Great jazz musicians possess the nerve and skill to improvise beyond written notes on a page, becoming bare for criticism or praise with each newly formed measure.

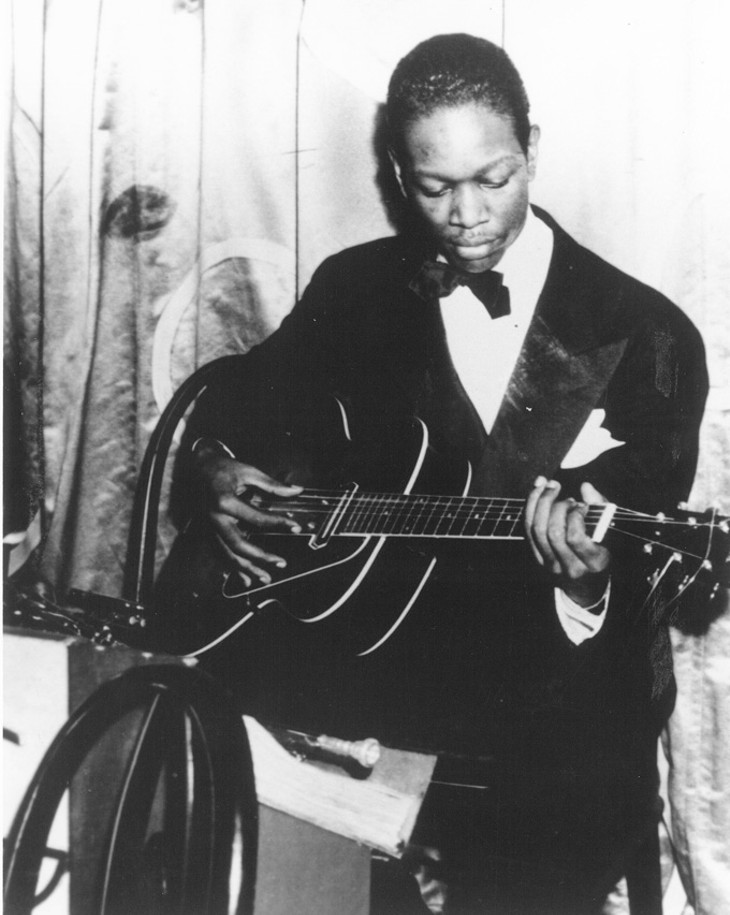

As testaments to this strength, these artists are often recognized as individuals rather than part of a band. Oklahoma City’s Charlie Christian was one such talent who stood out without accompaniment.

Christian is known as the first major solo guitarist who brought the instrument out of the rhythm section. Despite a short career before tuberculosis led to his untimely death at age 25, Christian is cited by many renowned artists — such as Wes Montgomery, Carlos Santana, B.B. King and T-Bone Walker — as a key influence in their musical development.

At the American Jazz Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, Christian is one of 11 musicians highlighted in a guitar- focused exhibit.

“The world doesn’t know how fantastic he was,” notes a quote by jazz pianist Mary Lou Williams at the museum.

One important influence in Christian’s life was Deep Deuce,

the African-American business and entertainment district in Oklahoma City where he performed during adolescence and young adulthood.

Like segregated areas across the nation at the time, Deep Deuce — centered around 300 NE Second St. — faced its share of discrimination and poverty. But these circumstances didn’t deter Christian and his counterparts (including author Ralph Ellison and jazz singer Jimmy Rushing) from achieving international notoriety.

This summer marks 75 years since Christian launched his music career from Deep Deuce, a neighborhood that inspired multiple generations of innovative artists.

Renaissance man

Best known for writing the award-winning Invisible Man, Ellison compiled essays about the era Christian and he lived in for 1964’s Shadow and Act.“With Christian, the guitar found its jazz voice,” Ellison wrote. “With his entry into the jazz circles, his musical intelligence was able to exert its influence upon his peers and to affect the course of the future development of jazz.”

Born in Bonham, Texas, in 1916, Christian moved to Oklahoma City as a toddler and considered it his home.

The jazz guitarist’s early inspirations came from his creative family. His blind father was a singer, trumpet player and guitarist, and his mother played piano. Christian’s two brothers, Clarence and Edward, also were musicians. Edward was once a member of the Blue Devils, a prominent Oklahoma City jazz group that included notable musicians like William “Count” Basie. The Blue Devils and Western swing kings Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, which Christian listened to on the radio, were especially influential in shaping Christian’s music. Jazz artists from around the country came to Oklahoma City. Among them was saxophonist Lester Young in 1929, who Ellison recalled as “perhaps the most stimulating influence upon Christian.”

“Deep Deuce is a working laboratory where [Christian] can hear the musicians coming through and play with them,” said Hugh Foley, professor of fine arts at Rogers State University and author of Oklahoma Music Guide. “Since he was a kid, he’s had constant on-the-job training.”

Growing up in a poor neighborhood near Deep Deuce, Christian, his father and two brothers played music in Oklahoma City’s white neighborhoods to make money or receive clothing and food. Christian constructed his first guitar from a cigar box.

