David Green and his family, owners of Oklahoma City-based Hobby Lobby, have been under investigation for four years for the “illicit importation of cultural heritage from Iraq,” according to The Daily Beast, which broke the story nationally in October.

In 2011, U.S. Customs seized over 200 clay tablets that were shipped from Israel to Oklahoma City. Their ultimate destination was Museum of the Bible, a facility funded by the Green family and slated to open in 2017 in Washington, D.C.

As the topic of cultural heritage rises to the center of public, political and legal discussion, many might not realize it has a long and labored history closer to home. While the Greens aren’t at the center of the debate over repatriation and preservation of Native American culture and relics, their case does illuminate the Native peoples’ long and labored struggle for the right to own and protect their ancestry and tribal sovereignty.

Born in El Reno in 1945, Suzan Shown Harjo is an activist, poet, writer and lecturer. She also is president of the Morning Star Institute, a Native American rights organization in Washington, D.C., and has helped shape the language of federal laws that now protect Native American culture and objects (“artifacts”) and the laws that mandate the repatriation of culturally sensitive items. In 2014, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award given in the United States, for her efforts.

As an expert on repatriation, she eloquently explains the different points of view on “archeology” or “grave robbing,” depending on how it’s interpreted.

The practice, she said, goes hand in hand with a dominate society that characterizes minorities as not being the true heirs to their ancestral culture, leaving culturally sensitive items up for grabs to steal and display in museums. While her concepts came about while hammering out laws regarding Native American rights, they are universal and can be applied to any culture worldwide where the heritage of a people is being taken from them for the benefit of a different culture.

‘Prisoners of war’

In 1967, Harjo attended a four-day meeting called by Cheyenne, Arapaho and Lakota religious leaders at Bear Butte, South Dakota. It concerned the dreams, visions and experiences people had in regard to getting back human remains, sacred objects, funereal objects and sensitive materials, or cultural patrimony, from museums and private collections.

It was the beginning of a long journey for Harjo, who was living in New York City at the time. In less than a decade, she would move to Washington, D.C., to lobby for what are now seen as historic laws to reverse late 19th- and early 20th-century policies that attempted to dismantle Native American culture.

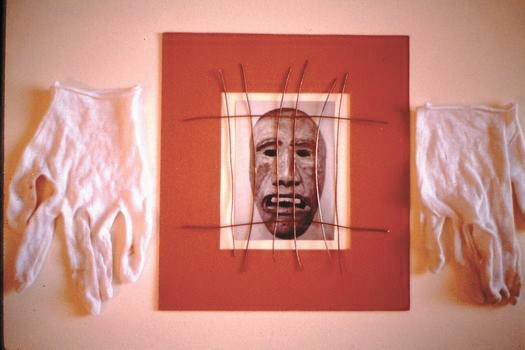

“The warriors, the combat veterans from Vietnam, gave us the image of our ancestors and our relatives being held as prisoners of war in these museums,” Harjo said during a recent Oklahoma Gazette interview. “It conveyed several things; we’re talking about people who are not dead, we’re talking about living beings, but we were also talking about sacred objects and other things — referred to as ‘materials’ in the museum world — that were being held against their will. These objects are also living beings; they were alive, and they are not dead, gone, buried nor forgotten. That was one of the reasons a lot of non-Native people thought it was okay to rob graves, whether it was called ‘archeology’ or it was just flat-out grave robbing — they believed it was OK to pillage and do all these things because the people were no longer living.

“That’s the same thing the powers that be in these holding repositories try to do internationally by separating the living people — the living Egyptians, the living Greeks, the living Italians, the legitimate people — from the ancient Egyptians, the ancient Greeks and the ancient Romans, as if that made a difference,” Harjo said.

She talked about the expatriation of Greece’s ancient and priceless marble statues by Ottoman Empire ambassador Thomas Bruce, also known as the 7th Earl of Elgin, in the early 1800s.

“And as if the modern Greek people had no say in getting back the Elgin Marbles,” she said, “Lord Elgin went from England to Greece, and before you knew it, parts of the Parthenon and other structures in Greece were in the British Museum, and they are still there, though the Greek government has consistently taken the position that they want them returned. The British had no claim to them, but they won’t entertain the notion of giving them back.”

Harjo sees it as a matter of semantics to say that the living descendants, such as the modern Egyptians, have no legitimate claim to the treasures of their ancestors. And this is applied to Native Americans — remnant bands and descendants are characterized as not being the “real” cultural bearers by those who want their cultural items.

“Another method is to say ‘Well, it’s art,’” Harjo said. “Because a leg bone was beaded and hung on someone’s wall, it is art, not a human remain.”

That interpretation, explained Harjo, justified the theft of the Zuni Indian war gods — wooden figures carved upon a person’s death and placed on that person’s grave to be taken by the elements — for example.

