With its sky-scraping, multihued buttes and mesas jutting from the expanse of red soil, Monument Valley provided the backdrop for Hollywood’s vision of the American West. Photographer John R. Hamilton was on set for 77 films shot in Monument Valley’s five square miles of geological wonder on the Arizona-Utah border, beginning with John Ford’s iconic 1956 film The Searchers.

Through Hamilton’s lens, the bright reds and blue-grays of the towering rock formations feel impossibly vivid, nearly stealing the scenes from such stars as John Wayne, Robert Mitchum and Natalie Wood. Five decades worth of Hamilton’s revelatory photography is now on display in Hollywood and the American West at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, 1700 NE 63rd St., capturing both the humanity of filmic deities and the red rock cathedrals surrounding them.

Iconic location

“When we think of the West, we think of Monument Valley,” said receiving curator Kimberly Roblin, who set up the exhibit on loan from John Wayne Enterprises and the John R. Hamilton Collection. “And every time I look at these photos, I notice another detail.”Roblin was so thoroughly taken by the vistas captured in the exhibit she wrote a lengthy essay on the museum’s website calling for Monument Valley to be honored with an Oscar. So far, she has not found a bylaw that would keep the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences from honoring a geographical land mass. It is deserving given that so many films — not just Westerns, but time-honored classics like Easy Rider and even 2001: A Space Odyssey — would not be the same without Monument Valley.

Over the course of 68 photos, Hollywood and the American West chronicles not only the startlingly beautiful vistas of the area, but the hundreds of people who labored under extreme conditions to create The Searchers, Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo and El Dorado, Lawrence Kasdan’s Silverado and others. Hamilton’s ability to capture the dramatic and the delicate, the severity and the humor of Hollywood’s Westerns earned him the plaudit Remington With a Camera.

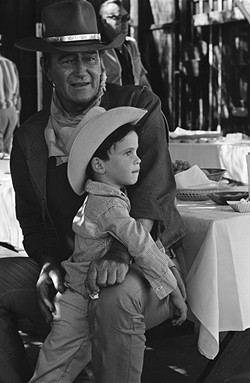

While the epic landscapes are certainly a character in Hollywood and the American West, the most memorable images in the collection are decidedly human. Wayne is shown playing on set with his youngest son Ethan Wayne, now manager of John Wayne Enterprises. Kirk Douglas stands outside his trailer, striking a pose in a cowboy hat and bikini underwear. Screen sirens Wood and Ann-Margret appear completely relaxed amid the dust and turmoil of an on-location Western.

“For me, I come from a history background, so I’m always drawn to the human element and the stories behind it,” Roblin said. “So that’s what I see as so intriguing about this work. You see John Wayne as a father, not just as Ethan Edwards [from The Searchers]. Or the great one of Kirk Douglas. It humanizes them.”

Surreal life

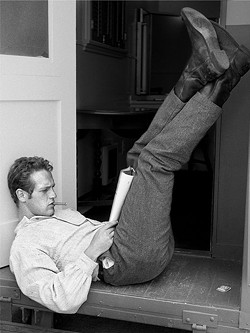

The signature photo of the exhibit shows 33-year-old Paul Newman reclining with his feet propped up inside a doorframe on the set of 1958’s The Left Handed Gun, reading an issue of The New Yorker. Roblin said this was an ideal choice as the defining image of Hollywood and the American West simply because it shows real life under unreal circumstances.“It’s visually so striking,” Roblin said. “It’s very minimal. Compared to the others, there isn’t a lot going on in the photo, but it draws you in. And I love that he’s reading The New Yorker. This was the same year that he shot Cat On a Hot Tin Roof and The Long, Hot Summer, so this was a big year for him, but you’d never know that because he’s just relaxing. I would love to know what article he’s reading.”

Other photographs illustrate the strange juxtapositions that take place when shooting period pieces. On the set of 1981’s The Legend of the Lone Ranger, Hamilton captures a tense technical scene in which a helicopter flies in close to shoot a stagecoach. The result is a stunning display of engineered anachronism and depicts the lengths to which filmmakers go to get the right shot.

Roblin said Hollywood and the American West is not only for Old West aficionados, because its depictions are strikingly universal.

“I’ve always loved movies, so I was inherently excited by this project,” she said. “But then to really see them, even as a moviegoer, it really gave me a glimpse into something I thought I knew quite a bit about — the making of movies — but I learned that I didn’t know about the sheer logistics behind making movies. And too, there is the human element. It’s a really an exciting exhibit for us. Even if someone thinks it’s something that isn’t up their alley, I would challenge them to think otherwise.”

That idea of challenging preconceptions of the West and the museum itself is a major part of what makes Hollywood and the American West so fascinating, she said.

“Some people think of our museum as doing just one particular thing, but we’re trying to change that perception and challenge people’s perception of the West and ask themselves, ‘What is the West?’ I would hope that people would set their preconceptions aside and even if they think they don’t have an interest in Western history or film, they should take a chance.”

Print headline: True West, Hollywood and the American West captures the drama and the humanity of classic films.