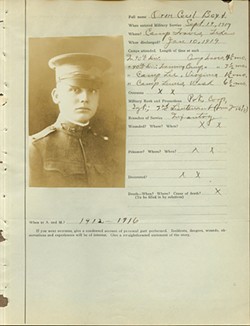

Before he was killed in action in Northern France on July 4, 1916, American poet Alan Seeger wrote:

Drink sometimes, you whose footsteps yet may tread

The undisturbed, delightful paths of Earth,

To those whose blood, in pious duty shed,

Hallows the soil where that same wine had birth.

But Michael R. Grauer, the McCasland curator of cowboy culture at National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, said few these days remember the soldiers who fought the Great War, though many who served were their great-grandfathers or great-uncles. Even in the years immediately following the war, few wanted to remember the horrors of the unprecedented global conflict.

“Everybody wants to forget it,” Grauer said. “No one was prepared for the gruesomeness of World War I, high explosive shells and chemical warfare on a scale nobody ever imagined. … Unfortunately, World War I is the forgotten war, absolutely forgotten. There is no national monument in Washington, D.C. for World War I, for example. We lost more men in a relatively short amount of time than in any other war. … Nobody understood the tactics. Nobody understood a machine gun or chemical warfare.”

The National World War I Memorial is still under construction in Washington, D.C., but Cowboys in Khaki: Westerners in the Great War — on display at National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, 1700 NE 63rd St., through May 12, 2019 — chronicles the efforts and sacrifices people from the western United States made to help the Allies win WWI. Grauer said farmers and ranchers began these efforts prior to the U.S. officially entering the war in 1917 by providing beef and wheat to Belgium and France, which became increasingly crucial as the war progressed.

Many men from the western United States also went to Europe to fight. While some cowboys went to Canada to enlist before the U.S. officially entered the war, many more joined or were drafted into the U.S. military after the country officially declared war on Germany. Just two generations removed from the Civil War, soldiers from the former Confederacy had a chance to show their loyalty to the re-United States.

“World War I provided an opportunity for Southerners to become Americans again,” Grauer said. “This was 50 years later, and it was an opportunity for a true reunification to happen because of the Great War. You could prove yourself to once again be an American by Great War service.”

However, that didn’t mean these cowboys and farmers were ready to give up their individual identities.

“The political climate was, yeah, they wanted to be in on it but they wanted to kind of maintain their own regional diversity,” Grauer said. “I think there’s a certain amount of independence in the Westerners. They were notoriously rebellious against rule and against officers, and so making them a cohesive unit was a real challenge because they didn’t like taking orders. Farmers in particular because usually a farmer is independent, whereas a cowboy usually was part of a crew and he got used to having a wagon boss. But cowboys and farmers really resisted their officers, especially if they came from another part of the country. So if you had Yankee officers, for example, trying to press their will upon their men, then it usually didn’t work too well.”

Troops from the Texas and Oklahoma National Guards formed the 36th and 90th infantry divisions, also known, respectively, as the T-Patchers and the TOs (or Tough Ombres) due to the insignias on their uniforms. Cowboys in Khaki features artifacts from the museum’s military, rodeo and history collections as well as loans from 45th Infantry Division Museum in Oklahoma City and Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon, Texas, to illustrate their histories.

While Western soldiers fought to maintain their regional identities, Europeans at the time viewed Americans and Westerners as “interchangeable and indivisible,” an idea that was reinforced by the U.S. Army’s uniforms at the time.

“When US troops debarked the boats in France, they’re all wearing campaign hats which we call ‘Smokey Bear hats’ today,” Grauer said. “And the French civilians, when they first see them getting off the boat, they see them as all wearing cowboy hats, chapeaux de cowboy. In other words, the cowboys are here to save the day. … Everybody in Europe and other parts of the world thinks every American wears a cowboy hat. So that confirmed it when they got off the boats in France in 1917.”

Forgotten heroes

Native Americans, who wouldn’t officially be recognized as U.S. citizens until 1924, also played a significant role in the war effort.

“Here in Oklahoma, for example, people are familiar with the Navajo code talkers in World War II, but in fact, the code talkers started in World War I, and they were Choctaw,” Grauer said. “They fought with distinction and valor, earning meritorious medals.”

Many troops completed artillery exercises at Fort Sill in Lawton, though the army post was significantly less equipped for training at the time.

“We sent troops to Fort Sill who were training on one cannon because they only had one,” Grauer said. “A lot of time, their training was with sewer pipes or tree stumps and all kinds of stuff because they were totally unprepared to go to war.”

Horses also played a vital role in an era when motor vehicles were much more rare.

“Something like 8 million horses saw service,” Grauer said, “not just for the U.S. but for all forces on all sides, and the life expectancy for a horse or a mule in World War I was 10 days. They were targets because that was the only way to get the wagons around.”

While many have forgotten the stories of World War I, its ramifications continue to define the boundaries, alliances and conflicts in the modern world.

“We’re still fighting World War I,” Grauer said. “It never ended. Everything that’s happening in the world today is a direct result of what was left unfinished at the end of World War I.”

The last living WWI veteran died in 2012 at the age of 110, but in the U.S., the end of the war is still commemorated on Nov. 11 as Veteran’s Day, originally called Armistice Day.

“I heard a speaker on World War I say, ‘There’s no one who’s truly missing in action unless they’re forgotten,’” Grauer said. “Part of the National Cowboy Museum’s effort is to make sure those men and women are not forgotten.”

Visit nationalcowboymuseum.org.