“They represent the journey of that person and their passage into the other world, so when the elements have taken the war god, you know that journey is completed,” Harjo said. “In the mid-1800s, non-Indians started taking the Zuni war gods. By the mid-1900s, those war gods were very valued items, not for their meaning, but as art, and because they were taken from graves. They were being sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars at Sotheby’s and Christie’s and all of the major auction houses.

“We had to overcome this general notion that today’s Native people are not the real Native people, who have ceased to exist, [and] that we are not the evidence of the cultural continuum. Therefore, there is no cultural continuum, and if you acknowledge that there is a cultural continuum, we are not the real beneficiaries of that, nor the owners of it. We have a lot of things to overcome.”

‘Reason in chaos’

Harjo said that out of that initial meeting in 1967, the group knew it needed a mandate to recover the human remains and items taken from Native American people, and if it had to be a law, it would be a law.

After compiling horror stories about different museums and agencies, the members looked around to see if anyone was doing it right, but Harjo said they found didn’t find anyone doing it right. That’s when the National Museum of the American Indian was brought up, to create a place that would do things in a sensitive way.

Harjo’s work would lead to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978. It serves to protect and preserve traditional religious and cultural practices of Native Americans.

A decade later, the 1989 National Museum of the American Indian Act created the framework for the Washington, D.C., museum and said the Smithsonian Institution must return all culturally sensitive items to federally recognized tribes.

Eleven months later, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was enacted. It called for all federal agencies and institutions that receive federal funding to return Native American cultural items, including human remains and funerary and sacred items.

It also deals with the inadvertent discovery of items during excavation and made it illegal to traffic in Native American human remains and cultural items obtained in violation of the act.

“We were trying to create streams of reason in this chaotic situation that had been created by grave robbers,” she said. “There’s one letter in the national anthropological archives that I keep coming back to when I think about these things. The army surgeon general had issued several army officers to go out and harvest Indian skulls. There are several … reports to the surgeon general to accompany the materials. One is from an army officer, where he wrote that he waited until the grieving family left the gravesite, exhumed the body and decapitated the head, ‘which [was] transmitted forthwith.’

“Now, if you unpack that, he watched this entire ceremony and the grief of the people and acknowledged it. Once the family left, he dug up the body, chopped the head off, [and] then he left out some steps: You measure the skull, weigh the brains, dump everything in lye and send the bleached skull, with your measurements, to the surgeon general,” she explained. “Imagine the family coming back to the grave and finding the person they had lovingly buried with his or her head gone.”

“Why did they chop our heads off?” was a question Harjo heard in virtually every meeting from 1967 until the final draft of NAGPRA in 1990. When they asked if there was a program that systematically called for collecting the heads of Indians, they received emphatic denials, but then letters about the policy were found in the Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Archives.

“In the middle to late 1800s, people thought how big the heads were was the answer to everything, or how many extra teeth they had,” Harjo said. “That passed for science. They gave up on the study of heads when the evidence proved that the French were not as bright as Cro-Magnon man; they decided it was a flawed study.

“What we were doing was not just revolutionizing museums and museum policy; we were bringing clarity to Native and non-Native people about what happened during that time. The history was being buried.”

‘Racially commodified’

While dealing with Native American rights and their bloody history, Harjo also deals with death threats regularly. She has been a vocal opponent to the use of Native American sports mascots. The lawsuit Pro-Football, Inc. v. Harjo brought about the cancellation of the Washington Redskin’s trademark with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Though that decision was overturned, a suit in which six other Native American plaintiffs challenged the federal trademark licenses of the Washington team, Blackhorse et al. v. Pro-Football, Inc. got the trademark canceled a second time in 2014. In 2015, the U.S. District Court in Alexandria, Virginia, upheld the decision.

“We don’t know who it is, but we assume that most of it has to do with the Washington football team,” Harjo said of the death threats. “Every time there is an advance in the litigation, we find there is an increase with those kinds of calls.”

The term “redskin” comes from the early days of white settlement on the continent, when trading companies, colonies and some states put a bounty on Native Americans.

“They offered a sliding scale — so much money for the men, so much for the women, so much for a child. Either you produced the whole body or you bring in their genitalia, because that’s how you tell the difference between and man, a woman and a child,” she said. “That’s the ‘redskin’ — the bloody, red skin. That is genteelly known as scalps; those were the ‘scalps.’”

Scalping was not just a Native American practice.

“There’s no other way to know what you are dealing with on the sliding scale, and there is nothing more racially commodifying than that,” Harjo said. “I don’t know how anyone can see that in any different light.”

Harjo is a fighter for Native American rights and a daughter of Oklahoma who has changed how Native American culture is dealt with in the United States. Receiving the highest honor in the land has only made her stronger in her quest for justice.

Print Headline: Reclaiming ancestry, An Oklahoma Gazette interview with Native American activist Suzan Shown Harjo sheds light on the struggle for the right to own and preserve cultural heritage.