Public subsidized housing gave Laurinda Gaddis a chance.

“When I moved [to Oklahoma City], I just came up here with a trunk and a couple of suitcases,” Gaddis said. “I moved up from Mississippi with four children and was pregnant.”

Gaddis arrived in 1976 and was approved for a public housing apartment, where she lived until moving into a public housing single home in 1994.

“When I came up here, I was uneducated,” Gaddis said. “I had dropped out of school in the 10th grade. But when I had the apartment, I was able to go to night school.”

Money was still tight for Gaddis and her children, but living in an affordable public housing unit allowed her to continue her education instead of having to work a second or third job just to make ends meet.

The project and “the projects”

Gaddis is one of nearly 5,900 OKC residents currently living in a public housing unit, which can include family or senior apartments or 640 single homes scattered throughout the city.

Add in those who receive housing choice vouchers, also known as Section 8, and the Oklahoma City Housing Authority serves nearly 16,000 people who might otherwise have no other housing option.

Public housing, sometimes called “the projects,” has not always gained a positive reputation in American society. Popular culture can paint these developments as dens of crime and poverty that should be avoided. However, that negative image doesn’t fit with the original vision for a national system of subsidized housing.

“The federal public housing program has the reputation as being a decaying dumping ground for housing some of the poorest families in the U.S.,” writes JA Stoloff in a report for the Department of Housing and Urban Development. “But it was rooted in a very idealistic and paternalistic view of helping the working class, not necessarily the worst off segments of society.”

The Housing Act was passed by the U.S. Congress in 1937 in an effort to serve the needs of the “submerged middle class” who were struggling during the Depression, Stoloff writes. The plan was to funnel federal dollars to locally controlled housing authorities that could best address the housing needs of those who were on the verge of homelessness.

With a national depression driving poor families to the cities, housing authorities took in people of all backgrounds. Fast forward past generations of suburban flight, and many housing units were left serving a mostly minority population.

A needed service

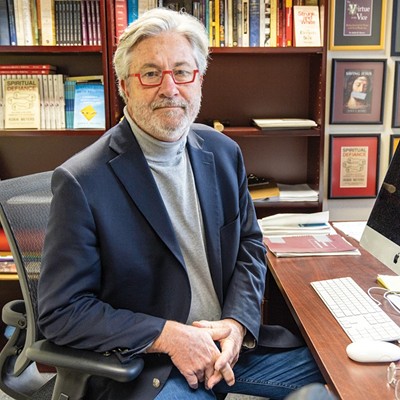

The OKC Housing Authority was established in the mid ’60s with a mayoral-appointed five-person board that hires the executive director. Mark Gillett serves as executive director in OKC and oversees the department’s 15 developments and Section 8 voucher program.

“They are not made the same, they are not governed the same,” Gillett said about the nation’s hundreds of public housing authorities. “We all have different characteristics.”

One of the characteristics of OKC’s public housing developments is they are integrated into the city rather than built as massive compounds more commonly seen in cities like St. Louis and Baltimore.

“We like to think that you can’t tell [what is public housing] when you drive by,” Gillett said.

Since its early days, thousands of Oklahoma City residents have been in need of public housing, and occupancy was at 94 percent several years ago. However, following the economic downturn in 2009, the agency’s occupancy rate hit 99 percent.

Last year was a difficult year for the housing authority, as funding from the federal government was drastically reduced through the sequester, marking the first time the government failed to fully fund the Section 8 program since its inception in 1972.

“Last year was a bad year in Section 8,” Gillett said. “We all stopped issuing vouchers because there wasn’t enough money.”

Many housing authorities across the country had to take vouchers back.

“We did not,” Gillett added. “But we got close.”

Realizing the devastation of their decision, funding was reinstated this year by Congress, Gillett said, which allowed the housing authority to reopen Section 8 vouchers to all in need. Last month, over 800 individuals applied for vouchers as the program was brought back to full life.

Public housing offered Gaddis a chance to raise her family, and now, at age 61 and unable to work multiple jobs to make ends meet, public housing continues to offer her a quality lifestyle.

“I’ve got a few health issues where I don’t see myself getting any more employed than I am now,” said Gaddis, who currently delivers meals for Sodexo. “The [housing authority] has given me a lot.”