Western art is a broad church encompassing many centuries, myriad geographies and a multiplicity of styles and approaches. Art of the American West, however, might often be pigeonholed as depicting regional landscapes and personages through a generally realist lens. Do You See What I See? Painted Conversations by Theodore Waddell, which runs through May 13 at National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, 1700 NE 63rd St., nuances perceptions of American Western art, intersects with other artistic movements and questions the relationship between art and representations of reality.

Theodore Waddell was born in Montana in 1941, five years before abstract expressionism came onto the scene in New York, but the artistic movement would eventually influence his own sensibility.

“He comes at it from place more than anything,” said Melissa Owens, interim chief curatorial officer and registrar and collections manager at the museum. “He had his studio education in the ’60s, in a time when modern art was going in various directions. He brought that new mentality back to what he knew.”

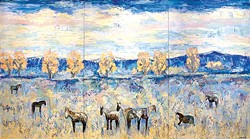

With a rancher for a father, Waddell spent plenty of time around cattle and horses; these animals manifest as subjects in his art, but not in conventional ways. Waddell’s technique — using loose, expressionistic brush strokes to render his subjects and landscapes — couples a distinctly Western approach to art with a more avant-garde mode to create a hybridized blend, Owens said. Pieces created over a decade apart, such as “Lynn’s Narcissus,” dated 1997, and “Argenta Horses,” from 2009, demonstrate Waddell’s evolving artistic approach in relation to similar subjects and artistic abstraction.

“Throughout his career, like any good artist, his style changes,” Owens said. “There are periods in his career in which things become much more abstract, but they’re still very identifiable.”

The exhibit’s 43 pieces consist primarily of oil paintings and encaustics (wax-based media that lends a transparent appearance), but the collection also showcases Waddell’s printmaking skills. Monotypes (singular type prints), etchings and lithographs also feature in the exhibit.

In addition to animal subjects, Waddell also depicts landscapes and cloudscapes, which Owens defined as a “quick interpretation of cloud formations on a dark horizon.” Included works also play with scope and scale; a towering triptych depicts a mountain range and foregrounds the landscape.

For Owens, Waddell’s work fits into the tradition of American Western art in a more expansive way.

“He’s very much a Western artist; it’s just not what a lot of people would think of as Western art, like a [C.M.] Russell or a [Frederic] Remington,” Owens said.

Changing perceptions

Waddell’s exhibited work straddles the intersection between abstraction and depictions of the American West, marking a departure from many of the museum’s more realistic pieces. Viewers will find context materials, such as quotes from the artist, to help orient their perspectives.“If you’re not very well-versed in contemporary art or non-realistic art, it takes a little bit to adjust your sensibilities,” Owens said, “but if you spend some time with it, and especially if you’re reading the titles… you naturally get what he’s doing.”

While viewers might find Waddell’s work hard to interpret up close, Owens said that stepping back and approaching the art from a greater distance can help bring things into focus.

Owens said the curatorial process prioritized visual arrangement, with subject matter and color as organizing principles.

The exhibit arose partially from recently retired chief curatorial officer Michael Leslie, whose previous work at the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis, Indiana, connected him with Waddell, Owens said.

“Mike’s idea, really, was to bring Theodore’s work here and share it with our public as a means to broaden our scope,” Owens said.

Even the exhibition’s title, posed playfully as a question, invites discussion about viewers’ perceptions in relation to the art and the artist.

“It’s Ted’s vision,” Owens said. “You can also see what he saw at the time and what he’s trying to evoke: the feelings of a place and time.”

In order to help inspire such “painted conversations,” Owens said the museum will offer specific programming related to the exhibit. On March 13, with museum admission (free to members), patrons can participate in a gallery tour led by the artist himself 10:30 a.m.-11:15 a.m.

Noon-1 p.m. March 14, the museum will continue to host the latest iteration of its Brown Bag Lunch Series, My West, in the S.B. “Burk” Burnett Board Room. With no reservations required, patrons can bring their lunches brown bag-style or purchase them from the Museum Grill. During the lunch, Waddell will speak about the factors of his life that shaped his artistic output.

In addition to his career as a painter, Waddell has also written children’s books. Story Time with Tucker the Bernese Mountain Dog will take place 2 p.m. March 19. Museum members or patrons who purchase museum admission can interact with a dog from Human Animal Link of Oklahoma during story time.

By asking questions about Western art and abstraction, Do You See What I See? eschews the idea that American Western art only consists of photorealistic paintings of cowboys or horses. Rather, the exhibit and its related events aim to engage in a conversation about perception and the ways in which an artist such as Waddell attempts to reimagine it.

Museum admission is free-$12.50. Visit nationalcowboymuseum.org.

Print headline: Western abstractions; Theodore Waddell’s work poses questions of realism and expressionism.