On May 25, 1911, the lynching of a black woman and her teenage son six miles west of Woody Guthrie’s hometown of Okemah nearly erupted a race war with the neighboring all-black town of Boley. Tension escalated in Okfuskee County when George Loney, Okemah’s Caucasian deputy sheriff, was investigating stolen livestock and visited the black Nelson family’s farm near Paden, west of Boley, according to Joe Klein’s biography, “Woody Guthrie: A Life.”

A teen, Lawrence Nelson, thought the officer was going for his weapon and shot the deputy in the leg. Loney was refused water and bled to death, outraging whites. A posse formed to arrest the Nelson family, which was transported to the Okemah jail, according to Klein’s book. A week later, a mob of Okemah citizens transported Laura Nelson, Lawrence and her infant to a North Canadian River bridge west of town.

“The woman was raped by members of the mob before she was hanged,” The Associated Press reported.

Photographer George H. Farnum captured the image of two corpses dangling over the river as several dozen Caucasian onlookers posed on the bridge. After no one claimed the bodies, the two Nelsons were buried at nearby Greenleaf Cemetery. The elder Nelson went to prison, and the baby’s fate is unclear, according to conflicting reports.

The Okemah Ledger published the lynching photo, which became a reprinted postcard sold as a novelty item at local stores, Klein wrote.

Jim Allen, an Atlanta antique collector, discovered a gelatin silver print postcard more than two decades ago at a flea market. He now believes it’s the only photographed lynching of a female on record.

“People are shocked to find out that it is a woman, basically because the myth is that men were lynched because of raping white women or something like that when it’s not the case at all,” Allen said. “So to find a woman kind of debunks that myth.”

Allen featured the Okemah photo in the book “Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America” and at a Roth Horowitz Gallery exhibition in 2000. Five years later, Allen was speaking at The King Center in Atlanta when a black 25-year-old Oklahoma transplant approached him.

“She had just moved from Okemah where she had been raised, and she had never heard about the lynching,” Allen said.

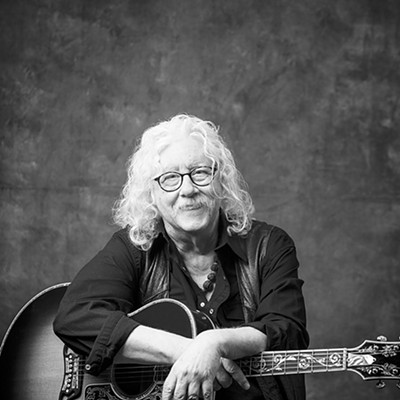

The 20-something apparently was not familiar with “Don’t Kill My Baby and My Son,” Guthrie’s lyrics published in a book compiled by Alan Lomax and transcribed and edited by Pete Seeger. In 1998, San Diego-based singer-songwriter Joel Rafael unearthed its obscure spirit during the inaugural set at the Woody Guthrie Folk Festival in Okemah. Rafael said Woody’s son, Arlo Guthrie, wasn’t familiar with the protest song’s lyrics, and some onlookers mistakenly assumed the Californian had written the tune.

“This song was pretty much buried in this book until I brought it out of hiding,” said Rafael, who discovered the lyrics decades ago. “People were pretty outraged.”

At the time of the Okemah

incident, such activity was not atypical. Lynching was Oklahoma’s most

openly exhibited variety of racial violence for its first two decades,

according to Jimmie Lewis Franklin’s “The Blacks in Oklahoma” book.

“Most whites, of course,

did not condone open violence, but many of them refused to speak out

against injustice,” Franklin wrote.

According

to Klein’s book, Guthrie’s father, Charley Guthrie, joined the posse

that arrested the Nelson family and the mob that dragged them to the

river. Woody Guthrie wasn’t born until 1912, but was his father present

at the incident?

“It’s

been stated that he was,” said Guy Logsdon, a Tulsa folklorist

considered a foremost Guthrie scholar. “I have not seen the evidence.”

Jim

Crow laws were enforced to keep blacks in their place, according to the

Final Report of the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of

1921.

“When Laura

Nelson was lynched years earlier in Okemah, it was not to punish her by

death,” the report stated. “It was to terrify the living. Why else would

the lynchers have taken (and printed and copied and posted and

distributed) that photograph of her hanging from the bridge, her little

boy dangling beside her?” A century later, the image is headed for

permanent exhibition at the National Center for Civil & Human Rights

in Atlanta, Allen said.

“There’s no way to redeem that kind of stuff,” Rafael said. “It’s so powerful and so dark.”

Woody Guthrie’s lyrics

Photo 1

Photo 2

“Don’t Kill My Baby and My Son” performed by Brooke Harvey.