Violence erupted at a local teen club on the night a young Ronnie Johnson decided to stay home. As a teenager growing up in northeast Oklahoma City, violence was part of everyday life for Johnson.

The urban area’s high rate of crime and violence contrasted Johnson’s daily activities, such as high school sporting events, socializing with friends and simply taking after-school walks.

“It was always the same thing,” Johnson described. “When you went out, you knew someone was going to fight, someone was going to shoot.”

One day, violence and adolescent angst culminated after a Northeast High School basketball game. It was typical for students, some from neighboring high schools, to go socialize at a club after games. After a difficult loss, Johnson didn’t join his teammates or the others. The next morning, Johnson learned a friend was killed during a dispute involving a girl.

“It really dawned on me,” Johnson said, “that people were losing their lives over something that shouldn’t happen. … I lost friends to nonsense.”

Surviving the teenage years doesn’t guarantee a clear path to escaping violence, explained Johnson, who continued to lose friends from Oklahoma City’s northeast side to gun and knife violence.

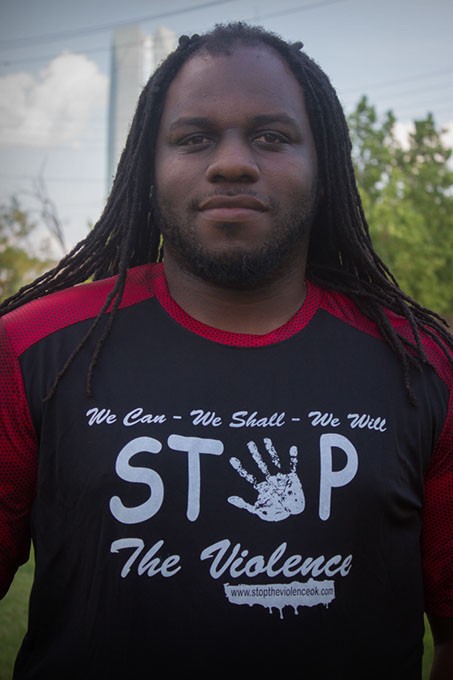

As hip-hop artist Grand National, Johnson recorded “Black Star” in May, which detailed his personal experience with violence and the murder of his 23-year-old friend. Jalen Ware was killed last year during an armed robbery in northeast OKC.

This violence, and the trauma that follows, is a terrifying reality in some urban communities. Homicide is the leading cause of death among African-American youths and the second leading cause of death for all young people ages 15-24, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

What is violence?

Violence is not limited to a terrorist attack, shooting or bloody uprising. In fact, violence is defined by the World Health Organization as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person or against a group or community, which either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation.”

According to the CDC, the Sooner state holds a slightly higher homicide mortality rate than the national average. Oklahoma’s firearm mortality rate is 15.6 per 100,000 people, compared to the national rate at 10.2 per 100,000 people.

In a recent study, Oklahoma was named one of the most dangerous states in the nation. It ranked No. 50 on a survey reviewing home and community safety, road safety, workplace safety, financial safety and safety from natural disasters, according to personal finance website WalletHub.

Violence is preventable. In a state impacted by violence, who is part of the growing movement to end the persistent brutality?

Message to youth

On Mother’s Day 2010, 21-year-old Kruz Laviolette was shot in the back after breaking up a fight in northeast Oklahoma City. The 21-year-old man died in front of his family, including his younger brother and sister.

Troubled by his cousin’s murder, Kuinten Rucker decided to be a force for change.

“I didn’t want to go out and hold up a sign that read, ‘Stop the Violence,’” Rucker said. “I wanted a way to really engage the youth. Get their attention and say, ‘Hey, there are other options.’”

Months after the tragic loss of Laviolette, Rucker created Stop the Violence, an organization dedicated to working to reduce violence in schools and neighborhoods. Each year, Stop the Violence hosts youth camps that teach singing and dancing. The songs match the popular beats of hip-hop songs, but the lyrics preach a positive message.

Children ages 4-18 participate in the Stop the Violence camps, which preventatively educate youth on topics such as gangs, bullying, sexual abuse, drugs and suicide.

