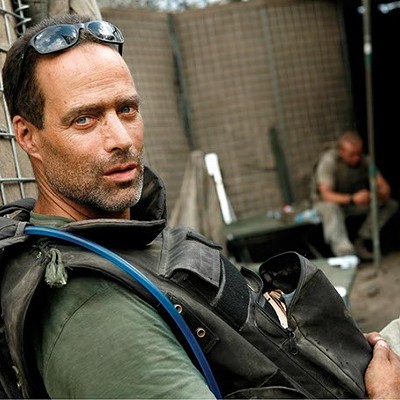

Few works — literary or cinematic — effectively merge romanticized war (a machismo-ridden and valorous endeavor to preserve the free world and hopefully return to a darling back home) with the assumed misanthropy of a grotesque battlefield. David Ayer’s Fury presents such a hybrid; despite a general lack of exposition (save a brief title card), the film provides a momentary glimpse into a violent institution while maintaining Hollywood luster beneath gallons of gore and expletives.

Focusing on the crew of the eponymous tank, Fury dissects a group of would-be clichés. Wardaddy (Brad Pitt, World War Z) is first seen pouncing on a lone S.S. horseman from the bowels of a machine graveyard, establishing his demeanor as a scrappy guerilla fighter with a reckless paternal instinct for his crew. Shortly thereafter, Bible (Shia LaBeouf, Nymphomaniac), Gordo (Michael Peña, American Hustle), Coon-Ass (Jon Bernthal, The Wolf of Wall Street) and the remnants of a recently deceased gunner are introduced within the belly of the vessel. Returning to base, the men induct Norman (Logan Lerman, The Perks of Being a Wallflower), a displaced typist assigned to copilot Fury. In perhaps an allusion to Randall Jarrell’s “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” Norman’s first trial requires him to “wash out” his unfortunate predecessor, taking a few too many moments to ponder a piece of face with an eerily human presence.

The narrative that follows, on an overt level, is rather linear: The crew propels the allied front forward, facing both unrealistic odds and copious emotional turmoil.

To a grand effect, however, Ayer opts to focus on two distinguishing variables. First, the film diminishes the notion of the men as paragons of righteousness, as both the nation they represent and their inability to retain their composure with the enemy at their mercy is never veiled with a moral backdrop. Rather, the men’s home is the war machine’s womb, and their sporadic animalism is conveyed as such, nothing more.

Though Pitt inherently assumes the leading reigns readily, Lerman emerges as an accurate parallel to Wardaddy. Arriving as a greenhorn with minimal training, Norman is ferried by Wardaddy into an orgy of violence and drunken revelry. In a particularly disturbing instance, the sergeant physically forces Norman to execute a surrendering S.S. operative who begs hysterically for his child. After the hazing, Norman exhibits a gradual and robotic pleasure for slaying Germans, as well as an encouraged entitlement over prisoners of war, eventually spawning an appropriate war name: Machine. In contrast and shortly before the arrival of Norman, Wardaddy crouches down unseen to emit a wince of sorrow, not only for his fallen squadmate but seemingly for the violent constant that is his life. In doing so, Pitt plays the most disturbed and terrifying role of his career as he expertly bounds between tendencies of Eros and Thanatos.

The rest of the cast do well to maintain the film’s trajectory but are dimly lit in comparison to the display Pitt and Lerman put forth. Though the film appears to opt for a general accessibility by means of Nazi-killing, artillery and belching, Fury subtly slides a few rounds of critical concoctions, thus delivering a film far more contemplative than Ayer is known for.