The journey to restore safe water to Flint, Michigan, residents began this spring after a two-year battle between residents and government officials over dangerously high levels of lead found in the city’s drinking water.

More than a thousand miles away, an Oklahoma City University (OCU) professor used the crisis as his catalyst for teaching inorganic chemistry. In January, Stephen Prilliman began his upper-level science course by passing out copies of a Detroit Free Press article. It outlined the most recent response to the lead levels found in the Michigan city’s drinking water. Students quickly realized the situation was a scientific catastrophe.

“Everyone’s jaw dropped at the decisions that were made and the consequences of those actions,” Prilliman said. “We used this as a means to learn about chemistry, but I emphasized that we had to remember it was affecting real people’s lives. There are serious consequences of chemistry gone wrong.”

Flint’s water disaster was thrust into the national spotlight in January after President Barack Obama declared a state of emergency and endorsed using federal dollars to aid Flint’s recovery.

However, Flint residents knew the public health crisis was years in the making. The water troubles are easily traced to the decision by city leaders to switch to a new provider in an effort to cut costs. The move required building a new pipeline, meaning the Flint River became the interim water source until the added infrastructure was operational. Flint River water began flowing through taps and drinking fountains April 25, 2014. Corrosion controls were not required to treat the water.

Weeks later, the first wave of concerns were reported as residents complained about the water’s smell and color. After some time, E. coli and total coliform bacteria was detected, forcing residents to boil water and the city to increase chlorine levels in the Flint River. By early 2015, city officials warned water customers that Flint was in violation of the Safe Drinking Water Act, as high levels of total trihalomethanes (TTHM) also were discovered. A city test detected high lead levels in water at a resident’s home. A battle began as Flint residents fought to stop the poisoned water from flowing into their homes. The clash eventually lead to resignations by workers at the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality and regional Environmental Protection Agency, a congressional committee investigation and the state’s attorney general filing criminal charges in connection with the water crisis.

For residents, water filters and bottled water are the new norm until water returns to safe levels. Most tragically, the community is dealing with the outcome of elevated lead levels found amongst the city’s youngest residents.

Reactions, research

“There was a moment when I thought, ‘Oh my gosh. This is really happening,’” said OCU student Kelli Kortemeier. “They were really letting this happen to people.”

Other students shared her reaction. The outrage only intensified as they began their semester-long research assignment, part of the course requirement.

Prilliman instructed each student to select an area of the water crisis to study, such as the water’s chlorine levels, treatments for lead exposure or the effects of lead released from pipes. Through sources like scientific journals, news articles, government reports and data collected from a volunteer Virginia Tech University research team, the OCU students began forming their analysis.

Kortemeier and student Landan Beathard researched how chlorine impacted the oxidation of lead pipes. Basically, they wanted to understand the domino effect responsible for the contaminated water. Flint River’s high chloride levels caused lead to leach from the pipes, which contaminated water running into homes. The two reviewed independent scientific studies like the one conducted by Virginia Tech. Both were disturbed that government officials ignored indications of a problem found within independent studies. According to the EPA, when lead levels hit five parts per billion, there is cause for concern. The highest lead level found by researchers at Virginia Tech was 158 parts per billion, 30 times higher than the EPA number indicating unsafe amounts of lead. The data came from a water sample from a Flint home submitted in fall 2015.

Student Rachel Young examined lead, which is a chemical element with the symbol “Pb” on the periodic table. Young was aware of lead-based paint warnings and endorsed testing drinking water for lead; however, she wanted to understand what made the element so dangerous. Part of its danger results from its ability to mimic other metals that take part in biological processes and interact with many of the same enzymes. The science confirms lead exposure is unsafe.

“Before, this was something I only heard about,” Young said of her topic. “Now, I’m taking part and getting to the bottom of this problem. I have a better understanding of how much I’ve learned over the past four years. Before I came [to OCU], I wouldn’t have known how to do any of this.”

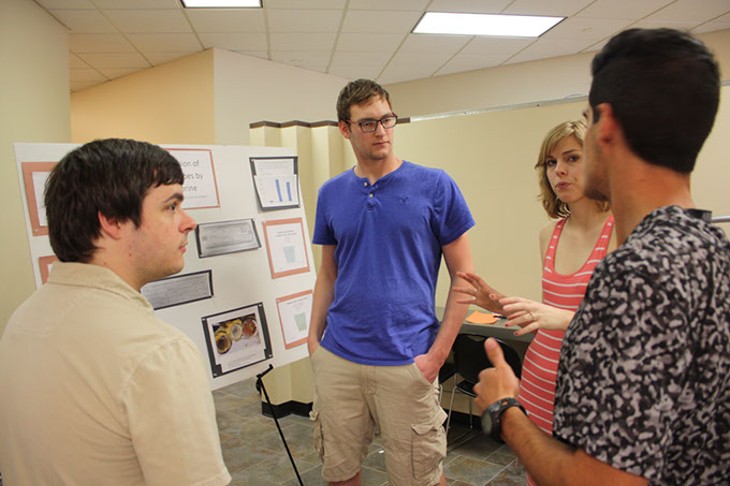

A week before the semester ended, students presented their findings to their peers. Prilliman advised them to explain their analyses in a scientific manner, but also be prepared to communicate findings to nonscientists. Their ability to communicate the science behind the evolving national news story became the professor’s proudest moment of the semester.

“This is such a valuable experience for the students as interpreters of sciences,” Prilliman said. “They are not just passive receivers, but able to interpret the science of others, informally and formally. … I’ve been very happy with the level of research. They all exceeded my knowledge within their own area. I learned a lot talking with them about their projects.”

Print headline: Impactful learning, Flint, Michigan, has been in the news since the recent discovery of very high levels of lead in its water supply. OCU students asked how the lead got there and if scientific findings could help avoid a similar crisis in the future.