Bob Ingersoll has rescued primates from bad conditions and looming executions to place them in sanctuaries, but his dream is for those very sanctuaries to go out of business. Sanctuaries provide lifetime care for primates raised in captivity because they lack basic wilderness survival skills.

“You can’t just bring these animals back to the wild. It just wouldn’t work,” he said. “It’s very difficult to undo the damage we’ve already done. As best we can, we integrate them in with other chimps. We try to give them as many choices as we can and make those choices meaningful to them.”

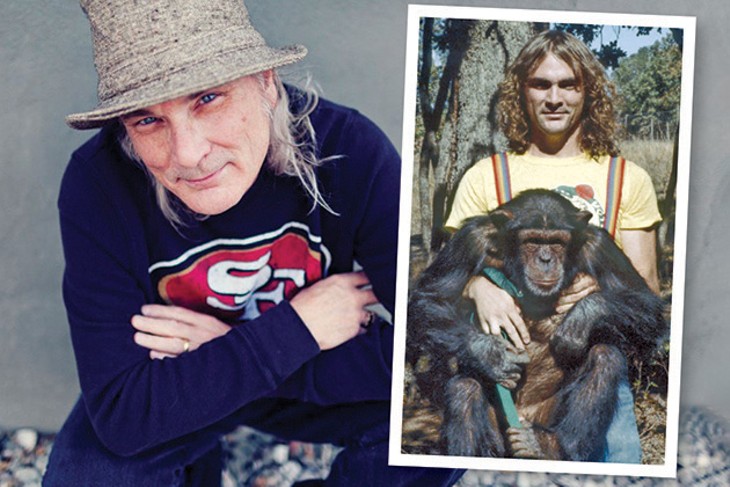

Ingersoll has worked with and helped rescue hundreds of primates since 1975 when he was a student at University of Oklahoma. He even appeared in Project Nim, a documentary that chronicles a research project based around determining whether a chimp could be raised as a human and learn sign language.

“In the last 40 years, things philosophically have changed in terms of how we not only just treat primates — chimpanzees in particular — but all animals,” he said.

Today, Ingersoll serves on advisory boards for various primate sanctuaries in and out of state including Center for Great Apes in Florida, which he calls “the gold standard for sanctuaries.”

“We built almost a half a million dollar new night house and outside enclosure, which I’ve seen and I’ve seen them all in. It’s just incredible,” he said. “It’s a phenomenal facility. It’s not the wild, and unfortunately captivity is what it is. Once chimps are in captivity, they’re pretty much stuck, and that’s a shame. … We don’t breed. We don’t perpetuate the problem, so to speak. Ultimately, what we want to do is put ourselves out of business, but unfortunately, that’s not going to happen in my lifetime because chimps live for 50 or 60 years. These chimps deserve our support and our financial support is what keeps the center going.”

Animal rights

Center for Great Apes cares for about six Oklahoman chimpanzees, some of whom were rescued from Arbuckle Wilderness and Joe Exotic’s Greater Wynnewood Exotic Animal Park.

“Two chimps, whose names are Bo and Joe … were just recently acquired from Arbuckle Wilderness, and their brother is also there,” Ingersoll said. “His name is Murray. He’s also from Oklahoma, and he was acquired through a convoluted path before he ended up at Center for Great Apes.”

Murray was born and lived at Arbuckle Wilderness and was predominantly used as an attraction for the park, Ingersoll said. One day, Murray bit a child, which caused officials to file an execution order for Murray to test him for rabies. But Ingersoll and other experts convinced them to avert the order. Instead, Murray was sold various times before he ended up as a couple’s pet.

“It’s embarrassing that humans care so little about something so important.”

tweet this

—Bob Ingersoll

“They had Murray for a number of years, along with another female chimp, but they came to the realization that, ‘Wow, this is really wrong.’ That’s how Murray ended up at the Center for Great Apes,” Ingersoll said. “Murray is now thriving there and has been for at least 10 years, and he and I are pretty good friends. I can tell you straight up that he’s one of the coolest chimps I’ve ever met. He’s a joy to be around.”

But the biggest feather in Ingersoll’s cap, he said, was helping Dr. James Mahoney get more than a hundred chimps out of the Laboratory for Experimental Medicine and Surgery in Primates.

“We got 109 out. It took us two years to plan it and to make it happen. I didn’t do that much. I introduced him to the people he needed to be introduced to and the sanctuary directors,” Ingersoll said. “To me, that’s the crown jewel on my career because I was able to help a lab guy pretty much steal 109 chimps out of a lab.”

After developing a reputation for helping primates and some monkeys, Ingersoll said he now gets approached often by people who have the animals as pets and want to place them in better conditions.

“It’s a real problem because people see imagery of people dressing up monkeys or holding chimps and they assume that it’s cool, but it’s anything but cool,” he said. “Besides being extremely dangerous, they have needs that go far beyond a human infant. When you deprive them of their right to be what they are, then you impose yourself on their lives, and you have to take care of everything. I just don’t think people realize that or, for the most part, I think they wouldn’t do it.”

Ingersoll calls himself an animal rights activist but said he doesn’t take an all-or-nothing approach with his activism, instead opting for compromise to help as many individual animals as possible.

“There needs to be some sort of national legislation to ban the breeding of non-human primates in a non-sanctuary setting or a non-zoo setting, which I’m not for breeding at all, but you can make some compromises in order to get something good done,” he said. “We’ve got to slowly change. Our culture is changing. We’re slowly moving in a direction I think is positive, but I don’t think it’s wise for anybody to draw a line in the sand and say, ‘It’s either this way or the highway.’”

At the same time, Ingersoll said people should be more cognizant and willing to speak out for animal rights, which interconnect with other environmental concerns.

“You can’t save the forest without saving the animals, without helping the people that live underneath those trees,” he said. “Humans and animals ought to be considered at the same time. … The planet is not going to be able to sustain itself. I mean, several species of great apes — orangs and chimpanzees and gorillas now — are on critically endangered list. That doesn’t bode well for us in the long run. It’s embarrassing that humans care so little about something so important. Those are our closest relatives in the animal kingdom. We can’t even protect them, never mind the elephants and all the other animals.”

World Wild Life’s 2018 Living Planet Report found that populations of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles and amphibians have declined by 60 percent in just over 40 years. A 2019 study in the journal Biological Conservation found that more than 40 percent of insects species are also in decline.

“To me, it’s criminal, but I pay close attention to these things,” Ingersoll said. “I’m affected by them deeply because I know animals personally. They’re my friends. Murray and Bo and Joe and all the chimps and orangs that live at the Center for Great Apes, I know them personally. I know their personalities. I also know their caregivers. Supporting those caregivers and the work they do is critical. This work is very important.”

Ingersoll said his philosophy on animal rights has evolved, but his dedication to helping animals is stronger than ever. He credits much of his career to working with the chimps learning sign language at University of Oklahoma in the ’70s.

“I want to honor their legacy and their memory by doing everything I can to help their brothers and sisters,” he said. “It makes no sense not to speak up. This is no personal attack on anyone; it’s an attack on all of us. We’re all responsible, every one of us.”

Ingersoll said there are also various local sanctuaries people can support, including Oliver and Friends Farm Sanctuary in Luther and Oklahoma Primate Sanctuary in Oklahoma City. He said if people can’t support the facilities financially, they can still share their social media posts or spread the word.

Visit centerforgreatapes.org.