The door to a south Oklahoma City low-budget motel room opened. Officer Clint Music looked past a woman who stood a few feet away. Instead, his gaze was fixed on a man sitting on the bed, his back turned to the door.

Investigating a reported kidnapping and looking for a man called Catfish, Music had just enough time to ask for his name before the man stood and fired a pistol.

Music jumped back from the doorway, raised his gun and returned fire.

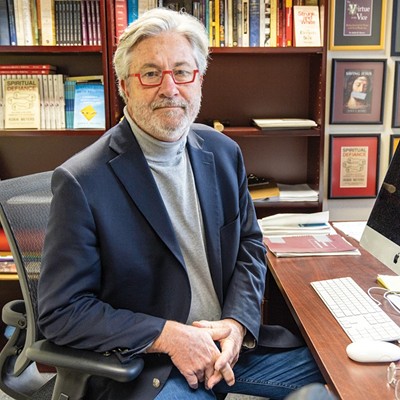

The Oct. 8, 2014, shootout resulted in an injured officer, the death of a victim held captive in the room and an investigation into the officer’s actions. Music’s decision to pull his gun in two seconds was scrutinized for two months by homicide detectives, internal affairs officers and the Oklahoma County district attorney, all of which decided he acted appropriately. A team of police majors and a citizen committee that looks over all uses of force by OKC police officers also reviewed the case.

In recent months, national events ignited concern over the use of police force after a string of incidents left young men dead at the hands of law enforcement. Some wondered about police who might use inappropriate force.

A review of dozens of reports on OKC officers who used batons, Tasers, pepper spray, their fists or a firearm shows challenges officers face when making split-second decisions while confronting potentially violent individuals. These reports also highlight the detailed policies officers must follow when using force, along with the individual discretion they must make based on a rapid series of events.

Simulator

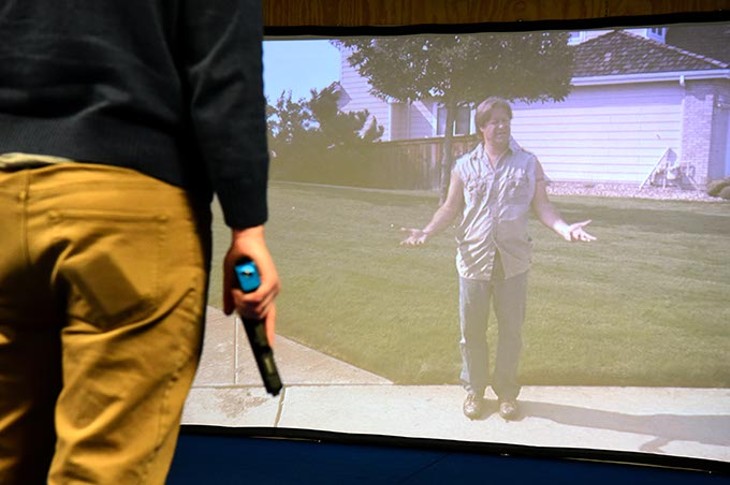

The shooting simulator at the Police Training Center doesn’t feel like real life until the lights are dimmed and a giant screen displays a life-size video of a typical police scenario.This particular scenario is a domestic disturbance call. As the simulation participant approaches the house, a neighbor says the couple’s fights have grown in recent weeks. A suitcase sits on the front step, the front door is open and someone inside is yelling. While walking into the house, it’s clear that the man yelling in the living room also holds a shotgun in his lap.

Is he cleaning the gun? Is he packing it to leave? Maybe he is planning to harm the woman.

Three seconds pass before the man raises his shotgun, forcing the participant to raise his simulated firearm to return fire. The speed in doing so decides whether the man with the gun survives or whether the trainee does.

“We don’t dictate the amount of force we are going to use; the suspect does,” said Sgt. Travis Serna, a self-defense instructor with the department. “But you have to be prepared for everything.”

Police policy restricts the use of force to a response of the suspect’s actions. For example, a gun might not be appropriate to use on a man swinging his fists, and a baton is not appropriate to use on a suspect with an automatic weapon.

Officers are trained to use a variety of options, including a gun, when responding to a suspect. Some police officers admit that in a fight with a suspect, they often resort to the use of near-automatic muscle memory, deploying a series of rehearsed moves. Also, some officers admit they are conditioned never to carry anything in their right hands, even groceries, a reminder of their academy training.

While most calls an officer responds to lack violence, the police training center simulator shows how quickly a situation can escalate and why officers approach each situation knowing that force could quickly become an option.

While the Oklahoma City Police Department adopts detailed definitions and regulations concerning the use of a firearm or other use of force, the office also has a lot of discretion. “Reasonableness” is a word used in the department’s operations manual as the bar for when an officer is justified in shooting a weapon.

Accountability

Today’s camera phone era provides numerous examples of police using force in ways that invite public scrutiny. Breaking down information by department gives a more accurate picture of when and why force is used than lumping together random nationwide events. The reality is each situation is unique, and police officials also point out that each department is different.Last year, a dash cam recorded South Carolina State Trooper Sean Groubert shooting Levar Edward Jones after he reached into his car to retrieve his license. In the video, Groubert asked Jones to produce his license and then opened fire when Jones reached back into his car.

Groubert was arrested and charged for the shooting. Last year also saw the death of a New York City man after police put him in a chokehold. The video captured the entire incident, and a grand jury recommended against filing charges.

Closer to home, examination of instances of police force resulted in exoneration, commendation and jail time. Last year, cell phone video captured three Norman officers holding a man down who was screaming for help. Like many videos of police force, some called what they saw in the footage excessive, and the Norman Police Department investigated.

“Although any use of force above the levels of command presence and verbal direction may be viewed unfavorably by some, it is necessary in order to gain and maintain control of noncompliant subjects,” Norman Police Chief Keith Humphrey said following the determination that the three officers operated according to guidelines.In another case, a Del City officer who killed an unarmed teenager in 2012 was convicted last year and sentenced to four years in prison.

“The majority, I mean, vast majority of law enforcement officers in this country and this state and this city are outstanding professionals,” said District Attorney David Prater following the verdict, also noting that he believed the majority of officers do “everything right” when firing their weapon. “[But] when officers cross the line, they’ll be held accountable, and we will police our own.”

National incidents over the past year have raised the idea of body cameras for police, and City Manager Jim Couch said a report on the cost and feasibility of using body cameras in OKC will be presented this year. Until body cameras are used, or unless a bystander or security camera picks up the footage, witness accounts and a review process that considers whether or not an officer followed protocol are used to investigate police shootings.

The OKC police department recorded 605 uses of force last year, which ranges from physically holding down a suspect to firing a weapon. Of those incidents, 15 were deemed an inappropriate use of force.

“That could mean too much force or not enough force,” said Captain Juan Balderrama with the department’s public information office.

Examples of officers disregarding rules and abusing their position of power can be found, as is the case in most every profession. However, the training, policies, review process and detailed reports that are filed following each incident of force demonstrate the training, critique and quick judgment that goes into each situation in which force is required.

Print headline: Forceful decision, It takes professionalism and quick judgment when an officer decides to use force in a situation, but is it enough?