Brandon McDonald is motivated. The teenager who has his future mapped out with the hope of attending a welding trade school knows that he’s no longer the kid who grew up on the streets.

“There are only two cards you are ever dealt,” said McDonald, whose cards are tied to his gender and his skin color.

The other cards, like education, career, friends and hobbies, are controlled by himself.

“At the end of the day, its what you did during that dash mark between when you were born and when you died,” McDonald said.

He is currently in the care of the state’s Office of Juvenile Affairs and is dealing himself a whole new set of cards. His confidence is tied to Man UP, a youth outreach retreat of the FACT (Family Awareness and Community Teamwork) program at the Oklahoma City Police Department (OCPD). In this novel and ambitious initiative, Lt. Wayland Cubit and Sgt. Tony Escobar take about 20 inner-city male teenagers on a weekend of self-discovery, personal growth, manhood and mentorship. Police officers lead the activities and the discussions, which center on themes of integrity, compassion, confidence, self-control, perseverance, bravery, humility, authority and responsibility. Male mentors’ own experiences and perspectives provide a multidimensional understanding of the teens they will mentor during the 24-hour period and into the future.

“To know that somebody from the same background can turn around [their life], … it has given me more hope that I can do it,” said McDonald of his mentor, a local college student. “I have motivation. I can relate to that.”

Lessons in labels

OCPD is by no means the first or only law enforcement agency to successfully run a youth mentor program. However, the fact that the program continues to evolve more than a decade after its start is a testament to the officers’ diligence to make a difference in the lives of at-risk youth.FACT began in 2007 as a gang prevention program under the premise that at-risk youth and achievement can go hand in hand when officers help facilitate that connection by introducing youth to positive societal and cultural values, holding high expectations for behavior and modeling those behaviors.

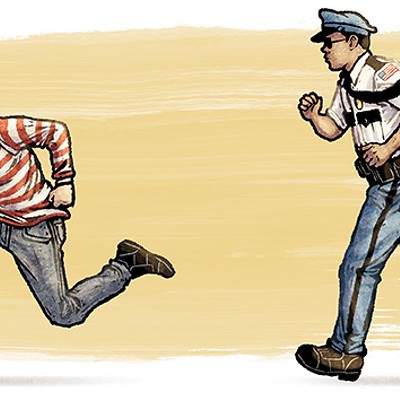

Much of that is built into Man UP. OCPD hosted its seventh retreat the weekend of March 17, when 21 pre-selected young men, including two from the state’s Office of Juvenile Affairs, arrived. Officers handed out backpacks to the teenagers. Inside those backpacks were sand-filled bottles with white labels on which officers wrote characteristics like angry, lazy, selfish, mixed-breed and liar, among others.

The participants were told to wear the backpacks at all times.

“Society will sometimes label you without even knowing you,” said Escobar, an 11-year veteran of the police department who stepped into the role of Man UP organizer this spring. “[The participants] had to carry these labels for 24 hours. At first, it was awesome. They had full energy. By the end of 24 hours, it had to have hurt. … That’s when we told them even though society may label you, you don’t have to carry it. You can change your outcome.”

Warren Pete, the Man UP curriculum coordinator, shared that participants, officers and mentors spent significant time discussing the labels.

“What are some of the things you’ve been labeled?” he recalled asking. “What are some of the things that people have called you? You haven’t been called this? Well, someone may call you this, and you have to be prepared to handle it.”

When mentors noticed that the weight of the backpacks was taking its toll on the teenagers, they’d offer to wear it for a short period of time. There was a lesson in passing along the backpack.

“Your manhood is not defined by how much you can carry alone but in admitting that you are going to have problems with the weight you are carrying and you will need a spotter from time to time,” Cubit said. “You’ve got guys who are willing to spot for you.”

New perspectives

Along with building positive relationships, Man UP seeks to increase understanding between youth and police. Both McDonald and Quavyon Durham, another Office of Juvenile Affairs youth, explained how their perspectives changed about police.“You have this mentality if you’re young and you grew up in the streets [about police],” McDonald said. “They are doing their jobs. They are called to serve.”

One of the officers who spoke to the teens explained that “he didn’t like the police but grew up to be one,” said Durham.

Powerful messages came from the mentors and officers’ personal stories from their childhood and teenage years. Like the participants, the mentors and officers made mistakes, but unlike some of the teenagers in the room, they weren’t caught, Pete said.

“We understand that people had to open up doors for us and help us,” Pete said. “We want them to know that they have the same support system. They have another chapter to write.”

Four weeks had passed since McDonald and Durham graduated from the Man UP program; however, the two said the lessons are still with them as they work to complete their programs at Tecumseh’s Central Oklahoma Juvenile Center, the state’s most secure juvenile detention facility. A handful of credits away from earning their high school diplomas through the center’s charter school, both see themselves seeking higher education when they return to their communities. For McDonald, that’s trade school, and for Durham, it’s a business degree from Rose State College followed by culinary school.

As for their mentors, both said they are already becoming a big part of their lives through continued conversations on the phone.

Durham sees his mentor as a big brother who’s teaching him the skills to be a man.

“I am the big brother in the house; I’m the oldest,” said Durham, who has a younger brother and sister. “When I was getting into trouble, I didn’t know how to be a big brother. I grew up with just my mom, and she couldn’t teach me everything that my father would have. He passed when I was younger. I never got to meet him. It was hard. I was going about trying to be a man on my own, but I didn’t know I was doing the wrong things to get there. I was on the wrong path.”