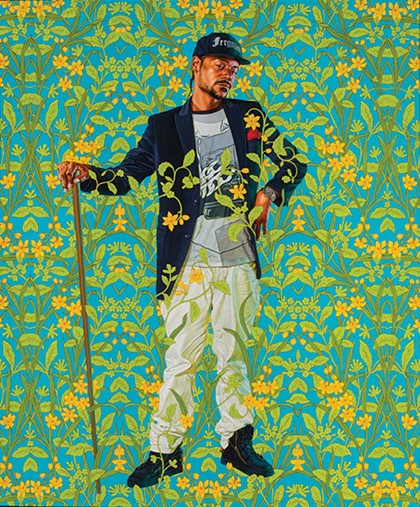

Known for painting Barack Obama’s official presidential portrait, artist Kehinde Wiley’s neoclassical work typically features people of color — subjects not fully represented in art museums.

“What I do in my own work is to look at the canon but to imagine people who look and feel like I do,” Wiley said in the 2014 PBS documentary Kehinde Wiley: An Economy of Grace.

He elaborated on this idea in an interview with St. Louis’ Higher Education Channel.

“It’s important when thinking about art and thinking about museums to think about how one mirrors or sees themself in the work that’s on the walls,” he said. “There’s a type of permission being given when you are a young artist, and you walk into a museum and you happen to see someone who looks like you.”

Oklahoma City Museum of Art (OKCMOA), 415 Couch Drive, recently acquired Wiley’s 2018 portrait “Jacob de Graeff,” and director of curatorial affairs Michael Anderson said the museum has organized an entire gallery around it on the second floor, which was recently vacated following the departure of the exhibition Victorian Radicals: From the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts and Crafts Movement.

“It was very fortuitous timing,” Anderson said, “because then we were able to build one of the galleries around that work, and it became kind of a key piece in our new exhibition on the second floor. … Each of the galleries on the second floor has a different theme or genre. We had one gallery that we wanted to focus on portraiture, and when we acquired that Kehinde Wiley, we knew that would be a work that would be kind of a focal point for the space, and with that then we wanted to have other works that related in some way to it that were at least close by within that gallery. … We knew that this would be a popular work in the installation, and we knew that it would be a central work when were reorganizing our portrait gallery.”

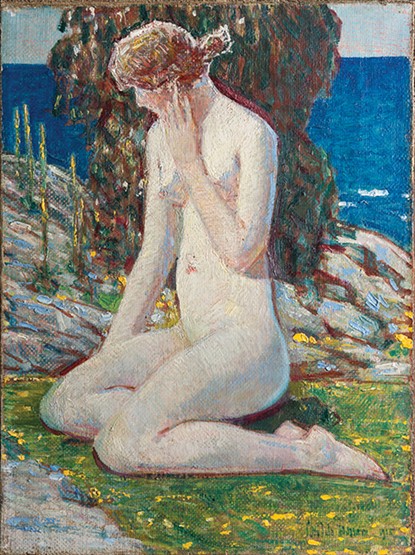

From the Golden Age to the Moving Image: The Changing Face of the Permanent Collection — which also features still lifes, landscapes, nude studies, video art and more by artists including Pierre-Auguste Renoir, George Bellows, John Singleton Copley and Georgia O’Keeffe — is on view through 2020.

OKCMOA hosted the exhibition Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic in 2017, and Anderson said the museum has been “keen to acquire” one of Wiley’s portraits for its permanent collection ever since. “Jacob de Graeff,” painted in oil, features Brincel Kape’li Wiggins Jr., a man Wiley met on the street in Ferguson, Missouri, in a pose reminiscent of Dutch painter Gerard ter Borch’s 1674 portrait of Amsterdam regent Jacob de Graeff. Wiley’s portrait was originally included in the Saint Louis Art Museum exhibition Kehinde Wiley: Saint Louis.

“Kehinde really connected with our community. We didn’t want it to just be a one-time thing.” — Michael Anderson

tweet this

“This is a piece that we all agreed was the most dynamic and interesting,” Anderson said. “It’s a large-scale work, which we find very exciting to begin with. There’s a very strong male subject in the work, and it’s a work that has kind of a political undercurrent with the Ferguson ball cap that the sitter is wearing. So all these things just sort of pointed to the fact that this is a significant new work. We didn’t want to just necessarily acquire any Kehinde Wiley. We wanted to acquire the right Kehinde Wiley and a work we think is really important for his career.”

The name “Ferguson” became politically charged in 2014 when police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown, an unarmed black 18-year-old man, in the St. Louis, Missouri, suburb, setting off weeks of protests met with a militarized police response.

Though Wiley was born in California and is based in New York City, Anderson said “Jacob de Graeff” makes more sense displayed next to a 17th century work by Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck than it would among the museum’s collection of early American paintings, which includes a portrait of George Washington.

“Kehinde Wiley, he’s going back to European sources in many cases, so he’s basing it on 17th century Dutch sources,” he said. “In the colonial American art that we have there are different styles at play, but for the most part, they’re artists that were actually, in one form or another, creating a new American style that was in some way distinct from European sources. … What’s really interesting about Kehinde is he’s obviously creating a new art, but it’s an art that really does look back to old masterworks, especially European sources. … What he’s doing is sort of recreating what you see in a museum, and American art has an interesting relationship to that because, historically … for a lot of museums, great old master art meant European art. American artist is kind of a new entry into a lot of collections around the world, and Kehinde is changing who we see in galleries and he’s doing it on this historical sort of Eurocentric model.”

Code switching

“Artists are people who occupy different spaces, and I think a lot of — not only artists but people of color — know what it means to code-switch,” Wiley told Time. “Being able to occupy multiple spaces, in a way, exemplifies where America is. The conflicting twin narratives that can be at once appalling and beguiling exist in all of us, and I think that’s part of what my work is about.”

The Changing Face of the Permanent Collection features video art from recent decades, but most of the portraits are from 1920 or earlier. The fact that Wiley’s painting is from just last year and features a contemporary black man in a pose once held by a European aristocrat gives it a special significance to viewers, Anderson said, and this modern relevance made the museum’s 2017 exhibition of Wiley’s work popular with visitors, many who returned more than once.

“Kehinde really connected with our community,” Anderson said. “We didn’t want it to just be a one-time thing, but we wanted it to be part of our identity moving forward as an institution. … Relatability in art in general is certainly an important aspect to it. Not to put too fine a point on it but … I think it does draw a broader, more diverse audience. His exhibition certainly did, and I suspect this painting will, as well.”

Admission to OKCMOA is free-$12. Visit okcmoa.com.