bigstock.com

Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family perfected the art of medical marketing in the 1950s.

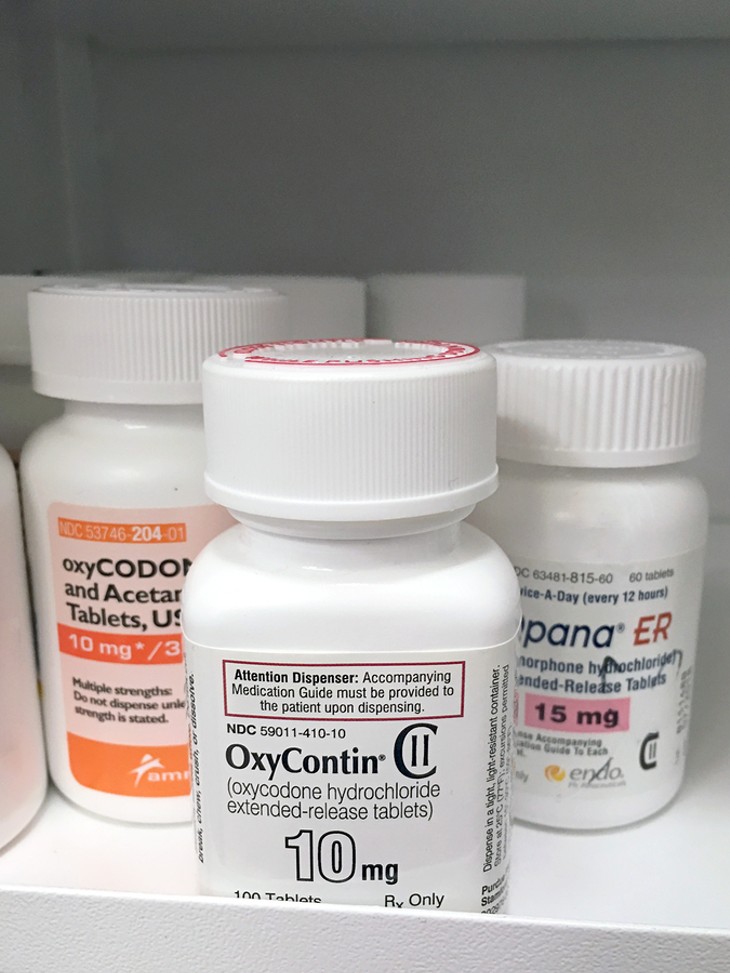

Since, humans have continually explored new ways to ingest the plant and use it for treatments, leading to everything from painkillers like Oxycontin or morphine to black tar heroin. These days, it seems common sense that opium, regardless of what form it is in, is not only highly potent but also highly addictive.

A study done by National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) cites Alexander the Great as one of the first major historical figures to have a documented record of addiction. He is said to have hastened his own death by heavy drinking, and Aristotle also noted in his writings the phenomenon of alcohol withdrawal and warned against drinking while pregnant. Though the word “addiction” did not become commonly used until the 1900s, the phenomenon was described by other names such as toxicomanie or inebriety.

Establishing a timeline of when and what we knew about addiction in relation to opium is much more complex. Opium can be distilled into many forms, and as new forms were discovered, they became more potent and were touted as being more pure.

In 1803, opium’s active ingredient was discovered through distillation and neutralization of the solution. That active ingredient became known as morphine — which was much more potent and fast-acting than powdered opium.

By 1843, the drug’s medicinal potential increased when it was discovered it could be administered by syringe, making the effects almost immediate and three times as potent.

C.R. Wright became the first to create an early form of heroin by boiling morphine over a stove in 1874, though it would not be commercialized until 1898.

Later in the 20th century, scientists would learn how to engineer opioids in a lab by mimicking the chemical structure of opium to create a class of drugs called “synthetic opioids.”

