Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs as they are known in the health community, are gaining a lot of attention these days, according to nonprofit researcher Adrienne Elder.

ACEs, resilience and holistic healing are trending topics in elementary schools, police departments and hospital rooms nationwide because the latest scientific evidence suggests that ACEs like abuse and neglect are not only common but are the culprit for societal ills that range from premature death, diabetes, heart disease and cancer to domestic violence, anxiety, depression and poverty.

“Our culture is in the midst of a mind shift,” Elder said. “We’re going from ‘Let’s solve these problems that appear isolated and random’ to ‘Let’s address the cause of these problems long before these problems even arise.’”

The movement to prevent ACEs begins with parents, Elder said.

“We all know the story — like father like son, like mother like daughter — we know this to be true, yet we hardly talk about the evidence behind that truth,” Elder said.

Resilience: The Biology of Stress & the Science of Hope is a 2015 documentary that sheds light on ACEs and their prevention. The documentary has been shown in town hall meetings across the country and will be screened in Oklahoma City at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 8 at The Salvation Army of Central Oklahoma Area Command, 1001 N. Pennsylvania Ave.

The film reveals daunting statistics: 28 percent of children nationwide experience physical abuse, 27 percent experience substance abuse and 20 percent experience sexual abuse. A child with two or more ACEs is twice as likely to develop heart disease, three times as likely to suffer from depression and has an expected lifespan that is 20 years less than average.

According to United Health Foundation, 32 percent of Oklahoma’s children experience two or more Adverse Childhood Experiences.

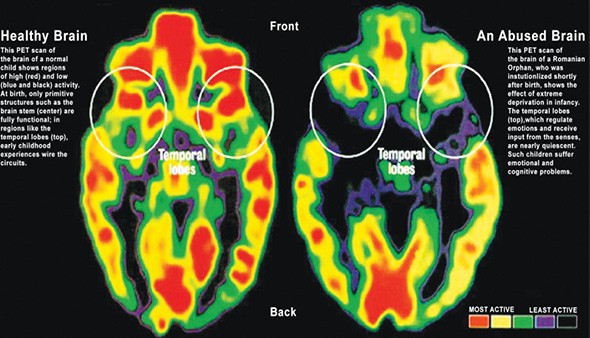

A 2016 report from the American Academy of Pediatrics said that “new research has shown that neural connections, which are particularly vulnerable in the early stages of life, even infancy, can be disrupted and damaged during periods of extreme and repetitive stress, toxic stress, like that which is experienced during ACEs.”

“We think, ‘Kids are young; they don’t know what’s going on and they won’t remember anyways,’” said Dr. Jack Shonkoff in Resilience. “Well, the child may not remember, but the body remembers.”

Forty-four-year-old Tammy Parent doesn’t need a reminder of the trauma she endured as a child. Parent prevented her mind from going down memory lane, she said, with a methamphetamine addiction that lasted decades.

“When my mom got sick, everything went downhill,” she said. “She became addicted to pills, and even though we were poor before that, it got a lot worse after.”

Parent said her mother’s opioid addiction led to her parents’ divorce, being molested by one of her mother’s boyfriends, doing poorly in school and eventually repeating the pattern of poverty and addiction that seemed as inherited as anyone’s tangible family heirloom.

Despite efforts Parent made to better herself, including earning a nursing degree, she eventually fell back to what she knew.

“At one point, we were doing better than OK,” Parent said, referring to she and her husband, who is fighting addiction while in prison. “We were making over a hundred thousand a year.”

Today, Parent lives in a rundown apartment in Muskogee. When rent money isn’t available, she lives in her car.

Poverty expert Ruby Payne said poverty is a common result of ACEs.

“Poverty is not black-and-white; it’s a language we learn from childhood that’s spoken in the mind and heart,” Payne said.

Getting Ahead

In 2000, Payne joined addiction counselor Philip DeVol and author Terie Dreussi-Smith to launch Bridges Out of Poverty, a nationwide program aimed at addressing individuals ACEs and moving them out of poverty.

In Oklahoma, Bridges is offered by Department of Human Services and Oklahoma Department of Corrections along with several faith-based organizations.

Bridges offers Getting Ahead classes that teach participants the “hidden rules” of each economic class and how to move from poverty to the middle class and from the middle class to wealth.

Elder speaks to organizational leaders and trains staff to become Getting Ahead instructors.

Participants receive free dinner and childcare with each class they attend as well as a monthly stipend.

“They have made all the difference to me,” said Parent, who attends Getting Ahead classes in Muskogee.

Parent said she will graduate from the Bridges program on Dec. 11. That same month, she said, she will reach her one-year sobriety marker.

Having incurred several felonies related to her drug use, Parent said the Getting Ahead classes have offered a chance for redemption.

“They are like my family,” she said. “It’s hard to talk about my past with people who don’t understand, but everybody in the class totally gets it.”

She said that while her own daughter has unfortunately experienced her fair share of ACEs, she hopes her turnaround will break the family’s history of generational poverty.

To see Resilience in Oklahoma City, visit eventbrite.com.