An hour after midnight on Feb. 25, 1910, police officer Morris Reagan stood watch over his quiet northside beat in Oklahoma City. Only the full moon overhead offered him any companionship as he patrolled alone in the brutal cold.

In 1910, Oklahoma City was a town of about 64,000 people. Yet, in the newspapers, a new murder or robbery splashed across the headlines daily. That morning’s paper would be no different.

Homeward bound

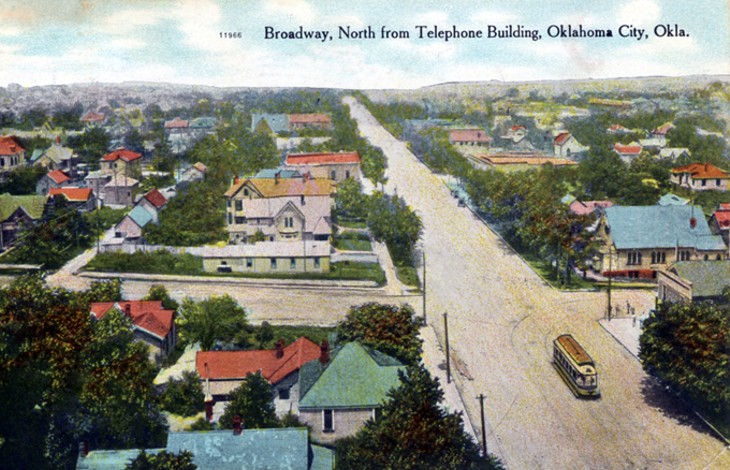

Around 1 a.m., Dr. John Riley was heading home after working late at St. Anthony Hospital, where he had been attending a man shot by police earlier that day. As he made his way toward his home at 1302 N. Broadway Ave., he passed the still-standing Cadillac Building near the intersection of 10th Street and Broadway. There, he noticed Officer Reagan questioning a black male wearing a dark overcoat and a white scarf. A few moments later, Dr. Riley would be tending to his second gunshot victim of the night.

As Riley was parking in his garage, a loud gunshot pierced the quiet neighborhood. Riley raced back to the intersection where he found Officer Reagan lying facedown on Broadway with a hole in his forehead. Although still alive, Dr. Riley could see that it was a hopeless case and that Reagan was “in the arms of death.”

He ran to a nearby residence and roused the occupants in order to use their phone.

Oklahoma City Police Department had not had an officer killed in the line of duty for 12 years. When the call came into police headquarters, everyone was stunned.

Assistant Chief Joe Burnett and several detectives jumped into a police buggy and headed north on Broadway. As they galloped past Fourth Street, Officer Braun noticed a black man briskly walking south. Braun immediately halted the buggy and detained him.

The man, whose name was Will Martin, was wearing a heavy coat and scarf and was walking in a direction away from where the murder had taken place. That made him the prime suspect.

Stunned, Martin explained that he was heading downtown from his room near Seventh Street and Broadway in search of a drink. Furthermore, he asked what wardrobe and speed of pace should be expected on a cold night where the temperature was only around 10 degrees.

Unpersuaded, the police transported him to the crime scene, where Dr. Riley identified him as the man he saw being questioned by Officer Reagan.

Martin was then hauled to the police station and given a “severe cross-examination” by Chief of Detectives Shirley Dyer. Police boasted to reporters that a full confession was expected.

A confession

Yet, despite the best efforts of Dyer and the accusatory finger of Dr. Riley, who directly confronted Martin at police headquarters, telling him, “The man that killed Reagan wore a white scarf, and you have one on!” Martin would not confess and insisted that he was innocent.

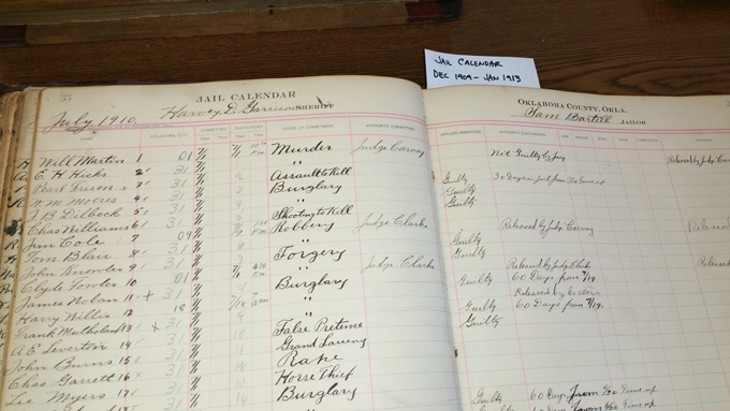

Outside, a crowd of angry citizens began to form. Fearing vigilantes, the police called in reinforcements and transferred Martin to the Oklahoma County Jail, where he was booked for murder.

Martin reportedly wept and prayed in his cell and was placed on suicide watch.

