Major career retrospectives usually are earned by artists in their final years of activity, with catalogs spanning multiple decades, or those who have already left the confines of Earth and studio. But Harlem-based artist Kehinde Wiley’s work defies convention on so many levels that the 40-year-old artist’s large-scale, sociologically acute portraiture gets a career-spanning assessment with A New Republic through Sept. 10 at Oklahoma City Museum of Art (OKCMOA), 415 Couch Drive.

“It’s extremely unusual — it almost never happens,” said Michael Anderson, OKCMOA director of curatorial affairs. “So he’s pretty unique in that sense. He was able to go from a master’s art program and establish himself very quickly as an artist in Harlem in the early 2000s. This is an artist who is 40 now and is getting a career retrospective. It’s more like the beginning of a career retrospective because he has a lot of years ahead of him.”

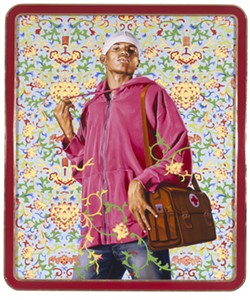

Reasons for Wiley’s quick rise in the art world aren’t hard to divine; his works are redolent of Baroque portraiture and often directly evoke masters ranging from Titian to Édouard Manet, but they are no mere pastiches. Wiley, who was born and raised in south-central Los Angeles before receiving his master’s degree in fine arts from Yale University in 2001, set up shop in Harlem in the early ’00s and developed an original methodology. He invited people off the street, mostly strangers wearing hoodies or warm-up suits, to come into his studio, thumb through art catalogues and select a heroic pose from antiquity.

Changing context

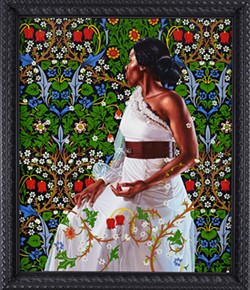

Beyond his immediately bracing skill at capturing nuanced emotions in his subjects, what comes across most effectively is the placement of young, African-American men and women in powerful contexts.

“My goal was to be able to paint illusionistically and master the technical aspects, but then to be able to fertilize that with great ideas,” Wiley wrote in an FAQ on his website. “I was trained to paint the body by copying the Old Master paintings, so in some weird way, this is a return to how I earned my chops — spending a lot of time at museums and staring at white flesh. If you look at my paintings, there’s something about lips, eyes and mucous membranes. Is it only about that? No. It asks, “What are these guys doing?’ They’re assuming the poses of colonial masters, the former bosses of the Old World.”

In the OKCMOA presentation of Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic, the seventh and final stop on a multi-year museum tour, Anderson said visitors will be struck first by the enormity of the works. These are canvases and stained-glass portraits that present almost like murals.

“He’s produced works that are over 35 feet long,” he said. “So these are enormous for oil-on-canvas works. But beyond their size and beyond their scale and scope of it, these are works that look like paintings that you are familiar with, so they look like works from the Dutch golden age, or Baroque painting or rococo works from the 18th century. They have a visual resemblance to something you’ve seen, but they have contemporary African-American males in the works.”

This approach is in full flower in Wiley’s “Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps” from 2005. Modeled closely on Jacques-Louis David’s 1801 “Napoleon Crossing the Alps” (or “Bonaparte at the St. Bernard Pass”), Wiley’s work is nearly identical to David’s original in posture and detail, except the horse’s rider is a goateed African-American man wearing a bandana, camouflage pants and Timberlands.

In later paintings collected in the World Stage section, Wiley took inspiration from art that is far afield from the European masters, pulling from Maoist propaganda and African sculpture, among other idioms. Then, for the Down series, he placed his subjects in repose or death depictions. For 2007’s “The Dead Christ in the Tomb,” Wiley used Hans Holbein the Younger’s 1521 Christ depiction as the template but posed a young man with a bicep tattoo wearing boxer briefs in the crypt. Beyond the race and modernity, Wiley’s dead Christ wears a surprised and fully alive expression on his face.

New frontiers

With his An Economy of Grace series, Wiley shifts toward female portraiture, offering an opportunity to expand his vision and pull the audience in new directions. For instance, his “Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness” (2013) depicts the biblical saint as an African-American woman with a striking shock of blond bangs.

Perhaps the most disarming works in A New Republic are Wiley’s stained-glass portraits. Despite the shift in medium, pieces like “Arms of Nicolas Ruterius, Bishop of Arras” are unmistakably the work of Wiley, a trick that the artist also masters with a series of sculpted busts included in the exhibit.

“He’s playing with religion and the question of who belongs in a stained-glass portrait,” Anderson said. “Those are the underlying questions: Who belongs on the wall of a museum? Who belongs in stained glass? Those are the core questions of his work, and he’s providing an original and provocative answer to those questions.”

Print headline: Fixing Baroque, Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic offers a socially, politically and religiously charged corrective to the European masters.