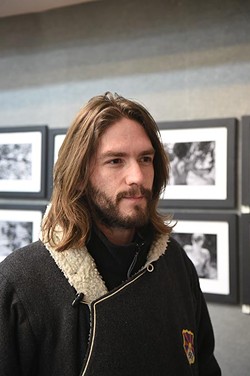

Yukon-born photographer David Joshua Jennings was living in a small village in Northern India, in the Himalayas, where a butoh master set up a school.

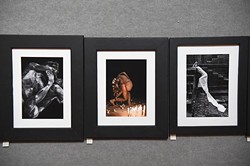

Jennings began photographing the dancers, gradually becoming more involved until he was shooting the artists across India. The result is his exhibition, Butoh, on display through Jan. 31 at Paseo Gallery One, 2927 Paseo St.

Butoh came about in 1959 in the Japanese avant-garde as a reaction to the growing, stern influences in dance at the time. Choreographer Tatsumi Hijikata conceived it as an outlaw form that subverted the traditional ideas of the craft that came before it, and he was against the idea of formalizing the genre; thus, there is no definition.

Even the term “butoh” is ironic, as it refers to elegant European ballroom dancing, yet it often deals with taboo and grotesque subject matter.

While Western ballet involves people jumping toward the sky, butoh is more earthbound, closer to the physical abilities of the common people. It connects with the ground. The energy, whether real or inspirational, is pulled up from the earth, which is the same reason sumo wrestlers stomp the floor before a match.

Inspired by European surrealism, dancers’ bodies are painted white and their choreography looks so strange to outsiders that it inspired the ghostly images in J-Horror, as in Hideo Nakata’s Ringu (1998) and Takashi Shimizu’s Ju-On: The Grudge (2002).

“It resists definition,” Jennings said. “An audience isn’t even necessary for butoh, and they would often go off and dance by themselves as kind of a meditation. That’s part of the philosophy of butoh; anything is a stage, anything is a costume.”

Poetic technique

Butoh was designed to be performed in obscure places, like a cave without an audience, or in public places normally not associated with street theater, such as skid row.

“Often, they are things that you stumble upon,” Jennings said. “They will perform in a public place without an announcement and the audience is just going about their day when they suddenly stumble upon this performance, which is kind of like a flash mob, but very different. It certainly disrupts someone if they are going about their normal life.”

The free form and lack of definition reflects Fluxus/Neo-Dada ideas of the American avant-garde, which developed at the same time in the U.S. and Europe, such as composer John Cage’s use of chance operations in music, where the sounds of the auditorium are as much a part of a piece as the notes that are written down.

“In some of the performances, when they perform in a theater, the audience is given noisemaking devices,” Jennings said. “The tempo of the noise being made, or any noise that is being made, can influence the dance, the co-body, which is a single dancer made up of multiple dancers reacting to each other and anything coming from the audience.”

For example, if they are performing in a theater and someone walks in during the middle of the dance, they react to that, he explained.

Becoming art

Like all art, adding an element of documentation impacts the performance, and this is especially true of butoh.

Jennings said the first time he photographed a group of dancers, no one spoke.

“Eight hours of dancing and no one talked to each other; they were all in this ‘butoh mood’ I guess you could call it, very concentrated,” he said. “It took a few times going out before I got to talk to any of them and ask how the camera being there affects them. We discussed that I had become a part of the dance. … The closer you get with the camera, the more intense it is because another human being is coming close to you and you can feel their energy.

“I would often start far away, taking pictures of them and the landscape, composing it to have their body interacting with the elements around them. Then I would approach,” he said. “The closer I got, the more intense it would be for both of us and for the images.”

Jennings said none of the images in the exhibition were posed or discussed ahead of time; he simply photographed dancers as they moved, often up to nine hours a day. He usually ended up with over 1,200 shots per session.

“It’s a real performance; it wasn’t staged for a camera. I wasn’t telling them what to do,” he said. “In most of the incidences, they would go out as a group and perform as part of their curriculum. I was just there.”

Jennings plans go back to India to shoot some more for a projected book, as each semester brings a new group of butoh students to the school. He also knows many dancers here in America that he hopes to photograph.

As a photographer, Jennings enjoys being part of the dance.

Print Headline: Chance creation, David Joshua Jennings’ Butoh photographs the undefinable.