For the past three decades, the City of Oklahoma City has invested more than $1 billion in downtown to improve residents’ quality of life. With an emerging downtown, residential populations have grown alongside high-profile projects, like the 1-cent sales tax MAPS capital improvement initiatives and commercial projects backed by city subsidizes.

From newly constructed trendy apartment buildings in commercial districts like Midtown, Deep Deuce and Automobile Alley to rehabbing homes in long-standing urban neighborhoods like Mesta Park, the Paseo, Jefferson Park and Classen’s North Highland Parked, Oklahoma City is well on its way toward a more vibrant and livable urban core. These days, newly attracted residents, along with existing residents, are enjoying more walkable neighborhoods, new restaurants and bars, entertainment venues and shops. But missing from urban improvements is a grocery store where residents can get day-to-day basics.

Oklahoma City is far from alone, as many revitalized American cities are slow to attract that critical mass of retail, leaving residents to either travel into the suburban areas to shop at full-service grocery stores or rely on convenience stores, local ethnic grocery stores or high-priced gourmet food shops for their fresh food needs. While a majority of Oklahoma City’s urban core is not considered a federally designated food desert, it can feel that way when there are few options for fresh, high-quality, healthy and affordable food.

Oklahoma City’s urban grocery store gap is beginning to feel some movement.

Momentary makeover

For more than four decades, urban residents have turned to the 22,000 square-foot grocery store at the corner of NW 18th Street and Classen Boulevard for their shopping needs. Located near the entrance to Mesta Park and across from neighborhoods like Classen Ten Penn and Gatewood, the one-story grocery store opened as a Safeway in 1973.

It opened during a time of suburbanization, as downtown and urban residents moved north and south. The grocery store, which eventually became a Homeland, continued to serve customers. As grocery stores modernized and expanded selection and services, this store remained mostly unchanged, even amid downtown improvements and rapid gentrification in nearby neighborhoods.

Last February, Homeland officials made public their plans to commit $2 million to modernize the store’s exterior and renovate the interior, making way for an organic and fresh foods section, a new bakery and deli and a full-service meat counter. Following national grocery store trends, the renovated Homeland would become home to a freshly prepared food section serving up everything from sandwiches to sushi, pizza and entrees to take home or to the office.

In mid-August, nearby residents began to hear that their store’s project was not moving forward as originally scheduled. Brian Haaraoja, senior vice president of merchandising and marketing, explained that before work began, contractors notified the company that the scope of the project had increased; new plans included a new roof and HVAC replacement system. The project, which now comes with a nearly $3 million price tag, faces an estimated completion date of summer 2018.

“The bottom line is it will take longer than we thought,” Haaraoja said after explaining the delays to Oklahoma Gazette. “We’ve gotten to the point where we are going to get started on replacing the roof, HVAC system and major plumbing work. We will do that before we can start renovations inside.”

Interior renovation will begin in February following the busy Thanksgiving and Christmas food shopping holidays.

“We really feel it is the right thing to do,” Haaraoja said. “We’ve had great community support. We are excited about it. We are disappointed it is a little more work than we originally thought. It is still well worth it. When it is all done, we will have a beautiful store.”

Felt absence

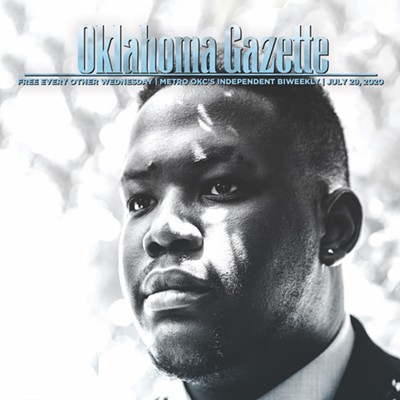

As a longtime resident of northeast Oklahoma City, Ward 7 Councilman John Pettis Jr. has passed the same empty storefronts hundreds of times. Each time, they served as reminders that the basic amenities were missing in his ward. Amenities like grocery stores and the retail that follows them have been missing for decades in northeast Oklahoma City, where several areas fit the federal definition of a food desert. As a child, the Pettis family traveled from their northeast Oklahoma City home to Midwest City for grocery shopping. His family wasn’t alone.

In 2013, when Pettis campaigned for the Oklahoma City council seat, an issue of his campaign was grocery stores. Pettis viewed grocery stores as an answer to poor health outcomes and community revitalization as well as economic development through job creation or tax revenue generation.

“A few years ago, the Oklahoma City-County Health Department talked about northeast Oklahoma City ZIP codes as some of the unhealthiest in the metro area,” Pettis told Oklahoma Gazette. “One of the reasons is the lack of access to food, quality food. There are not choices in northeast Oklahoma City, and that creates a negative impact on health and in other areas. Grocery stores attract other retail. Grocery stores attract residents.”

The food disparity is an echo of northeast Oklahoma City’s history, a mostly minority community marked by decades of economic distress. Around 22,000 of northeast Oklahoma City’s 33,000 residents reside in the urban ZIP codes of 73105, 73111 and 73117, which are currently home to two grocery stores.

After his election, in an attempt to solve the grocery store dilemma, Pettis proposed the creation of a tax increment financing, or TIF district, in Ward 7. Within a TIF district, property taxes are frozen at the existing level. Future growth, over a period of time, goes to the TIF fund for project financing. After witnessing TIF districts in Fort Worth, where city leaders distributed TIF subsidies to developers of grocery stores, Pettis pushed for the Northeast Renaissance TIF.

A year after the council approved the TIF, Pettis and community dignitaries broke ground on Northeast Town Center, a $7 million redevelopment project along NE 36th Street. As a partially TIF-funded project, Pettis promised residents they would see a grocery store locate to the shopping center. Earlier this month, Save-A-Lot, a national discount grocery, announced its plan to anchor the center.

While Save-A-Lot is not a full-service grocery store, Pettis said the store meets the goal of increasing access to fresh and healthy food choices in northeast Oklahoma City. He believes the store is a start to ongoing efforts to bring more grocery stores, including a full-service grocer, to the area. The northeast Oklahoma City store could open before the end of the year.

“Last year, I went to a grand opening of a [Save-A-Lot] store in south Dallas,” said Pettis, who explained the economic and health statistics of the area matched northeast Oklahoma City. “I was so amazed to see people standing in line around the corner trying to get into their particular store. You had a community who did not have a grocery store for decades. This was now their store.”