While struggling to survive, his family found comfort and freedom in music. The all-black Frederick A. Douglass High School, from which both Christian and Ellison attended, also strongly encouraged music as a discipline, in large part thanks to educator Zelia Page Breaux, who taught Christian how to play the trumpet. Christian’s trumpet lessons likely contributed to his notable “hornlike” sound on the guitar. Breaux was a significant influence on multiple jazz musicians graduating from Douglass.

In Shadow and Act, Ellison recalled how he and at least a dozen other African-Americans, who were all living in Oklahoma City, considered themselves Renaissance men. The author wasn’t sure how they acquired this title but wondered whether Oklahoma City — still heavily segregated at the time — contributed to this label, as the city was “not so tightly structured as it would have been in the traditional South, or even in deceptively ‘free’ Harlem.”

But the most likely reason, Ellison believed, they held this esteem was from a teacher’s encouragement to strive beyond the social environment.

Anita Arnold, a 1957 Douglass graduate and executive director of Oklahoma City-based Black Liberated Arts Center Inc., said the school’s excellence continued into her era.

“Our principal had such high standards for us,” Arnold said. “Whatever our teachers said, we took it to heart.”

Another way this time period in Oklahoma contributed to the jazz movement, Ellison believed, was the frontier mindset of a state just a few decades old; an American frontiersman is in “all ignorance of the accepted limitations of the possible,” the author wrote.

Deep world

When producer John Hammond heard Christian perform in Oklahoma City (thanks to Mary Lou Williams’ recommendation), he immediately wanted him to join the Benny Goodman Sextet. Being associated with Goodman — one of the most popular big band acts of the era — helped Christian receive international recognition.After performing with Goodman’s group, Christian would join other pioneers in the bebop or modern jazz movement for all-night jam sessions, most notably at Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem.

While traveling around the country, Christian still came back to Oklahoma City when possible and performed with local friends.

Thanks to the train system, jazz traveled throughout black towns from Oklahoma City to Kansas City and beyond. Through his research, Foley found the region’s jazz era could have easily been called Oklahoma jazz or Southwestern jazz, but the name Kansas City jazz stuck because the city became a hub for a large party scene where liquor sales were prevalent.

“Kansas City’s legacy manifests itself in bebop,” Foley said, “and within that range comes other guitarists whose essential foundation is the Christian sound.”

In 1942, Christian died of tuberculosis at a New York hospital. His funeral was at Oklahoma City’s Calvary Baptist Church in the Deep Deuce neighborhood. Memorials also were held for Christian in Chicago, New York and at the cemetery in Bonham where he’s buried next to family.

Lasting legacy

From her office on Lincoln Boulevard, just a few miles north of the capitol, Anita Arnold sits among countless artifacts and walls covered in African- American-inspired art and photographs. Much of this collection revolves around Christian, including a frame made from the wood of his now-demolished boyhood home in Bonham.As the executive director of Black Liberated Arts Center (BLAC) Inc., Arnold has arguably become the most prolific expert on Christian’s history. While she’s a fellow Douglass graduate and spent time in Deep Deuce when it was still an all-black community, Arnold didn’t know much about Christian before joining the nonprofit in the mid-1980s. BLAC Inc. organizes the annual Charlie Christian International Music Festival, which celebrated its 29th year in May.

“For the first festival on Deep Deuce, the area was in ruins,” Arnold said. “There was a lot of garbage, broken bottles and overgrown grass. We had volunteers that cut down the weeds and picked up trash. We were cleaning up Second Street.”

By the early 1990s, the festival grew to 40,000 in attendance. Arnold and others from the time agreed the Christian festival motivated the city to redevelop the Deep Deuce district. But with that came what Arnold said was “distrust” from some who aren’t happy the neighborhood is no longer a center for the black community.

“For these people, it’s the nostalgia that’s missing,” Arnold said. “They can’t recreate it easily, and it’s not the same with what they grew up with.”

Chaya Fletcher, the 34-year-old chef and owner of the Deep Deuce’s Urban Roots, has found a way to keep the spirit of the neighborhood’s history in her restaurant and entertainment venue. Housed in the former Ruby’s

Grill building, where Christian and other contemporaries performed, Urban Roots offers a variety of music, all of which Fletcher believes is honoring the district’s history. The owner, who comes from multiple generations that grew up around Deep Deuce, said her grandmother was pregnant with her mother while waitressing at the old Ruby’s Grill.

One music group performing every third Friday at Urban Roots is husband- and-wife duo Adam & Kizzie. Adam Ledbetter, an Oklahoma City native who attended Calvary Baptist, is using early jazz influences like Christian to inspire his modern sound.

“Whether we’re performing hip-hop, pop or another form, jazz is a strong underlying thread and informs all that we do,” Ledbetter said.

Starting last year, in celebration of Ellison’s 100th birthday, the production Ralph Ellison Understood Through Charlie Christian began traveling the state with Oklahoma City musician Walter Taylor’s TaylorMadeJazz group featuring Jake Miller playing Christian guitar pieces. The story of how the two men’s stories interact is performed with a narrative and music. The last show in the current tour was on Aug. 2 in Clearview.

Christian is a member of multiple state and national halls of fame. A street not far from downtown Oklahoma City, Charlie Christian Avenue, is named in his honor.

Print headline:

Play it again, Charlie

Charlie Christian’s legacy extends far beyond Oklahoma City, shaping the face of jazz — and, thus, all music — for many decades to come.