For five years, Chaya Fletcher worked her fingers to the bone at Urban Roots to keep the true legacy of Oklahoma City’s Deep Deuce neighborhood alive.

Saturday night, however, the restaurant, bar, art gallery, music hub and poetry venue that she and her husband ran closed its doors at the end of a weeklong celebration of culture and artistic collaboration.

Dozens of artists, musicians and venue fans participated in Preserving Our Roots Music Fest, a lineup emblematic of the rich motif Fletcher painted at Urban Roots for half a decade. For many, the weekend announcement was a disheartening surprise.

“I just want the world to know how hard we tried to provide a culturally artistic outlet in such a worthy place,” Fletcher said after the final celebration. “We feel like we did good work, and we hope, because of our efforts, culturally significant ventures continue to happen and we show up to support them.”

The venue began with a simple goal.

“There weren’t many spaces that I felt were open to the arts,” Fletcher said just weeks ago before making tough decision to close Urban Roots for financial reasons. “You can go and have a nightclub and dance and party, but when you have a black artist or poet or screenwriter or dancer, where do they go [to showcase their art]?”

For at least half of the 20th century, Deep Deuce was the answer to that question in Oklahoma City, an answer that became known nationally by word of mouth. The loss hit the community hard.

“When we opened our doors in 2010, we hoped to honor and preserve the roots of our ancestors in a sacred place,” Fletcher wrote in a post on the venue’s official Facebook page. “We feel we were instrumental in initiating new opportunities for culturally significant ventures and hope for those to see continued success.”

Cultural exchange

While Deep Deuce is now recognizable for its condominiums and walkable streets that attract affluent OKC newcomers, its legacy is that of a lively and artistic community borne from segregated America.

“I think it’s been invaluable, Urban Roots being there,” said Anita Arnold, executive director of Black Liberated Arts Center (BLAC) on N. Lincoln Boulevard. “I see them as a … representative of the history down on Second Street. It is important that there is a presence of a rich and wonderful history, and they represent that. If they [go] away, I don’t think we would have anything to remind us of that history.”

Arnold’s comments also came before the announcement of Urban Roots’ closure, and it remains to be seen what will happen to the historic building that housed the establishment at 322 NE Second St. But the outpouring of love, respect and positive memories posted to the venue’s Facebook page shows that Fletcher’s efforts will not soon be forgotten.

“I met and made friends in there that I will cherish for a lifetime,” one woman commented.

“This was our oasis. I’m broken-hearted,” added a young man with videos of Urban Roots poetry and jazz performances on his Facebook page.

Fletcher helped launch the business in 2010, developing a “flexible and creative” concept intended to promote culture and interaction.

“When you drink and break bread together, you use the food to bring people with differences together in a shared, collected space,” she said. “On some levels, it has been very well-received. On other levels, it has been kind of confusing to some people who don’t really get the absence of this cultural element in Oklahoma City.”

That cultural element is significantly more absent this week, for both Deep Deuce’s legacy and any Oklahoman invested in the arts.

“[It was] a very fragile relationship to get people to understand that, yes, we’re black-owned, but this isn’t segregation again,” Fletcher said. “This [wasn’t] a black-only place.”

A mother of three, Fletcher heard those misconceptions, and she* spoke of the business’ “dollars” not being as “diverse” as they needed to be. When Urban Roots was featured on the reality TV show Restaurant: Impossible, a few people called her to chastise her.

“I have had people call and threaten us. They’ve called me a racist and a nigger in the same sentence because they didn’t see any white people working here when we were on Restaurant: Impossible,” she said. “People have yelled at us for not having any white people [pictured] in the art on our walls.”

The incongruity of those criticisms aside, Fletcher points out that the positive comments she has received greatly outnumber the obnoxious ones.

“For me it’s like, ‘What’s the big deal if you’re the only white person here?’ I’m usually the only black person in a lot of places I go,” she said. “In situations where you’re the only white person, you’re not really conditioned to do it. It’s different when you’re part of the majority, and then you go to this place where you’re not anymore. It’s just a level of comfort.”

African-American America

As Urban Roots reaches the end of its run, few hints remain of Deep Deuce’s past prowess and its importance to the community.

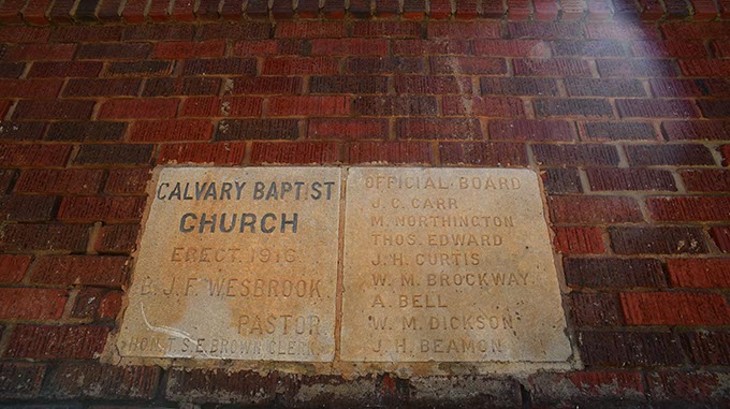

Arnold praised Dan M. Davis Law Offices at 300 N. Walnut Ave. for restoring the old Calvary Baptist Church building and making it available to the community it served for so many years.

