Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of weekly stories focusing on issues surrounding the possible legalization of medical marijuana in Oklahoma.

In the 22 years since California passed Proposition 215, which legalized cultivation, possession and use of marijuana for medical purposes, 28 other states followed suit, reversing years of demonization of cannabis and restriction on institutional marijuana research.

On June 26, Oklahoma voters could choose to become the 30th state to approve such a measure.

The vote on State Question 788 comes after past efforts to bring medical marijuana to a state question failed. In 2014, a group called Oklahomans for Health circulated petitions for a statewide vote but came up short of the required signatures. In 2015, a separate group called Green the Vote failed to gather the 123,000 signaturess necessary to add the issue to the ballot. The following spring, Oklahomans for Health again tried, this time as a statutory change. On that try, the group was successful in collecting signatures, but the vote became the subject of a lawsuit alleging then-Attorney General Scott Pruitt changed the wording of the ballot to sound as if the state question was calling for full legalization, including recreational use.

Oklahoma Supreme Court ruled for restoration of the original language, calling for a 2018 vote, which prompted Gov. Mary Fallin to schedule the vote on medical marijuana for June 26, in conjunction with the state’s primary elections.

Now, the push is on to understand what medical marijuana legalization means for Oklahomans.

Herbal remedy

The needs of patients — from children suffering from seizures to adults experiencing chronic pain — united groups who weighed in on draft petition language at public forums more than two years ago. Through feedback from medical marijuana advocates, including current patients and their families, and with legal and medical guidance, the end result was SQ788, the Medical Marijuana Legalization Initiative.

“It was written through a public legislature of advocates,” said Grove, a Tulsa resident who remains active in the Vote Yes on 788 campaign.

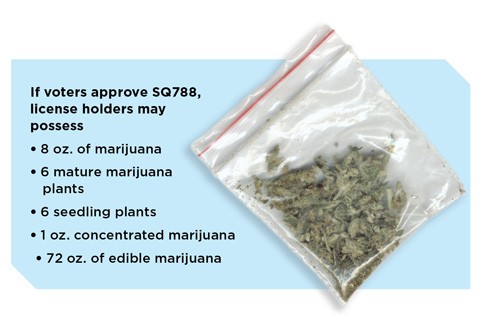

Those who cast “yes” ballots support legalizing medical marijuana in a state statue, not the state constitution. Further, a “yes” vote authorizes the state to set up a system to tax and regulate the use of medical marijuana. A “no” vote is against the measure.

Unlike some states with medical marijuana programs, SQ788 places no restrictions on conditions under which marijuana can be prescribed. The petition’s authors wanted to give physicians the “freedom to recommend as they see fit.” Oklahoma Department of Health will issue medical marijuana licenses after reviewing applications signed by physicians.

SQ788, like many of the state questions before it, comes with a companion bill, or at least a companion bill making its way through the state Capitol this legislative session. Authored by Yukon Republican Rep. John Paul Jordan, House Bill 3468 creates an independent commission, called the Cannabis Commission, to regulate medical marijuana. The legislation is endorsed by the Vote Yes on 788 campaign.

Should Oklahoma voters approve SQ788, they would activate HB3468 and the creation of the Cannabis Commission, which would oversee the medical marijuana program, including “operations relating to the issuance of licenses, the dispensing, cultivating, processing, transporting and sale of medical marijuana in Oklahoma.” The commission will be initially developed by the state Department of Health but would become its own agency on or before July 1, 2019.

“People need to understand that [SQ788] is not the end; it is the beginning of a medical marijuana program in Oklahoma,” Grove said. “It’s a program that will continue to evolve.”

Firsthand advocacy

Many businesses and entrepreneurs are currently lining up to take advantage of a possible “yes” vote on SQ788, hoping to stake out territory as growers, distributors or dispensary operators. Some began laying the foundation for their entry into a possible medical marijuana industry in Oklahoma last year, when new state legislation legalized cannabidiol (CBD).In April 2017, Gov. Mary Fallin signed House Bill 1559 into law, which amended the state’s definition of marijuana to exclude CBD, a chemical compound found in marijuana that alters neurotransmitter release but does not have any psychoactive effects. In other words, it does not get you high, but it could relieve your chronic pain.