Opium-Eater

So how can today’s opioid epidemic be a product of doctors prescribing medication they thought to be of low risk for addiction?Given that we have known about the concept of addiction for thousands of years and have been cultivating and developing opium for even longer, at what point did we come to the conclusion that some derivatives of opioids are addictive and others are not? The history of opium addiction is essentially a game of two steps forward and one step back.

Opium has been used since the time of Hippocrates as an analgesic or pain reliever. Each step in the refinement process was thought to increase the potency, which it did, as well as decrease its addictive properties, which it did not.

When the active ingredient in opium, morphine, was discovered, it was hailed as “God’s own medicine,” as it was thought to be not only more potent and fast acting, but also safer to use and tamer than opium powder.

In 1821, an Englishman named Thomas de Quincey published a book in which he talked extensively about his personal struggle with addiction titled Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. Despite growing signs that opium was dangerous, it continued to be prescribed by doctors. Morphine was gradually found to be addictive, but soon after came the discovery of heroin.

Heroin was marketed extensively as a cure for many common ailments. It was produced commercially by German drug manufacturer Bayer, which advertised heroin as a remedy for everything from a child’s cough to pain associated with childbirth. Not only was the product marketed as non-addictive, it was promoted as a step-down cure for those suffering from morphine addiction.

The Saint James Society, an American charity organization, attempted to help those suffering from morphine addiction by providing them with free heroin through the mail. Some doctors at the time commented their patients seemed to be suffering from equal or greater withdrawal symptoms to that of morphine.

Opium would remain legal in the United States until 1905. Prescribing such drugs as medical treatment did not become illegal until 1923.

Although the attitude of restraint and caution when it came to prescribing opioids lasted until the 1990s, new advancements in medicine and marketing completely reversed this course by the turn of the century. From 1929 to 1968, prescription opioids were overseen by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN). When the first fully synthetic opioid was created, the FBN prohibited the practice of free samples for doctors, imposed prescription limits and screened all advertising to remove false claims such as low addiction rate. As a result, the drug was gradually incorporated into the market while maintaining safety standards.

Paradigm shift

This all changed with brothers Mortimer and Raymond Sackler and their descendants. If you are familiar with the name Sackler, it is likely due to their central role as owners of the pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma, which promoted the sale of opioids on a massive scale. But production of opioids was not their only role.In the 1950s, Arthur Sackler pioneered the concept of marketing to doctors. Trained in both psychiatry and marketing, Sackler was frustrated by the restrictions imposed by the FBN. An article published in 2019 by The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) quotes Sackler in 1957 saying, “There are fascinating case histories of wonderful medications inadequately used and only applied to a small percentage of those patients who require them.”

By 1957, Sackler had already radically changed the field of medicine by introducing aggressive marketing tactics. Internal sales documents from 1954 went so far as to describe doctors as “easy prey for [antibiotics].” The same article from NEJM described Sackler’s advertising campaign for an early antibiotic, saying, “The … marketing campaigns were conducted like military campaigns and described in the language of combat.”

The United States saw a fivefold increase in the amount of antibiotics prescribed between 1950 and 1956. This practice of overprescribing created high expectations among patients and would slowly cultivate the antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria causing public health issues today.

Arthur Sackler was even posthumously inducted into the Medical Advertising Hall of Fame in 1998, only two years after it was founded, along with the shining benediction, “No single individual did more to shape the character of medical advertising than the multi-talented Dr. Arthur Sackler. His seminal contribution was bringing the full power of advertising and promotion to pharmaceutical marketing.”

This chokehold on the drug market by the Sackler family — at this point three brothers all working in the field of psychiatry — was even investigated by U.S. Sen. Estes Kefauver, D-Tennessee. He and his staff were famous for investigating organized crime. Kefauver himself was chair of the Senate Special Committee on Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce in 1950 and 51.

According to Tufts Observer, though no charges were brought against the Sacklers, Kefauver noted in a staff memo, “The Sackler empire [was] a ‘completely integrated operation’ that could develop drugs, create favorable testing results, ghostwrite scientific journal articles, and directly advertise to doctors and the public.”

