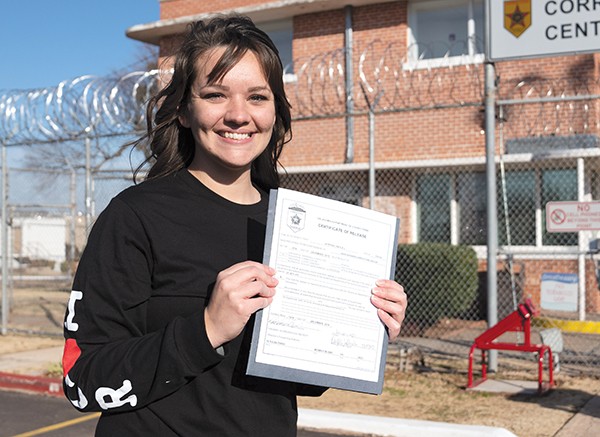

She has been called the face of a movement. Twenty-six-year-old Kayla Jo Jeffries stepped out of prison on Dec. 5 a free woman, thanks to a commutation declaration that was signed by Gov. Mary Fallin the same day. Smiling from ear from ear, release papers in hand and holding back tears of joy, Jeffries told reporters the first thing she wanted to do with her freedom was hold her children.

“It’s been a really crazy week. I have a wonderful support system that helped me get back on my feet in a lot of practical ways. I was able to get my driver’s license back, a car ... I even have a job. But in other ways, it’s been kind of overwhelming. Going into Walmart for the first time again was bad,” Jeffries said with a laugh. “I don’t want to go so far as to say that prison institutionalizes people, but I have been so used to someone telling me when to eat, sleep and socialize even, that it’s taking me some time to adjust to my freedom.”

Jeffries, who was sentenced to 20 years behind bars for possession of methamphetamine, earned a cosmetology license while in prison that helped her get a job her first week out.

She said she’s grateful for her lawyer, Glen Blake, members of Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform, law school students from University of Tulsa, Gov. Fallin and all Oklahomans who voted yes on State Question 780 two years ago.

“I remember reading in prison that the law would not be retroactive,” Jeffries said. “That stung a little, but I was still happy for those who it would affect moving forward.”

Jeffries had no idea, she said, that through the process of commutation, where a judicial sentence is reduced, her own 20-year prison sentence would be completely cleared two years later.

Crisis mode

If the plethora of internal violence and drug abuse cases weren’t enough to indicate that a crisis had been brewing within Oklahoma’s nearly 30 prisons for decades, a damning statistic from the nonprofit think tank organization The Prison Policy Initiative made it clear.This year, the organization revealed that Oklahoma is ranked first in the nation for the number of people incarcerated.

“America incarcerates more people than any other nation in the world, and Oklahoma incarcerates more people than any other state in the nation,” Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform chief of staff John Estus said. “Basically, right here in this state, more people are in prison than in any other place in the entire world.”

In response to several concerns, one being overcrowding within Oklahoma’s prisons, Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform organized a statewide initiative to pass State Questions 780 and 781 in Nov. 2016.

SQ780, also known as The Oklahoma Reclassification of Some Drugs and Property Crimes as Misdemeanors Initiative, lowered the charges of certain nonviolent drug- and theft-related crimes from felonies to misdemeanors, which carry a maximum penalty of a one-year prison sentence and a $1,000 fine.

“It took us 30 to 40 years to get in this mess. It’s going to take us more than a year or two to get out.” — John Estus

tweet this

The law would, in effect, make drug possession a misdemeanor and theft of items totaling less than $1,000 in value a misdemeanor as well.

Provided that SQ780 would pass, SQ781 would allocate the funds saved by the initiative to privately run rehabilitation facilities where drug users could gain mental health and substance abuse treatment along with job training and education.

Supporters of the state question said it would reduce overcrowding in the state’s prisons, save taxpayers money and allow drug abusers access to treatment that would likely prove more successful than what they would otherwise receive behind bars.

“One in three people in Oklahoma’s prisons need mental health treatment, and one quarter of inmates are serving time for a nonviolent drug offense,” Kris Steele, former Republican house speaker and current chairman of Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform, said. “It is time to take a smarter approach to public safety by increasing access to programs that address the root cause of crime.”

By contrast, opponents of the state question argued that criminal drug abusers should be separated from law-abiding citizens in the case that such offenders turn violent.

“I will have a conversation with a family about a guy who has been six times in the county jail for meth, and then he kills somebody. And I will have to tell them, ‘If the law hadn’t changed, I could have stopped this guy,’” Cleveland County district attorney Greg Mashburn said.

Jeffries said from personal experience she knows that drug abuse rarely ceases in prison.

“I saw more drugs in prison than I had ever seen when I was out of prison,” she said.

Jeffries first saw heroin as an inmate in one of Oklahoma’s prisons.

Having been off drugs for years now, Jeffries said it was her newfound faith and not any kind of treatment program that launched her path toward sobriety while she was an inmate.

On Nov. 8, 2016, State Questions 780 and 781 passed with 58.23 percent of voters casting ballots for the measure and 41.77 percent voting against it.

While the new laws applied only to current and future offenders, Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform began a behind-the-scenes movement that would grant justice for the previously accused.

Unfinished business

Project Commutation is Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform’s newly titled initiative to grant commutation for the over 1,000 inmates behind bars who would not currently be there had State Question 780 been in effect when they were arrested.University of Tulsa law student Sarah McManes said she was one of about 30 law students from the school who helped review the cases of over 700 inmates eligible for commutation.

“This process was completed in a matter of months, but we spent thousands of hours working on these cases during those months,” McManes said.

Twenty-one of the 700 inmates considered for commutation were granted their requests by Fallin on Dec. 5.

“As we prepare for the Christmas holiday season,” Fallin said with tears in her eyes during a press conference, “let’s not forget there is a God of second chances.”

Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board granted an additional nine inmates commutation recommendations on Dec. 12 and expects Fallin to grant or deny those requests before her last day in office in early January.

A remaining injustice, Estus said, is that for now, those granted commutation receive their reduced sentences with felony charges remaining on their records.

“Life with a felony is hard,” he said. “A felony charge can determine whether or not these newly released individuals can gain employment, enroll in school, get a car and a home.”

Estus said he’d like to see Oklahoma’s Legislature enact a policy that would allow free expungement, or the sealing of convictions, to those granted commutation. With attorney fees included, an expungement in Oklahoma can cost as much as $1,000.

Estus said the granting of recent commutations is just the tip of the iceberg toward criminal justice reform in Oklahoma.

“It took us 30 to 40 years to get in this mess,” he said. “It’s going to take us more than a year or two to get out.”