The church, however, could be seen to represent a great and competing irony of the district. Much of city’s urban growth has been young, wealthy and white, with talented college graduates actively recruited to the city on a promise of culture, opportunity and bustling development.

But that demographic does not remember or consider the world prior to Interstate 235 and the phrase “urban renewal.” It likely knows Dan Davis’ television commercials better than it knows the history of the church or how it once turned down the application of a pastor named Martin Luther King Jr. because he was too young. And while the venue’s reputation as a classy, hip establishment grew, the knowledge of Halley Richardson’s shoeshine parlor, the Oklahoma City Blue Devils and passionate jazz-band battles slips away.

“When you go to Deep Deuce, you don’t expect to see a place like Urban Roots, even though you should because of the history,” Fletcher said this spring.

The area’s history is something Fletcher and Arnold both fear is absent in the general public, and Urban Roots’ closure frightens historians even more.

“History gets lost so easily,” said Arnold, whose organization sponsors the annual Charlie Christian International Music Festival, which started in Deep Deuce and now reaches across Oklahoma. “I would hope that the generation there now and going forward could, in fact, know the history. I would think that history should come forward with future generations moving in there.”

That might be a long, uphill battle for Arnold, Fletcher and others concerned with the intellectual preservation of both troubling and inspiring times in Oklahoma. It raises an old question that can be answered with an equally old joke: How does one discuss the effects of “separate but equal” while celebrating the rich history of African-American America?

Very carefully.

“This is my favorite place to play in OKC. It’s definitely deserving of [its] good reputation,” said Jeremy Thomas, a versatile musician who played at the venue during its final week. “It really means a lot because it [kept] the live music scene here fresh. When it comes to live music — predominantly along the lines of jazz — it’s not just an African-American heritage; it’s an American heritage. And this place [helped] us keep that alive.”

Inclusive history

Other artists raved about Urban Roots in person and posted regretful messages about the closing across social media.

“When you come to hear a jazz group here, you’re going to hear them do their thing,” said trombonist Zac Lee, “whereas, most places, you’re playing cocktail music, you’re playing dinner music. That’s fine and all. I spent most of my life learning thousands of these old songs, and I do want to play them from time to time. But here I get to play new stuff. You get to throw down and do your thing.”

Lee and Thomas’ comments were made before Urban Roots closed, but both said they felt pride taking the stage in such a historic area of Deep Deuce.

“When you look at Charlie Christian, you know, that name is slowly disappearing from our lexicon,” Lee said. “He was a major figure, not just in the development of jazz but in the development of American music. We’re all very aware of his presence still being here. We come here with an awareness and a respect for this history.”

Fletcher’s family lived much of that history, including during the time the building that housed Urban Roots was home to Ruby’s Dance Hall and Grill, a restaurant where Fletcher’s grandmother waited tables while pregnant with Fletcher’s mother.

“I think some of my proudest moments are when people of my grandparents’ age are here in Urban Roots and I see the sense of pride they have,” Fletcher said this spring. “Whether they know me or my family, when they come in and see that all that remains of their childhood is one black-owned business, I get to hear the stories they have. They have taught me so much — things I would never have known because I’m 35 and I grew up in an integrated society.”

What’s next?

Where will people go now to reminisce on how Deep Deuce used to be? What will the next generation of Oklahomans remember or understand about Deep Deuce’s significance? Fletcher worked for half a decade to make her venue an important part of those answers, and soon, those questions will need even more focus.

“How do we create a medium?” Fletcher said of the thought behind her business. “I think that in OKC specifically, yes, we have advanced in race relations, but we still have race issues.”

Fletcher pointed to the preoccupation that some people have with Bobo’s Chicken, a legendary late-night food establishment at 1812 NE 23rd St.

“They say, ‘Oh, I’m an urban pioneer. I took my kid to Bobo’s. We waited in line in the ’hood,’” Fletcher said. “People think that black is the ’hood or sketchy or whatever. We can be OK with who we are as a culture but still be appealing to all people.”

With Urban Roots, Fletcher attempted to fill a community and cultural void.

“We are more than what people just stereotype us as. We are educated. We like the same things you like. We like good music, good food, good wine. We are the same in so many ways,” she said.

Her venue existed as a statement to that fact, a reminder of important history and a colorful horizon for the future.

“Classy?” Fletcher considered the term when told that’s how Urban Roots had been described. “I don’t think it was intentional. I think it’s a result of who we attracted. We attracted people who were outgoing, traveled, educated, fashion-forward people. Are we black hipsters? I don’t know if there’s a name for us yet. But maybe that’s who we are because we are people who are driven by local fashion, music, art and poetry. We are the people who made Deep Deuce cool originally.”

Print headline: Withering roots, One of the few remaining black-owned music, art and food venues in the historic Deep Deuce district announced its closure.

*Note: This story was updated online to correct a grammatical error.