“We hear a host of different success stories,” Rucker said. “Some parents tell us their children were having issues at school with bullying before coming to camp.”

The camp’s message resonates with the children past the final day, Rucker explained. One camper shared with Rucker about a time when he was asked if he wanted to use drugs. The camper replied no and within seconds, a police car drove by. The situation could have ended very differently for the camper.

“He heard my voice in his head,” Rucker said. “Stories like that is what we want to hear. Our program is working.”

Rucker believes Stop the Violence’s success comes from its ability to morph arts with a needed message.

The next camp runs 6-9 p.m. July 18-23 at Douglass High School, 900 N. Martin Luther King Ave.

“This program is open to everyone,” Rucker said. “It’s not just for at-risk youth or kids from certain neighborhoods. Violence happens everywhere. It doesn’t matter what neighborhood or school you come from. We try to prepare the youth to get them ready for anything.”

Challenging violence

Following a community meeting discussing the rate of violence and support systems established for victims, Sara Bana and Dwain Pellebon created Ending Violence Everywhere (E.V.E.), a nonpartisan citizens’ coalition demanding change in the culture of violence by promoting education, prevention, treatment, intervention and love.

“Violence is not a natural mode for people,” Bana explained. “We can love. To have love and compassion in your life makes you a more whole and complete person. It also makes the world a more beautiful place. We have to respect one another.”

Less than a year after the nonprofit’s inception, a white police officer shot unarmed Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. The incident touched off more violence, protests and national debate. People feared Ferguson could happen anywhere. Pellebon and Bana saw an opportunity for E.V.E. to play an important role in strengthening the police relations of the community.

“We didn’t want something to happen in Oklahoma City or central Oklahoma that was happening nationally,” Pellebon said. “That mobilized us.”

Community leaders and law enforcement representatives participated in a public forum on police and community relations hosted by E.V.E. in March 2015. The nearly five-hour gathering allowed the public to ask questions and share personal stories. Law enforcement, which included representatives from Oklahoma City, Norman, Midwest City and two sheriffs’ departments, listened to the concerns and tried to address them.

The forum gave rise to the Police and Community Trust (P.A.C.T.) Initiative and Summit, which included involvement by local police chiefs, sheriffs and community leaders. In late January, the initiative approved 20 action items for the community, including stronger law enforcement presence and engagement at community events, educational brochures on interacting with police and implementing anti-bias training.

Now, Bana and Pellebon co-chair the initiative and are tasked with studying the success of the action items. Additionally, E.V.E. produces a local radio show that explores the causes and contributing factors of violence.

“We’ve focused on passive violence issues, like poverty, because we feel those issues are the conditions that lead or cause violence,” Bana said. “If we can act in that situation, then we may be able to prevent future incidents of violence.”

Public involvement

Those fighting to prevent violence in OKC recognize that it takes everyone involved to reduce violence.

To tackle violence, there must be positive youth programs available for children, Rucker explained.

Public schools cutting or reducing fine arts programs are a danger for the community. Speaking from his own experience, Rucker contends that music programs, marching band and dance classes offered him a positive and creative outlet, leaving little time for juvenile crime.

Johnson believes that everyone — parents, teachers, family members, coaches, etc. — has an important role in stopping violence before it starts.

“Where it starts is telling the kids they can achieve greater than what they see,” Johnson said.

“Don’t let something stop you. Dream as big as you want,” Johnson said. “Once you understand about what is really out there, you are not going to have time to be violent.”

Johnson argues contemporary capitalism breeds a destructive society with rampant with unhappiness, the breakdown of the family, poverty and violence.

Both Bana and Pellebon see poverty, as well as mental health, education and politics as underlying causes of violence.

While some might conceive the issue of violence as too big to tackle, individuals like Johnson and groups like Stop the Violence and E.V.E. know how to enact solutions. By mobilizing youth, concerned community members and listeners, they help shape public and government agendas and create an important force for reducing violence in the OKC area.

Editor’s note: Gazette intern Ian Jayne contributed to this news report.

Print Headline: OKC’s struggles, A solution lies in truly understanding violence and educating youth.