In 1910, justice was hard to find if you were black, especially in the Jim Crow-era South. The presumption of innocence was little more than an empty slogan if you were accused of a crime against a white person.

Often, the accused were lynched before they could ever reach trial. And if a trial did take place, guilty verdicts were routinely rubber-stamped by all-white juries who did not want to risk the social implications of siding against other whites.

That’s what makes the case of Will Martin such a rarity.

Police desperately searched for the murder weapon in the hours that followed the shooting. Despite an “unrelenting search where police scoured thoroughly” every inch of Broadway and Robinson Avenue, looking for the discarded revolver, it wasn’t found.

Nevertheless, in the days that followed, evidence against Martin began to mount. A fellow police officer named James Rippey claimed that he had seen Reagan search Martin for weapons in the past and had overheard Martin threaten to kill Reagan if he bothered him again.

Another officer named Veasey claimed that Reagan told him, “A nigger named Martin was looking for him with the intent to shoot him” and sought his advice in purchasing a better gun to protect himself.

The noose was quickly tightening around Martin’s neck.

Reagan family

Morris W. Reagan, the murdered officer, was a native of Texas and a man of the law for many years in various parts of the state before joining the Oklahoma City Police Department just three months before his death. He was 49 and was married with two small children.

Reagan came from a highly respected Southern family. His father, William Reagan, was a retired lawyer and magistrate. His brother Thomas was a former police officer himself and had only recently quit to join the fire department.

However, Officer Reagan’s most interesting relative was his uncle John H. Reagan, the Postmaster General of the Confederacy during the Civil War. Before his passing in 1905, he was the last surviving member of the Confederate government. Local sympathy was high for this family.

The accused

On the other hand, not much is known about Will Martin. His age and personal details are never mentioned in contemporary accounts, but it is known that for several years, he worked as a porter at the Threadgill Hotel on Broadway. While there, he had acquired a very good reputation among the management and other porters he worked with.

When the head clerk of the Threadgill, Alfred Allen, heard of his arrest, he stepped forward as the first white person to publicly question his guilt. He, along with others at the Threadgill, started a defense fund and hired a lawyer for Martin.

It was a gesture that probably saved his life.

The case was prosecuted by Deputy County Attorney Edward R. Hastings. In a move that would be completely unthinkable in today’s justice system, Hastings allowed the victim’s 80-year-old retired father William Reagan to help try the case.

The older Reagan was hard of hearing but still mentally sharp and proclaimed to the press, “In the old time days, this man would never have stood trial, but I am an old man and an upholder of law and order. I intend to devote all my efforts to [Martin’s] conviction.”

The trial began on June 28; a jury composed of prominent Oklahoma City residents with well-known Oklahoma City surnames such as Hefner and Putnam would decide the case.

The prosecution

The prosecution’s case showed its weakness early on thanks to the expert cross-examination by Martin’s attorney, George S. Black. The star witness, Dr. Riley, who had on multiple occasions positively identified Martin as the man he saw with Reagan before the shooting, began to waver. When pressed on the issue, he replied that “all negroes look alike” but swore that the clothing worn by the suspect was the same.

The defense

Martin’s lawyer then demonstrated that, contrary to the testimonies of Officers Veasey and Rippey, Will Martin had never been arrested and had no criminal record.

Rippey’s credibility particularly took a hit when he testified that he heard Martin threaten Reagan from a “few feet away.” A transcript of his earlier statement showed that he had previously said he was about 60 feet away when the threat was allegedly made.

Martin himself took the stand and testified that he didn’t know Officer Reagan and had never seen him “until they drug me up to his dead body.”

His defense concluded with a string of white former co-workers and friends who testified about his high moral character and honesty. A reporter remarked that he’d never seen a case where “a negro had as many prominent whites testify as to his good character as Martin.”

The last person the jury would hear from before retiring for deliberations was the slain officer’s father. He made an impassioned plea to the men on the jury, begging them to deliver a guilty verdict. “There isn’t any question about [Martin] being the right man,” he said.

The verdict

With no eyewitnesses, no murder weapon and only the barest of circumstantial evidence, the men on the jury were asked to convict a man and send him to his death simply because he was black and wore winter attire near the murder of a white man.

After only an hour of deliberations, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty.

The ultimate fate of Will Martin has been lost to history. After he walked out of jail on July 1, 1910, he simply vanished from the record.

It is possible that he left Oklahoma City and began a life somewhere else; it is also possible that someone unsatisfied with the verdict might have inflicted his or her own retribution on him.

Interestingly, James Rippey, one of the officers who gave questionable testimony, later ran for sheriff of Oklahoma County and received an endorsement from the Ku Klux Klan.

He was not elected.

The case of officer Reagan’s murder still remains unsolved.

Print headline: Racial divide, A black man was accused of killing a cop in 1910 Oklahoma City, and the rest is history.