Michael Byrnes feels pure joy as opening day nears for the Oklahoma City Dodgers at Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark. Since the team’s season-ending final out on Sept. 17, its president and general manager has anticipated Thursday evening, when the Dodgers open its 2017 season against the Iowa Cubs.

“There is something unique and special to opening day,” Byrnes told Oklahoma Gazette. “People get excited. It’s partly the weather changing, but also baseball is on the horizon.”Opening day is perhaps the most anticipated game for fans, as it represents newness or a chance to forget last season.

As luck would have it, for Dodgers fans, this year’s opener is a chance to run on last year’s success: an American Northern Division title and Pacific Coast League playoff run.

Die-hard fan or not, the day signifies baseball is back in town. The game’s return electrifies many in OKC as evident when walking through the newly renovated Club Level on Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark’s second floor. Black-and-white images reveal the early years of the game in Oklahoma City, which began within weeks of the April 22, 1889, land run. (The land run also inspired the ’89ers name for the franchise from 1962 through 1997.)

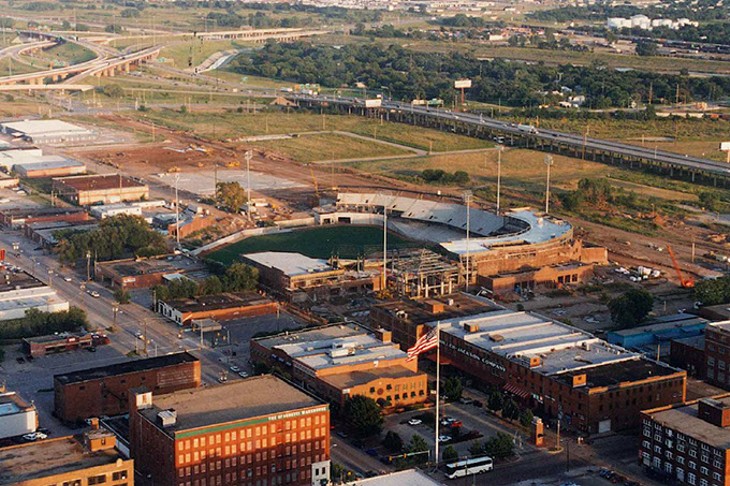

Other images of long lines outside Southwestern Bell Bricktown Ballpark and cheering crowds inside it dated April 16, 1998, are equally prominent and celebrate what is perhaps the greatest moment in Oklahoma City baseball and the city’s history. Built at a cost of $34 million, Bricktown Ballpark changed OKC in ways no one could have predicted when the first pitch was thrown 20 years ago on that sunny April day.

MAPS at bat

Before Bricktown became the crown jewel of downtown as a vibrant entertainment and dining district, it was a forgotten sprawl of desolate, sturdy brick warehouses. In the 1980s, the area began to catch the attention of developers as a neighborhood prime for urban development. Some capitalized as locals flocked to Spaghetti Warehouse, opened in 1989, and other eateries and nightclubs.Bricktown needed a spark, something to amplify early momentum. The flare came when city voters approved the Metropolitan Area Projects plan (MAPS), a one-cent sales tax initiative to jump-start the local economy.

Under MAPS, Mayor Ron Norick and the Oklahoma City Council pushed nine quality-of-life projects, including a downtown library, Chesapeake Arena and Oklahoma River and state fairgrounds improvements. In Bricktown, city leaders, with the backing of the business community, pitched building a San Antonio RiverWalk-style canal through the historic warehouse district and erecting a minor league ballpark with downtown views.

MAPS got off to a rocky start with sales tax collections lower than expected and projects consistently over-budget and behind schedule. Less than two years after voters approved MAPS, a truck-bomb exploded outside downtown’s Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building on April 19, 1995. The toll of the terror attack was immense — 168 people were murdered, hundreds more were injured and more than 300 downtown structures were damaged or destroyed in its wake.

Then, in 1997, one year before the ballpark opened, MAPS had a funding shortfall of $10.8 million. Six months before the venue’s scheduled grand opening, citizen comments revealed their concern about the future of MAPS.

Just shy of the third anniversary of the Oklahoma City bombing and nearly five years after voters approved MAPS, Southwestern Bell Bricktown Ballpark — the first completed MAPS project — was greeted by a sellout crowd of 14,066 fans.

Opening day

There are moments that define cities. Oklahoma City’s moments include the gunshot that sparked the Land Run of 1889, Oklahoma City Thunder’s 2008 inaugural Ford Center tipoff and the April 16, 1998, ceremonial first pitch thrown inside Bricktown Ballpark.Former Mayor Kirk Humphreys listed those moments during a 20th season celebration lunch the Dodgers hosted earlier this year. Humphreys, sworn into office days before the park opened, and Mayor Mick Cornett, who was a local sportscaster in the late ’90s, discussed the ballpark’s impact and its power to uplift the city.