CBD products might be how Herban Mother and owners Hector and Mary Najar make their money, but their work is motivated by far more than profit margin.

“If you ever talk to anyone that’s an advocate for the plant, we all have a story,” Hector Najar said. “If you find someone who is passionate like I am, they’re going to have a story.”

Najar owns Paseo Arts District cannabidiol (CBD) boutique Herban Mother, 607 NW 28th St. The store sells oral, topical and vapor CBD products to relieve a variety of pains and other ailments. Herban Mother began more than two years ago as a skincare company located in the Farmers Market District.

Najar, originally from San Antonio, Texas, served three combat tours in the United States Air Force. His time in the military led to degenerative disc disease and arthritis in his back and neck.

He was first exposed to the healing potential of CBD products while attending the first High Times Cannabis Cup in Southern California and was amazed how it totally relieved his pain after decades of chronic suffering.

Through the use of Herban Mother’s own products, Najar has been able to eliminate the pain he had been experiencing and has canceled scheduled surgeries.

Najar occasionally sees people coming into his shop who he can tell are in pain. They come in because they are curious or they’re buying for someone else. He asks them why they don’t use CBD to relieve their own pain, and often, he hears the response that their pain is not all that bad.

“I shake my head and say, ‘You don’t have to be in pain at all — zero; zilch,’” he said. “That’s what this is about.”

Najar believes SQ788 will pass, but he does not want anyone taking the vote for granted.

“My biggest concern is that we may have some people who get lackadaisical in their voting responsibilities,” he said. “They’ll let their next-door neighbor cover their vote, and then they wake up the next morning and guess what — we didn’t get enough votes.”

Marijuana vs. opioids

As the country experienced its largest historic increase in drug overdose deaths between 2015 and 2016, the epidemic gained national and state-level attention, much of which focused on the distribution of prescription opioids.“If Oklahoma is not ground zero, it is close,” state Attorney General Mike Hunter wrote in the introduction of the final report from the Oklahoma Commission on Opioid Abuse, noting that drug overdose deaths in Oklahoma increased 91 percent over the last 15 years.

The commission’s report released in January before the Legislative session reads like a wish list. It details a few measures, including a “Good Samaritan” law to shield a person who calls 911 for an overdose from drug possession charges; outlawing trafficking of the synthetic opioid Fentanyl; and encouraging pharmacists to offer Naloxone, which can be used to reverse an opioid overdose.

Unlike states like West Virginia ($10 million) and Tennessee ($30 million), which included state funding for treatment facilities in similar reports, Oklahoma is relying on passage of a 10 percent tax on opioid distributors and manufacturers, which likely have to survive years of court challenges by pharmaceutical companies if it can even get three-fourths approval from the Legislature. State Impact points out that seven states have not passed similar measures since 2015.

Toward the end of a press conference with Oklahoma Commission on Opioid Abuse to announce the report, Hunter was asked about the potential impact of medical marijuana as a pain-relieving alternative to opioids.

Hunter took exception to the language of the state question, which he said does not require a prescription or doctor’s validation of a condition, only that a doctor issues a license and creates a laissez-faire implementation of distribution and cultivation.

“If it is [the voter’s] intention to support a bill that is much more recreational marijuana-light, that is up to them,” Hunter said, noting that the state supreme court did not accept the AG’s re-draft of the state question.

In early April, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a pair of studies showing a correlation between a drop in opioid prescriptions for Medicaid enrollees in states that have medical or recreational marijuana laws.

“We do know that cannabis is much less risky than opiates, as far as likelihood of dependency,” University of Georgia’s W. David Bradford wrote in one study. “And certainly there’s no mortality risk [from marijuana].”

Hefei Wen of the University of Kentucky College of Public Heath wrote in a separate report that medical and recreational marijuana for adults “have the potential to reduce opioid prescribing for Medicaid enrollees, a segment of the population with disproportionately high risk for chronic pain, opioid use disorder and opioid overdose. Nevertheless, marijuana liberalization alone cannot solve the opioid epidemic.”

Bradford agrees with Wen’s findings, telling National Public Radio (NPR), “I hope nobody reading our study will say, ‘Oh, great; the answer to the opiate problem is just put cannabis in everybody’s medicine chest and we are good to go.’”