The suit was dropped in the 1960s, though at that point the Sacklers had already bought a small pharmaceutical manufacturer, Purdue Fredrick.

Purdue Fredrick was the company used throughout the 1970s and ’80s to promote the drug MS Contin, for which Purdue owned the patent. As the patent was set to expire, company executives looked at developing a new drug to market instead.

According to another article by the NCBI published in 2009, the new drug, Oxycontin, brought in $48 million in sales the first year it was on the market. Purdue later developed a fully synthetic opioid called Fentanyl that, according to National Institutes of Health, is anywhere from 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine.

Though its marketing tactics had been aggressive for decades, with the creation of the fully synthetic opioid Fentanyl in 1996, Purdue Pharma set out to create a complete paradigm shift.

To promote these drugs, which had a high abuse potential, Purdue Pharma and other drug companies had to find a way around the attitude of wariness and caution that came with prescribing opioid medication. To do this, they had to change the minds of doctors and scientists surrounding the nature of opioid medications.

In the early 1990s, opioids were used almost exclusively to treat cancer pain and other end-of-life care. In the early 2000s, they were being marketed for everything from joint pain to acute surgical recovery according to a 2019 article in NEJM.

By 2000, reports in scientific journals claimed the fear of prescribing opioids was overblown. This was termed “opiophobia” and became a critical tool for pharmaceutical companies when promoting the drugs.

A study conducted by Institute of Medicine (now National Academy of Medicine) in 1983 attempted to evaluate the potential use of cannabis as medicine. One of the potential benefits listed was as a potential treatment for opioid withdrawal syndrome. However, a follow-up study done by the same institution in 1999 reached a much different conclusion on the use of opioids in medicine.

“Such fears have proven unfounded; it is now recognized that fear of producing addicts through medical treatment resulted in needless suffering among patients with pain as physicians needlessly limited appropriate doses of medications,” the study said.

This was accompanied by similar studies from a variety of sources like Opiophobia as a barrier to treatment of pain published in 2002 and Randomized trial of oral morphine for chronic non-cancer pain, published in The Lancet, which found, “In patients with treatment-resistant chronic regional pain of soft-tissue or musculoskeletal origin, nine weeks of oral morphine in doses up to 120 mg daily may confer analgesic benefit with a low risk of addiction.”

These sudden shifts in dialogue were accompanied by other new developments in the pain care field, such as The Journal of Pain, established in 1990 to help doctors and psychiatrists determine effective treatments for pain. In 1996, the year the oral morphine study was published, Medical Advertising Hall of Fame was founded. Pain Care Forum, created in 2004, is another organization that provides advice to doctors treating pain in various forms.

Richard Sackler, nephew of Arthur Sackler and heir to the family business, began working at Purdue in 1971 as assistant to the president — his father, Raymond Sackler. In 1990, he was appointed to the board of directors, which he served on until 2018 along with eight other Sacklers, according to Financial Times. Richard Sackler was president of Purdue Pharma from 1999 until 2003.

His involvement in the company was the subject of a deposition brought by the attorney general of Kentucky in August 2015 that was leaked to ProPublica earlier this year.

The deposition is roughly 560 pages long and contains excerpts from various speeches Richard Sackler gave, including one just after the launch of Oxycontin.

“This didn’t just happen,” Sackler said. “It was a deftly coordinated, planned event that took dozens of workers years of effort to succeed. The most demanding new drug approval package for an analgesic ever submitted didn’t languish at the agency. Unlike the years that other filings linger at the FDA, this product was approved in 11 months, 14 days. Our previous best approval time was measured in years, not months.”

The Sackler family vigorously denies any link to the current opioid epidemic.

It took a long time to fully realize the negative consequences of opium and other narcotics. Opioids do certainly have a role in pain management and have had for thousands of years. We as a species have slowly but surely arrived at the definitive conclusion that opiates are addictive — until the Sacklers decided they were not.