Bricktown Ballpark generated excitement and became a tangible symbol of pride for a community reeling from the oil boom and bust of the 1980s, devastation of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing and anxiety about the city’s economic future.

“With the opening of the ballpark, we began to believe we could do it right in Oklahoma City,” Humphreys said. “The ballpark changed how we felt about our city and ourselves. It was a changing point.”As a MAPS project, it was created by and for the public, which contributed to the overwhelming sense of pride evident before the Oklahoma City RedHawks and the Edmonton Trappers took to the field that day.

“We just kept looking around because it had the feel of a major league stadium, a feel that we must be in some other city,” Cornett reminisced. “It was hard to imagine this was really ours. It really belonged to Oklahoma City and the sports fans of Oklahoma City. We’ve been running on positive energy since that day.”

![“Without [the ballpark], I think Bricktown wouldn’t be the way it is today without the growth, development and everything that’s here,” said Bricktown district manager Mallory O’Neill. (Oklahoma City Dodgers / provided)](https://media2.okgazette.com/okgazette/imager/u/blog/2976967/b09w1174.jpg?cb=1680879082)

Domino effect

Nearly 20 years after opening Bricktown Ballpark, the district surrounding it is a regional destination featuring countless restaurants, shops, hotels, a movie theater, a university, housing and more. Visitors stroll along the canal, ride the water taxi, visit the Oklahoma Land Run Monument and view American Banjo Museum’s massive collections.Nestled among the attractions, the ballpark, nicknamed “The Brick,” is viewed as the heart of the area, responsible for drawing people downtown and spurring an urban renaissance.

It’s hard to imagine what the district would be like without its ballpark, said Bricktown district manager Mallory O’Neill.

“Without it, I think Bricktown wouldn’t be the way it is today without the growth, development and everything that’s here,” she said.When city leaders first discussed a new ballpark, development trends were shifting to downtown areas as city planners emulated the success of projects like Baltimore’s Oriole Park at Camden Yards. Keeping professional baseball at the state fairgrounds was considered, but ultimately, the Bricktown site was chosen.

Bricktown Ballpark’s location has been key for building the game day experience in OKC, said Byrnes, who arrived here seven years ago. These days, the fan experience is as important as what happens on the field during a game.

“On a weekday night, someone can leave work, get home to pick up the family, grab a bite to eat in a local establishment and head in for the game,” Byrnes said. “On a weekend, they enjoy the Boathouse District, walk up the canal and into Bricktown for a game. Bricktown and baseball weaves together for a downtown experience. … We no doubt have passionate fans who come out and score every play, but we no doubt have folks that come out looking for something to do with their family.”

Beyond professional baseball, the park has hosted a slew of community events over the past two decades, from fundraising runs and walks for local nonprofits to snow tubing in winter months. O’Neill said the Dodgers are wonderful partners, from sending mascots Brix and Brooklyn to Brick-or-Treat Halloween to transforming the venue into a winter wonderland with special lighting and décor throughout December.

“We work so closely with the Dodgers in everything we do,” O’Neill said. “The Third Base Plaza is home to various walks and gatherings that happen in Oklahoma City. The ballpark is home to many important events — it’s a key part of the district.”

The venue remains a selling point for developers and business owners looking to invest in the city, O’Neill said. In recent years, the district has welcomed new office and residential developments. Bricktown is becoming the district where people can truly play, work and live.

Celebration time

This season, the Dodgers marks its 20th season in a variety of ways, including a commemorative brick opportunity, fans voting the All-Ballpark team, a giveaway night, merchandise and games honoring former players and those involved with the team back in 1998. During games, fans should watch the video board for images of the ballpark’s construction and opening day crowds as well as footage of key plays from the ’98 season.“We are so close to the MAPS story, operating one of the original facilities from MAPS,” Byrnes said. “It’s easy to forget how many people have moved here over the past 20 years and don’t appreciate that story. … We have an opportunity to reinforce that message and remind people what Bricktown looked like when the ballpark opened — there was no Lower Bricktown, there was no canal, there was no hotel beyond the outfield.”

But there was baseball; bats cracked, crowds roared and the smell of hot dogs filled the stadium, as did the laughter of children as they hugged team mascots.

Those sights, sounds and scents gave rise to today’s Oklahoma City.

“The line I use and nobody has ever contested it is, ‘No city in America has come as far as fast as Oklahoma City,’” Cornett said. “The ballpark was the beginning.”

![“Without [the ballpark], I think Bricktown wouldn’t be the way it is today without the growth, development and everything that’s here,” said Bricktown district manager Mallory O’Neill. (Oklahoma City Dodgers / provided)](https://media2.okgazette.com/okgazette/imager/u/blog/2976070/a02t97881.jpg?cb=1680879082)

Print Headline: Play ball; 20 years ago, Bricktown ballpark launched a hitting streak for urban redevelopment.